1971–72 Namibian contract workers strike

The 1971–72 Namibian contract workers strike was a labour dispute in Namibia between African contract workers (particularly miners)[4] and the apartheid government. Workers sought to end the contract labour system, which many characterised as close to slavery.[5][6] An underlying goal was the promotion of independence under SWAPO leadership.[6] It began on 13 December 1971 in Windhoek and the 14th in Walvis Bay before spreading among miners in Tsumeb and beyond. Approximately 25,000 workers participated in the strike by its end, mainly those from Ovamboland in the country's densely populated north.[7][8][6] The strike continued into the next year before ending in March 1972.

| 1971–1972 Namibian Contract Strike | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of South African Border War & Apartheid | |||

| Date | December 13, 1971[1] - March, 1972 | ||

| Location | |||

| Goals | To end the contract labour system Better working/living conditions | ||

| Resulted in | End of SWANLA contract labour New contract labour system established | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| Number | |||

| |||

| Casualties and losses | |||

Background

Historical

During this period Namibia existed under the context of Apartheid, as a subjugated colonial state of South Africa.[7] Apartheid started in 1948[9] under British control through the Union of South Africa state. By the mid-1960s around 45-50% of the Black labour force was contract migrant labour from the Namibia northern colonial reserves.[7]

The contract system existed under the control of SWANLA, a semi-governmental agency. Any Black or Indigenous person who lived within the colonial reserves were not allowed outside the boundaries of these reserves unless they signed a 12-18 month fixed labour contract with SWANLA, which offered set wage-rates & conditions with no bargaining allowed. Workers were required to carry around passes with their movement strictly controlled & monitored. Women were barred from signing and as such not allowed outside the reserves.[7]

Contract workers then would be leased out by SWANLA to other businesses. Any breaking of the contract, such as quitting or labour organising, brought criminal sanctions alongside severe disciplinary punishments that could be exercised by the employer. Contract workers also lived in compounds controlled by their employers through SWANLA.[7] As such, alongside the typically bad working conditions, it's been characterised by many as close to slavery.[5][6]

For contract work under SWANLA, workers were classified into 4 separate grades of physical fitness, and to some extent job experience: Class A, B, C, and [Child][lower-alpha 1].[7][1] Wages were monthly, with the minimum ranging from 3.75 (for a child) to 8.75 Rand (for Class A).[1] For reference, at the time this was $5 to $10 USD.[1]

The preceding decades of apartheid before the strike saw significant labour organising efforts and prevalent strikes, including the development of OPO.[7] The Windhoek or Old Location massacre occurred in 1959, which in part led to the formation of SWAPO[10][7] from OPO. This played a large role in the fight against apartheid within Namibia, including a limited role within this strike.

Immediate

In August 1971, pro-independence students, many of which already had experience with contract work, were expelled from high schools throughout Ovamboland by South African officials. Many former students then took contract work with the intention of promoting a general strike.[7] They cooperated with local workers and SWAPO branches to establish contact with others to kickstart the campaign.

Previous organising had already established a substantial degree of autonomy within the big compounds. Alongside this, tactics used to subvert pass laws allowed significant mobilisation within these compounds. Police responded with mass raids, where all workers were searched systematically and wide arrests were made.[7]

In March & June, Katutura, Windhoek was raided by police and a checkpoint was established at it's only entrance where workers were forced to show valid passes, disrupting pass evasion. Five months later on the night of November 11th, workers raided the checkpoint and offices, destroying them. Police responded with another large raid four days later.[7]

In June, the International Court of Justice ruled that South Africa's ongoing occupation of Namibia was illegal, which was used to encourage anti-colonial actions within the territory.[5]

By early November, labour organising had enough ground to organise more openly. Organisers at Walvis Bay called a mass meeting attended by the majority of contract workers in the compound. During this meeting a deadline was established for the start of the strike, with letters & information sent out to other compounds. It was decided there that mass meetings would be held on Sunday, December 12th at both Walvis Bay & Windhoek, and that the strike would start the following week. With the information reaching Windhoek on December 5th.[7]

Given the pass system, workers planned to return to the Ovamboland reserve for the span of the strike. This was in part a response to the statements of Jan de Wet, the Commissioner General for Ovamboland, made earlier on when the government became aware of a potential strike. He claimed contract labour was not slavery since workers signed the contracts. In reality the economic conditions within the reserves in conjunction with the pass system often forced signing them as a means of survival.[7] Special taxation of those in the reserves by the South African government also worsened this, which some claim was by design.[1]

In a letter written on November 28, as a culmination of the earlier mass meeting, workers at Windhoek wrote in response[7]:

...He said we ourselves want to be on contract because we come to work. We must talk about ending the system. We in Walvis Bay discussed it. We wrote a letter to the government of Ovamboland and to SWANLA. We will not come back. We will leave Walvis Bay and the contract, and will stay at home as the Boer J. de Wet said.

In response to the earlier November meeting, police arrested 14 organisers at Walvis Bay. The meeting also revealed some of the leadership and the timing of the strike to the South African government. Which likely played a role in the mitigated success of the strike in Walvis Bay compared to Windhoek.[7]

On December 12th[7][1] during the planned mass meeting at Walvis Bay (which also occurred at Windhoek) the South African government led a strike opposition meeting with pro-government speakers & Bantustan officials. This action however backfired due to the militant response of workers, with Bishop Auala, the influential head figure of ELOK, being persuaded to endorse the strike during it.

Course of the strike

The strike started on the December 13th in Windhoek and the 14th in Walvis Bay, both large workers compounds.[7][1]

In Windhoek, workers boycotted the food prepared in the compound kitchens on the first day of its strike. Moving in and out of the compound to buy food at local shops. The next day on the 14th police sealed off the compound, locking workers inside.[1] Similarly the Walvis Bay compound was sealed off premptively by police on the same day, the very first day of it's strike.[7]

By December 20th, 11,500 workers had come out for the strike. By mid-January 18,000 workers had returned to Ovamboland, of them 13,500 of the workers transported by rail by the government who wanted to avoid the conflict occurring at compounds which were in the centers of production and also closer to white residences.[7]

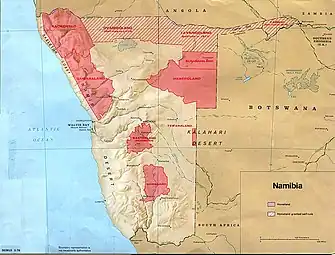

In total 25,000 workers were involved in the strike: 22,500 from towns, mines & camps. More then half of the 43,400 people within the Police Zone.[11][7] The Police Zone during this time was an area within South West Africa (now Namibia) where Indigenous people were not allowed to enter unless they were on a labour contract.

It was originally established in 1905[12] when South West Africa was a German colony, before the contract system was established. It's direct cause was the 1897 rinderpest epidemic which led to massive cattle die-offs, an estimated 95% of cattle in southern & central Namibia.[12] During it a veterinary cordon fence was established. The epidemic made policing borders (in order to prevent disease from being spread to healthy cattle) required for any colonial benefit to Germany, effectively exposing the fragility of their colonial control.[12] The fences limits were practically defined by the areas Germany feasibly had control over and could police the borders of. In 1905, the resolution to form the Police Zone was passed in Berlin. Stating the new zone "should be restricted to the smallest possible area... [focusing] where our economic interests tend to coalesce".[13] The boundary for the Police Zone ended up being broadly defined by the veterinary cordon fence established earlier.[12]

This became a significant policed boundary between the white German colonizers and the Indigenous population within Namibia. Setting one of the foundations for what would later become racial apartheid in the 1940s.[12]

Alongside those within the Police Zone striking, over 70% of those employed outside the Police Zone had joined the strike against the contract system. One action that accelerated and expanded the strike was by the South African government. On government controlled radio they criticized the workers that had left for the Ovamboland reserve. When workers outside the compounds heard this news, many of them joined the strike they were previously unaware of.[7]

During the strike an ad hoc strike committee was formed by workers in Ovamboland with members elected on a regional basis. They met on January 3rd and decided to reject any agreement not supported by the strikers, they also drew up lists of miner specific grievances & demands, and held a mass meeting a week later. At this meeting a deputation was elected to represent the worker at upcoming negotiations with the government, the major employers and Bantustan executive from January 19-20th at Grootfontein.[7]

While the strike continued, pickets were held at the borders which successfully turned back potential labour migrants that otherwise would act as strikebreakers.[7] The strike goals also widened to include the grievances of not just workers but the general Indigenous peoples within the reserves. Becoming a more general resistance against apartheid and colonialism that brought more active confrontations. During this the government briefly stoned off roads north of Ondangwa.[7]

On the night of January 16th, over 100km of border fences were destroyed by those with grievances against the apartheid government and in the following weeks a series of attacks were made on stock control posts, inspectors, headmen and informers. This happened on both sides of the borders. The most radical resistance was concentrated within Ulwanyama along the border.[7]

An agreement was released on January 20, 1972, which abolished the South West Africa Native Labour Association (SWANLA), required written employment contracts with details of entitlements and conditions, removed criminal sanctions but added civil sanctions against workers deemed to have breached employment contracts and established some mechanisms to resolve disputes.[14] However, in practical terms not much changed for contract workers.[7][15] After this agreement some workers returned,[7][16] however the strike did not fully end with many continuing to strike.[7][4] Severe police repression and attacks also continued to be carried out against any workers trying to meet.[7]

Ondobe and Epinga massacres

On January 28, 1972, three men were killed by police at Ondobe.[2] Later on January 30, 1972, five workers were shot and killed by police in the Epinga village.[2]

A mass grave of the 5 contract workers became known by the broader public in 2008, buried miles away.[3] Four of the workers died in the village (Thomas Mueshihange, Benjamin Herman, Lukas Veiko and Mathias Ohainenga). While three others were injured but survived and another died later in the hospital (Ngesea Sinana).[2]

Breaking of the strike

By late February the strike had been partially broken. However, wide scale opposition continued, eventually merging into a long-term guerilla campaign in the north as a part of the Namibian War of Independence. For the strike, many workers continued to hold out, with some but not all of them returning many months later.[7] Some accounts, note March, 1972.[17] While one (from SWAPO member John Ya-Otto) claims May, 1972.[18]

Aftermath

According to one South African Journal, contract labour continued until it was banned in 1977 through the General Law Amendment Proclamation, AG 5 of 1977.[19] This coincided with the escalation of the South African Border War from the new South African prime minister P. W. Botha in 1979.[20]

The banning of contract labour stayed until it reemerged in the 1990s inside Namibia, in the form of the labour hire system.[19] There have been attempts to re-abolish it such as the Namibian Labour Act of 2007, but this was reversed by the courts system in December, 2009 before it could be implemented.[19][21]

"[91] For these reasons, the prohibition of the economic activity defined by s. 128(1) in its current form is so substantially overbroad that it does not constitute a reasonable restriction on the exercise of the fundamental freedom to carry on any trade or business protected in Article 21(1)(j) of the Constitution and, on that basis alone, the section must be struck down as unconstitutional."[21] (bolding added)

The court decision was only a few months after the act was to officially go into effect on March 1, 2009.[22] However, in practice the law was never implemented as its legal power was suspended on February 27 till the court decision finished.[23] Labour hire has since been partially regulated through the Labour Amendment Act 2 of 2012 which provides some minimal labour protections in the face of the 2007 law being removed.[19]

See also

Notes

- The SWANLA classification used a derogatory term for Black children, Piccanin

References

- Hayes, Steve (1971-12-24), The Strike of Ovambo Workers in South West Africa and the Churches, retrieved 2023-04-02

- J. Temu, Arnold; das N. Tembe, Joel (eds.). "Southern African Liberation Struggles:1960–1994 Contemporaneous Documents" (PDF). SADC Hashim Mbita Project. 3: 155–160.

- Namibian, The. "Police knew of 1972 mass grave: Minister". The Namibian. Retrieved 2023-03-30.

- "South Africa Flies Extra Policemen to Area of Strike by 13,000 Black Miners". The New York Times. 13 January 1972.

- "Ovambo migrant workers general strike for rights, Namibia, 1971–72". Global Nonviolent Action Database.

- Rogers, Barbara (1972). "Namibia's General Strike". Africa Today. 19 (2): 3–8. ISSN 0001-9887.

- Moorsom, Richard (April 1979). "Labour Consciousness and the 1971–72 Contract Workers Strike in Namibia". Development and Change. 10 (2): 205–231. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.1979.tb00041.x.

- Jauch, Herbert (2018). "Namibia's Labour Movement: An Overview

History, Challenges and Achievements" (PDF). Friedrich Ebert Foundation. - Kenney, Henry (2016). Verwoerd: Architect of Apartheid. Jonathan Ball Publishers. ISBN 978-1-86842-716-1.

- Dierks, Dr. Klaus (January 2005). "Chronology Of Namibian History: From Pre-historical Times to Independent Namibia/December 2000". www.klausdierks.com. Retrieved 2023-05-13.

- "Police Zone | historical area, Namibia | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-05-15.

- Lechler, Marie; McNamee, Lachlan (December 2018). "Indirect Colonial Rule Undermines Support for Democracy: Evidence From a Natural Experiment in Namibia" (PDF). Comparative Political Studies. 51 (14): 1864–1871 (p. 7-14). doi:10.1177/0010414018758760. ISSN 0010-4140. Archived from the original on 2023.

- Lechler, Marie; McNamee, Lachlan (December 2018). "Indirect Colonial Rule Undermines Support for Democracy: Evidence From a Natural Experiment in Namibia" (PDF). Comparative Political Studies. 51 (14): 1865 (p. 8). doi:10.1177/0010414018758760. ISSN 0010-4140. Archived from the original on 2023.

- Kooy, Marcelle (1973). "The Contract Labour System and the Ovambo Crisis of 1971 in South West Africa". African Studies Review. 16 (1): 83–105. doi:10.2307/523735. JSTOR 523735. S2CID 153855067.

- Melber, Henning (1983). "The National Union of Namibian Workers: Background and Formation". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 21 (1): 151–158. ISSN 0022-278X.

- "Newmont Says Strike Ends at African Mine held by U.S. Interests: Ovambo Tribesmen Walked Out Dec. 17 to Fight Government's Fixed 18-Month Labor System". Wall Street Journal. 31 January 1972. p. 16. ProQuest 133665044.

- H. Katjavivi, Peter (1990). "A History of Resistance in Namibia". South African History Online. p. 77 (p. 70). Retrieved 2023-05-17.

- Ya-Otto, John (1981). Battlefront Namibia : an autobiography. Internet Archive. Westport, Ct : L. Hill & Co. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-88208-132-8.

- Botes, Anri (26 April 2017). "The History of Labour Hire in Namibia: A Lesson for South Africa". Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal. 16 (1): 505–536. doi:10.17159/1727-3781/2013/V16I1A2320. SSRN 2263142.

- Jaster, Robert Scott (1989). "Growing Militancy and Isolation under P.W. Botha since 1978". The Defence of White Power. pp. 79–91. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-19601-2_6. ISBN 978-1-349-19603-6.

- "Africa Personnel Services (Pty) Ltd v Government of Republic of Namibia and Others (SA 51/2008) [2009] NASC 17; [2011] 1 BLLR 15 (NmS) ; (2011) 32 ILJ 205 (Nms) (14 December 2009)". namibialii.org. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- "Labour Act 11 of 2007" (PDF). Republic of Namibia.

- "Namibian Supreme Court Strikes Down Labour Hire Bill". IndustriALL. 2010-01-11. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

.png.webp)