Askold and Dir

Askold and Dir (Haskuldr or Hǫskuldr and Dyr or Djur in Old Norse; died in 882), mentioned in both the Primary Chronicle[1] the Novgorod First Chronicle[2] and the Nikon Chronicle,[3] were the earliest known purportedly Norse rulers of Kiev.[4]

Primary Chronicle and Novgorod First Chronicle

The Laurentian Codex of the Primary Chronicle relates that Askold and Dir were sanctioned by Rurik to go to Constantinople (Norse Miklagård, Slavic Tsargrad). When travelling on the Dnieper, they settled in Kiev seizing power over the Polans who had been paying tribute to the Khazars. The chronicle also states that they were killed by Oleg the Wise in 882.[1] According to the Primary Chronicle, Oleg came to the foot of the Hungarian hill using trickery, as after concealing his troops in a boat, he sent messengers to Askold and Dir, representing himself as a stranger on his way to Greece on an errand for Oleg and for Igor', the prince's son, and requesting that they should come forth to greet them as members of their race, and killed them with soldiers hidden in the boats popping out, saying Askold and Dir is not worthy of ruling the city since they are not of princely birth.[5] Vasily Tatishchev, Boris Rybakov and some other Russian and Ukrainian historians interpreted the 882 coup d'état in Kiev as the reaction of the pagan Varangians to Askold's baptism. Tatishchev went so far as to style Askold "the first Rus' martyr".[6] Igor was still "very young", and Oleg was "carrying" him to Kiev.[2]

In the Novgorod First Chronicle, it was not Oleg, but Igor who initiated the actions: telling Askold that he, unlike Igor himself, was not a prince or of a princely clan, Igor and his soldiers killed Askold and Dir, and then Igor rather than Oleg became prince in Kiev.[2] Igor went on to impose tributes on various tribes, and brought himself a wife named Olga from Pleskov (Pskov), with whom he had a son called Sviatoslav.[7] Ostrowski (2018) noted that this is rather different from the narrative in the Primary Chronicle, where Oleg is in charge while Igor is passive and not mentioned again until 23 later: "As Igor’ grew up, he followed after Oleg, and obeyed his instructions", and Olga "was brought to him from Pskov" to be his bride.[8] In the subsequent Rusʹ–Byzantine War (907) (absent in Byzantine sources), the Novgorod First Chronicle again narrates that it was Igor leading the attack (Old East Slavic: Посла князь Игорь на ГрЂкы вои В Русь скыдеи тысящь.[7] "Prince Igor went against the Greeks with thousands of Rus' warriors."), yet the Primary Chronicle once more claims: "Oleg went against the Greeks, leaving Igor’ in Kiev."[8]

| Act | Novgorod First Chronicle (NPL) | Laurentian Codex (Lav) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old East Slavic | Modern English | Old East Slavic | Modern English | |

| Lineage 23:14–16 |

и рече Игорь ко Асколду: "вы нЂста князя, ни роду княжа, нь азъ есмь князь, и мнЂ достоить княжити".[7] | And Igor said to Askold: "Thou art not a prince, nor of a clan of princes, but I am a prince, and I am worthy to reign as prince."[7][9] | и рече ѡлегъ асколду и дирови. вы нѣста кнѧзѧ. ни рода кнѧжа. но азъ есмь. роду кнѧжа.[10][8] | and Oleg said to Askold and Dir, "You are not princes nor even of princely stock, but I am of princely birth."[11] |

| Killing 23:17–18 |

И убиша Асколда и Дира; и абие несъше на гору, и погребоша и Асколда на горЂ[7] | And they killed Askold and Dir; and he was taken to the mountain, and Askold was buried on the mountain[7] | И убиша Асколда и Дира, несоша на гору и погребша и на горѣ.[12] | And they killed Askold and Dir, and after carrying them to the hill, they buried them there[11] |

| Prince in Kyev 23:22–23 |

И сЂде Игорь, княжа, в КыевЂ.[7] | And Igor, the prince, went to Kyevđ.[7] | сѣде ѡлегъ кнѧжа въ киевѣ. и реч ѡлегъ се буди м҃ти градомъ руским и. | Oleg set himself up as prince in Kyiv, and declared that it should be the mother of Rus' cities.[11] |

Al-Masudi

The only foreign source to mention one of the co-rulers is the Arab historian Al-Masudi. According to him, "king al-Dir [Dayr] was the first among the kings of the Slavs." Although some scholars have tried to prove that "al-Dir" refers to a Slavic ruler and Dir's contemporary, this speculation is questionable and it is at least equally probable that "al-Dir" and Dir were the same person.[13]

Facts and records

The Rus' attack on Constantinople in June 860 took the Greeks by surprise, "like a thunderbolt from heaven," as it was put by Patriarch Photios in his famous oration written for the occasion. Although the Slavonic chronicles tend to associate this expedition with the names of Askold and Dir (and to date it to 866), the connection remains tenuous. Despite Photius' own assertion that he sent a bishop to the land of Rus' which became Christianized and friendly to Byzantium, most historians discard the idea of Askold's subsequent conversion as apocryphal.

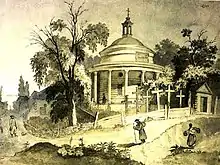

A Kievan legend identifies Askold's burial mound with Uhorska Hill, where Olga of Kiev later built two churches, devoted to Saint Nicholas and to Saint Irene. Today this place on the steep bank of the Dnieper is marked by a monument called Askold's Grave.

Legacy

- Russian screw frigate Askold (1854) (see List of Russian steam frigates)

- Russian cruiser Askold (1900)

- Askold's Grave(19th century Russian Opera by Alexey)

See also

References

- Nestor; Cross, Samuel H; Sherbowitz-Wetzor, Olgerd P (1953). The Russian Primary chronicle (PDF). Cambridge, Mass.: Mediaeval Academy of America. pp. 60–61. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-10-16. Retrieved 2022-03-11.

- Ostrowski 2018, p. 39–40.

- Zenkovsky, Serge A.; Zenkovsky, Betty Jean (1984). The Nikonian Chronicle: From the beginning to the year 1132. Kingston Press. pp. 16–29. ISBN 978-0-940670-00-6.

- Zakharii, Roman (2002). "The historiography of Normanist and anti-Normanist theories on the origins of Rus' : a review of modern historiography and major sources on Varangian controversy and other Scandinavian concepts of the origins of Rus'".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Many scholars believe the conquest of Kiev took place a generation later; see Oleg of Novgorod for discussion of the controversy surrounding this date.

- The Ukrainian Review. Vol. 10. Association of Ukrainians in Great Britain. 1962. p. 47.

- Izbornyk 2001.

- Ostrowski 2018, p. 40.

- Ostrowski 2018, p. 39.

- Ostrowski & Birnbaum 2014, 23, 14–16.

- Cross & Sherbowitz-Wetzor 2013, p. 8.

- Ostrowski & Birnbaum 2014, 23, 17–18.

- Golden, P.B. (2006) "Rus." Encyclopaedia of Islam (Brill Online). Eds.: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill.

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Cross, Samuel Hazzard; Sherbowitz-Wetzor, Olgerd P. (1930). The Russian Primary Chronicle, Laurentian Text. Translated and edited by Samuel Hazzard Cross and Olgerd P. Sherbowitz-Wetzor (1930) (PDF). Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Mediaeval Academy of America. p. 325. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- Cross, Samuel Hazzard; Sherbowitz-Wetzor, Olgerd P. (2013) [1953]. SLA 218. Ukrainian Literature and Culture. Excerpts from The Rus' Primary Chronicle (Povest vremennykh let, PVL) (PDF). Toronto: Electronic Library of Ukrainian Literature, University of Toronto. p. 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2014. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- Ostrowski, Donald; Birnbaum, David J. (7 December 2014). "Rus' primary chronicle critical edition – Interlinear line-level collation". pvl.obdurodon.org. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- Izbornyk (2001). "Новгородская Первая Летопись Младшего Извода" [Novgorod First Chronicle of the Younger Edition]. Izbornyk (in Church Slavic). Retrieved 15 May 2023.

Literature

- Dimnik, Martin (January 2004). "The Title "Grand Prince" in Kievan Rus'". Mediaeval Studies. 66: 253–312. doi:10.1484/J.MS.2.306512. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- Ostrowski, Donald (2018). "Was There a Riurikid Dynasty in Early Rus'?". Canadian-American Slavic Studies. 52 (1): 30–49. doi:10.1163/22102396-05201009.

External links

- Guide to Askold's Grave

- Yasterbov, O. The reign of the princes Askold and Dyr: beginnings of the mighty Kyivan state. Day. 29 November 2005. (in English)