Lemniscate elliptic functions

In mathematics, the lemniscate elliptic functions are elliptic functions related to the arc length of the lemniscate of Bernoulli. They were first studied by Giulio Fagnano in 1718 and later by Leonhard Euler and Carl Friedrich Gauss, among others.[1]

The lemniscate sine and lemniscate cosine functions, usually written with the symbols sl and cl (sometimes the symbols sinlem and coslem or sin lemn and cos lemn are used instead),[2] are analogous to the trigonometric functions sine and cosine. While the trigonometric sine relates the arc length to the chord length in a unit-diameter circle [3] the lemniscate sine relates the arc length to the chord length of a lemniscate

The lemniscate functions have periods related to a number 2.622057... called the lemniscate constant, the ratio of a lemniscate's perimeter to its diameter. This number is a quartic analog of the (quadratic) 3.141592..., ratio of perimeter to diameter of a circle.

As complex functions, sl and cl have a square period lattice (a multiple of the Gaussian integers) with fundamental periods [4] and are a special case of two Jacobi elliptic functions on that lattice, .

Similarly, the hyperbolic lemniscate sine slh and hyperbolic lemniscate cosine clh have a square period lattice with fundamental periods

The lemniscate functions and the hyperbolic lemniscate functions are related to the Weierstrass elliptic function .

Lemniscate sine and cosine functions

Definitions

The lemniscate functions sl and cl can be defined as the solution to the initial value problem:[5]

or equivalently as the inverses of an elliptic integral, the Schwarz–Christoffel map from the complex unit disk to a square with corners [6]

Beyond that square, the functions can be analytically continued to the whole complex plane by a series of reflections.

By comparison, the circular sine and cosine can be defined as the solution to the initial value problem:

or as inverses of a map from the upper half-plane to a half-infinite strip with real part between and positive imaginary part:

Arc length of Bernoulli's lemniscate

The lemniscate of Bernoulli with half-width 1 is the locus of points in the plane such that the product of their distances from the two focal points and is the constant . This is a quartic curve satisfying the polar equation or the Cartesian equation

The points on the lemniscate at distance from the origin are the intersections of the circle and the hyperbola . The intersection in the positive quadrant has Cartesian coordinates:

Using this parametrization with for a quarter of the lemniscate, the arc length from the origin to a point is:[7]

Likewise, the arc length from to is:

Or in the inverse direction, the lemniscate sine and cosine functions give the distance from the origin as functions of arc length from the origin and the point , respectively.

Analogously, the circular sine and cosine functions relate the chord length to the arc length for the unit diameter circle with polar equation or Cartesian equation using the same argument above but with the parametrization:

Alternatively, just as the unit circle is parametrized in terms of the arc length from the point by

the lemniscate is parametrized in terms of the arc length from the point by[8]

The lemniscate integral and lemniscate functions satisfy an argument duplication identity discovered by Fagnano in 1718:[9]

Later mathematicians generalized this result. Analogously to the constructible polygons in the circle, the lemniscate can be divided into n sections of equal arc length using only straightedge and compass if and only if n is of the form where k is a non-negative integer and each pi (if any) is a distinct Fermat prime.[10] The "if" part of the theorem was proved by Niels Abel in 1827–1828, and the "only if" part was proved by Michael Rosen in 1981.[11] Equivalently, the lemniscate can be divided into n sections of equal arc length using only straightedge and compass if and only if is a power of two (where is Euler's totient function). The lemniscate is not assumed to be already drawn; the theorem refers to constructing the division points only.

Let . Then the n-division points for the lemniscate are the points

where is the floor function. See below for some specific values of .

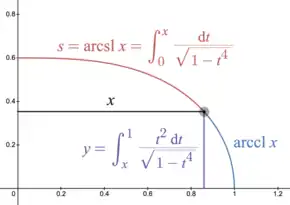

Arc length of rectangular elastica

The inverse lemniscate sine also describes the arc length s relative to the x coordinate of the rectangular elastica.[12] This curve has y coordinate and arc length:

The rectangular elastica solves a problem posed by Jacob Bernoulli, in 1691, to describe the shape of an idealized flexible rod fixed in a vertical orientation at the bottom end and pulled down by a weight from the far end until it has been bent horizontal. Bernoulli's proposed solution established Euler–Bernoulli beam theory, further developed by Euler in the 18th century.

Elliptic characterization

Let be a point on the ellipse in the first quadrant and let be the projection of on the unit circle . The distance between the origin and the point is a function of (the angle where ; equivalently the length of the circular arc ). The parameter is given by

If is the projection of on the x-axis and if is the projection of on the x-axis, then the lemniscate elliptic functions are given by

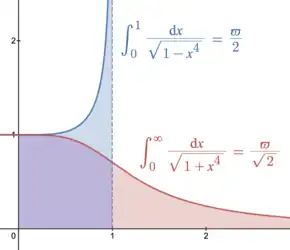

Relation to the lemniscate constant

The lemniscate functions have minimal real period 2ϖ[13] and fundamental complex periods and for a constant ϖ called the lemniscate constant,[14]

The lemniscate functions satisfy the basic relation analogous to the relation

The lemniscate constant ϖ is a close analog of the circle constant π, and many identities involving π have analogues involving ϖ, as identities involving the trigonometric functions have analogues involving the lemniscate functions. For example, Viète's formula for π can be written:

An analogous formula for ϖ is:[15]

The Machin formula for π is and several similar formulas for π can be developed using trigonometric angle sum identities, e.g. Euler's formula . Analogous formulas can be developed for ϖ, including the following found by Gauss: [16]

The lemniscate and circle constants were found by Gauss to be related to each-other by the arithmetic-geometric mean M:[17]

Zeros, poles and symmetries

The lemniscate functions cl and sl are even and odd functions, respectively,

At translations of cl and sl are exchanged, and at translations of they are additionally rotated and reciprocated:[19]

Doubling these to translations by a unit-Gaussian-integer multiple of (that is, or ), negates each function, an involution:

As a result, both functions are invariant under translation by an even-Gaussian-integer multiple of .[20] That is, a displacement with for integers a, b, and k.

This makes them elliptic functions (doubly periodic meromorphic functions in the complex plane) with a diagonal square period lattice of fundamental periods and .[21] Elliptic functions with a square period lattice are more symmetrical than arbitrary elliptic functions, following the symmetries of the square.

Reflections and quarter-turn rotations of lemniscate function arguments have simple expressions:

The sl function has simple zeros at Gaussian integer multiples of ϖ, complex numbers of the form for integers a and b. It has simple poles at Gaussian half-integer multiples of ϖ, complex numbers of the form , with residues . The cl function is reflected and offset from the sl function, . It has zeros for arguments and poles for arguments with residues

Also

for some and

The last formula is a special case of complex multiplication. Analogous formulas can be given for where is any Gaussian integer – the function has complex multiplication by .[22]

There are also infinite series reflecting the distribution of the zeros and poles of sl:[23][24]

The lemniscate functions as a ratio of entire functions

Since the lemniscate sine is a meromorphic function in the whole complex plane, it can be written as a ratio of entire functions. Gauss showed that sl has the following product expansion, reflecting the distribution of its zeros and poles:[25]

where

Here, and denote, respectively, the zeros and poles of sl which are in the quadrant . Gauss conjectured that (this later turned out to be true) and commented that this “is most remarkable and a proof of this property promises the most serious increase in analysis”.[26] Gauss expanded the products for and as infinite series. He also discovered several identities involving the functions and , such as

and

Since the functions and are entire, their power series expansions converge everywhere in the complex plane:[27][28][29]

Analogously, the lemniscate cosine can be written as

where[30]

Furthermore,

and the Pythagorean-like identities

for .

An alternative way of expressing the lemniscate functions as a ratio of entire functions involves the theta functions (see Lemniscate elliptic functions § Methods of computation; the theta functions and the above functions are not equivalent).

Pythagorean-like identity

_%253D_a(1_-_x%C2%B2y%C2%B2)_for_various_values_of_a.png.webp)

The lemniscate functions satisfy a Pythagorean-like identity:

As a result, the parametric equation parametrizes the quartic curve

This identity can alternately be rewritten:[31]

Defining a tangent-sum operator as gives:

The functions and satisfy another Pythagorean-like identity:

Derivatives and integrals

The derivatives are as follows:

The second derivatives of lemniscate sine and lemniscate cosine are their negative duplicated cubes:

The lemniscate functions can be integrated using the inverse tangent function:

Argument sum and multiple identities

Like the trigonometric functions, the lemniscate functions satisfy argument sum and difference identities. The original identity used by Fagnano for bisection of the lemniscate was:[32]

The derivative and Pythagorean-like identities can be used to rework the identity used by Fagano in terms of sl and cl. Defining a tangent-sum operator and tangent-difference operator the argument sum and difference identities can be expressed as:[33]

These resemble their trigonometric analogs:

In particular, to compute the complex-valued functions in real components,

Bisection formulas:

Duplication formulas:[34]

Triplication formulas:[34]

Note the "reverse symmetry" of the coefficients of numerator and denominator of . This phenomenon can be observed in multiplication formulas for where whenever and is odd.[22]

Lemnatomic polynomials

Let be the lattice

Furthermore, let , , , , (where ), be odd, be odd, and . Then

for some coprime polynomials and some [35] where

and

where is any -torsion generator (i.e. and generates as an -module). Examples of -torsion generators include and . The polynomial is called the -th lemnatomic polynomial. It is monic and is irreducible over . The lemnatomic polynomials are the "lemniscate analogs" of the cyclotomic polynomials,[36]

The -th lemnatomic polynomial is the minimal polynomial of in . For convenience, let and . So for example, the minimal polynomial of (and also of ) in is

and[37]

(an equivalent expression is given in the table below). Another example is[36]

which is the minimal polynomial of (and also of ) in

If is prime and is positive and odd,[39] then[40]

which can be compared to the cyclotomic analog

Specific values

Just as for the trigonometric functions, values of the lemniscate functions can be computed for divisions of the lemniscate into n parts of equal length, using only basic arithmetic and square roots, if and only if n is of the form where k is a non-negative integer and each pi (if any) is a distinct Fermat prime.[41] The expressions become unwieldy as n grows. Below are the expressions for dividing the lemniscate into n parts of equal length for some n ≤ 20.

| [38] | |||

Power series

The power series expansion of the lemniscate sine at the origin is[42]

where the coefficients are determined as follows:

where stands for all three-term compositions of . For example, to evaluate , it can be seen that there are only six compositions of that give a nonzero contribution to the sum: and , so

The expansion can be equivalently written as[43]

where

The power series expansion of at the origin is

where if is even and[44]

if is odd.

The expansion can be equivalently written as[45]

where

For the lemniscate cosine,[46]

where

Relation to Weierstrass and Jacobi elliptic functions

The lemniscate functions are closely related to the Weierstrass elliptic function (the "lemniscatic case"), with invariants g2 = 1 and g3 = 0. This lattice has fundamental periods and . The associated constants of the Weierstrass function are

The related case of a Weierstrass elliptic function with g2 = a, g3 = 0 may be handled by a scaling transformation. However, this may involve complex numbers. If it is desired to remain within real numbers, there are two cases to consider: a > 0 and a < 0. The period parallelogram is either a square or a rhombus. The Weierstrass elliptic function is called the "pseudolemniscatic case".[47]

The square of the lemniscate sine can be represented as

where the second and third argument of denote the lattice invariants g2 and g3. Another representation is

where the second argument of denotes the period ratio .[48] The lemniscate sine is a rational function in the Weierstrass elliptic function and its derivative:[49]

where the second and third argument of denote the lattice invariants g2 and g3. In terms of the period ratio , this becomes

The lemniscate functions can also be written in terms of Jacobi elliptic functions. The Jacobi elliptic functions and with positive real elliptic modulus have an "upright" rectangular lattice aligned with real and imaginary axes. Alternately, the functions and with modulus i (and and with modulus ) have a square period lattice rotated 1/8 turn.[50][51]

where the second arguments denote the elliptic modulus .

The functions and can also be expressed in terms of Jacobi elliptic functions:

Relation to the modular lambda function

The lemniscate sine can be used for the computation of values of the modular lambda function:

For example:

Ramanujan's cos/cosh identity

Ramanujan's famous cos/cosh identity states that if

then[44]

There is a close relation between the lemniscate functions and . Indeed,[44][52]

and

Methods of computation

A fast algorithm, returning approximations to (which get closer to with increasing ), is the following:[54]

- for each do

- if then

- for each n from N to 0 do

- return

This is effectively using the arithmetic-geometric mean and is based on Landen's transformations.[55]

Several methods of computing involve first making the change of variables and then computing

A hyperbolic series method:[56][57][58]

Fourier series method:[59]

The lemniscate functions can be computed more rapidly by

where

are the Jacobi theta functions.[60]

Two other fast computation methods use the following sum and product series:

where

Fourier series for the logarithm of the lemniscate sine:

The following series identities were discovered by Ramanujan:[61]

The functions and analogous to and on the unit circle have the following Fourier and hyperbolic series expansions:[44][52][62]

Inverse functions

The inverse function of the lemniscate sine is the lemniscate arcsine, defined as

It can also be represented by the hypergeometric function:

The inverse function of the lemniscate cosine is the lemniscate arccosine. This function is defined by following expression:

For x in the interval , and

For the halving of the lemniscate arc length these formulas are valid:

Expression using elliptic integrals

The lemniscate arcsine and the lemniscate arccosine can also be expressed by the Legendre-Form:

These functions can be displayed directly by using the incomplete elliptic integral of the first kind:

The arc lengths of the lemniscate can also be expressed by only using the arc lengths of ellipses (calculated by elliptic integrals of the second kind):

The lemniscate arccosine has this expression:

Use in integration

The lemniscate arcsine can be used to integrate many functions. Here is a list of important integrals (the constants of integration are omitted):

Hyperbolic lemniscate functions

For convenience, let . is the "squircular" analog of (see below). The decimal expansion of (i.e. [63]) appears in entry 34e of chapter 11 of Ramanujan's second notebook.[64]

The hyperbolic lemniscate sine (slh) and cosine (clh) can be defined as inverses of elliptic integrals as follows:

where in , is in the square with corners . Beyond that square, the functions can be analytically continued to meromorphic functions in the whole complex plane.

The complete integral has the value:

Therefore, the two defined functions have following relation to each other:

The product of hyperbolic lemniscate sine and hyperbolic lemniscate cosine is equal to one:

The functions and have a square period lattice with fundamental periods .

The hyperbolic lemniscate functions can be expressed in terms of lemniscate sine and lemniscate cosine:

But there is also a relation to the Jacobi elliptic functions with the elliptic modulus one by square root of two:

The hyperbolic lemniscate sine has following imaginary relation to the lemniscate sine:

This is analogous to the relationship between hyperbolic and trigonometric sine:

In a quartic Fermat curve (sometimes called a squircle) the hyperbolic lemniscate sine and cosine are analogous to the tangent and cotangent functions in a unit circle (the quadratic Fermat curve). If the origin and a point on the curve are connected to each other by a line L, the hyperbolic lemniscate sine of twice the enclosed area between this line and the x-axis is the y-coordinate of the intersection of L with the line .[66] Just as is the area enclosed by the circle , the area enclosed by the squircle is . Moreover,

where is the arithmetic–geometric mean.

The hyperbolic lemniscate sine satisfies the argument addition identity:

When is real, the derivative can be expressed in this way:

Number theory

In algebraic number theory, every finite abelian extension of the Gaussian rationals is a subfield of for some positive integer .[36][67] This is analogous to the Kronecker–Weber theorem for the rational numbers which is based on division of the circle – in particular, every finite abelian extension of is a subfield of for some positive integer . Both are special cases of Kronecker's Jugendtraum, which became Hilbert's twelfth problem.

The field (for positive odd ) is the extension of generated by the - and -coordinates of the -torsion points on the elliptic curve .[67]

Hurwitz numbers

The Bernoulli numbers can be defined by

and appear in

where is the Riemann zeta function.

The Hurwitz numbers named after Adolf Hurwitz, are the "lemniscate analogs" of the Bernoulli numbers. They can be defined by[68][69]

where is the Weierstrass zeta function with lattice invariants and . They appear in

where are the Gaussian integers and are the Eisenstein series of weight , and in

The Hurwitz numbers can also be determined as follows: ,

and if is not a multiple of .[70] This yields[68]

Also[71]

where such that just as

where (by the von Staudt–Clausen theorem).

In fact, the von Staudt–Clausen theorem states that

(sequence A000146 in the OEIS) where is any prime, and an analogous theorem holds for the Hurwitz numbers: suppose that is odd, is even, is a prime such that , (see Fermat's theorem on sums of two squares) and . Then for any given , is uniquely determined and[68]

The sequence of the integers starts with [68]

Let . If is a prime, then . If is not a prime, then .[72]

Some authors instead define the Hurwitz numbers as .

Appearances in Laurent series

The Hurwitz numbers appear in several Laurent series expansions related to the lemniscate functions:[73]

Analogously, in terms of the Bernoulli numbers:

World map projections

The Peirce quincuncial projection, designed by Charles Sanders Peirce of the US Coast Survey in the 1870s, is a world map projection based on the inverse lemniscate sine of stereographically projected points (treated as complex numbers).[74]

When lines of constant real or imaginary part are projected onto the complex plane via the hyperbolic lemniscate sine, and thence stereographically projected onto the sphere (see Riemann sphere), the resulting curves are spherical conics, the spherical analog of planar ellipses and hyperbolas.[75] Thus the lemniscate functions (and more generally, the Jacobi elliptic functions) provide a parametrization for spherical conics.

A conformal map projection from the globe onto the 6 square faces of a cube can also be defined using the lemniscate functions.[76] Because many partial differential equations can be effectively solved by conformal mapping, this map from sphere to cube is convenient for atmospheric modeling.[77]

See also

Notes

- Fagnano (1718–1723); Euler (1761); Gauss (1917)

- Gauss (1917) p. 199 used the symbols sl and cl for the lemniscate sine and cosine, respectively, and this notation is most common today: see e.g. Cox (1984) p. 316, Eymard & Lafon (2004) p. 204, and Lemmermeyer (2000) p. 240. Ayoub (1984) uses sinlem and coslem. Whittaker & Watson (1920) use the symbols sin lemn and cos lemn. Some sources use the generic letters s and c. Prasolov & Solovyev (1997) use the letter φ for the lemniscate sine and φ′ for its derivative.

- The circle is the unit-diameter circle centered at with polar equation the degree-2 clover under the definition from Cox & Shurman (2005). This is not the unit-radius circle centered at the origin. Notice that the lemniscate is the degree-4 clover.

- The fundamental periods and are "minimal" in the sense that they have the smallest absolute value of all periods whose real part is non-negative.

- Robinson (2019a) starts from this definition and thence derives other properties of the lemniscate functions.

- This map was the first ever picture of a Schwarz–Christoffel mapping, in Schwarz (1869) p. 113.

- Euler (1761); Siegel (1969). Prasolov & Solovyev (1997) use the polar-coordinate representation of the Lemniscate to derive differential arc length, but the result is the same.

- Reinhardt & Walker (2010a) §22.18.E6

- Siegel (1969); Schappacher (1997)

- Such numbers are OEIS sequence A003401.

- Abel (1827–1828); Rosen (1981); Prasolov & Solovyev (1997)

- Euler (1786); Sridharan (2004); Levien (2008)

- 2ϖi is also a period.

- Schappacher (1997). OEIS sequence A062539 lists the lemniscate constant's decimal digits.

- Levin (2006)

- Todd (1975)

- Cox (1984)

- Dark areas represent zeros, and bright areas represent poles. As the argument of changes from (excluding ) to , the colors go through cyan, blue , magneta, red , orange, yellow , green, and back to cyan .

- Combining the first and fourth identity gives . This identity is (incorrectly) given in Eymard & Lafon (2004) p. 226, without the minus sign at the front of the right-hand side.

- The even Gaussian integers are the residue class of 0, modulo 1 + i, the black squares on a checkerboard.

- Prasolov & Solovyev (1997); Robinson (2019a)

- Cox (2012)

- Reinhardt & Walker (2010a) §22.12.6, §22.12.12

- Analogously,

- Eymard & Lafon (2004) p. 227.

- Bottazzini & Gray (2013) p. 58

- Gauss, C. F. (1866). Werke (Band III) (in Latin and German). Herausgegeben der Königlichen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen. p. 405; there's an error on the page: the coefficient of should be , not .

- The function satisfies the differential equation (see Gauss (1866), p. 408). The function satisfies the differential equation

- If , then the coefficients are given by the recurrence with where are the Hurwitz numbers defined in Lemniscate elliptic functions § Hurwitz numbers.

- Zhuravskiy, A. M. (1941). Spravochnik po ellipticheskim funktsiyam (in Russian). Izd. Akad. Nauk. U.S.S.R.

- Lindqvist & Peetre (2001) generalizes the first of these forms.

- Ayoub (1984); Prasolov & Solovyev (1997)

- Euler (1761) §44 p. 79, §47 pp. 80–81

- Euler (1761) §46 p. 80

- In fact, .

- Cox & Hyde (2014)

- Gómez-Molleda & Lario (2019)

- The fourth root with the least positive principal argument is chosen.

- The restriction to positive and odd can be dropped in .

- Cox (2013) p. 142, Example 7.29(c)

- Rosen (1981)

- "A104203". The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences.

- Lomont, J.S.; Brillhart, John (2001). Elliptic Polynomials. CRC Press. pp. 12, 44. ISBN 1-58488-210-7.

- "A193543 - Oeis".

- Lomont, J.S.; Brillhart, John (2001). Elliptic Polynomials. CRC Press. ISBN 1-58488-210-7. p. 79, eq. 5.36

- Lomont, J.S.; Brillhart, John (2001). Elliptic Polynomials. CRC Press. ISBN 1-58488-210-7. p. 79, eq. 5. 36 and p. 78, eq. 5.33

- Robinson (2019a)

- is the Weierstrass elliptic function with periods and .

- Eymard & Lafon (2004) p. 234

- Armitage, J. V.; Eberlein, W. F. (2006). Elliptic Functions. Cambridge University Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-521-78563-1.

- The identity can be found in Greenhill (1892) p. 33.

- "A289695 - Oeis".

- Wall, H. S. (1948). Analytic Theory of Continued Fractions. Chelsea Publishing Company. pp. 374–375.

- Reinhardt & Walker (2010a) §22.20(ii)

- Carlson (2010) §19.8

- Dieckmann, Andreas. "Collection of Infinite Products and Series".

- Reinhardt & Walker (2010a) §22.12.12; Vigren & Dieckmann (2020) p. 7

- In general, and are not equivalent, but the resulting infinite sum is the same.

- Reinhardt & Walker (2010a) §22.11

- Reinhardt & Walker (2010a) §22.2.E7

- Berndt (1994) p. 247, 248, 253

- Reinhardt & Walker (2010a) §22.11.E1

- http://oeis.org/A175576

- Berndt, Bruce C. (1989). Ramanujan's Notebooks Part II. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4612-4530-8. p. 96

- Levin (2006) p. 515

- Levin (2006); Robinson (2019b)

- Cox (2012) p. 508, 509

- Arakawa, Tsuneo; Ibukiyama, Tomoyoshi; Kaneko, Masanobu (2014). Bernoulli Numbers and Zeta Functions. Springer. ISBN 978-4-431-54918-5. p. 203—206

- Equivalently, where and is the Jacobi epsilon function with modulus .

- The Bernoulli numbers can be determined by an analogous recurrence: where and .

- Katz, Nicholas M. (1975). "The congruences of Clausen — von Staudt and Kummer for Bernoulli-Hurwitz numbers". Mathematische Annalen. 216 (1): 1–4. See eq. (9)

- Hurwitz, Adolf (1963). Mathematische Werke: Band II (in German). Springer Basel AG. p. 370

- Arakawa et al. (2014) define by the expansion of

- Peirce (1879). Guyou (1887) and Adams (1925) introduced transverse and oblique aspects of the same projection, respectively. Also see Lee (1976). These authors write their projection formulas in terms of Jacobi elliptic functions, with a square lattice.

- Adams (1925)

- Adams (1925); Lee (1976).

- Rančić, Purser & Mesinger (1996); McGregor (2005).

External links

- Parker, Matt (2021). "What is the area of a Squircle?". Stand-up Maths. YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-19.

References

- Abel, Niels Henrik (1827–1828) "Recherches sur les fonctions elliptiques" [Research on elliptic functions] (in French). Crelle's Journal.

Part 1. 1827. 2 (2): 101–181. doi:10.1515/crll.1827.2.101.

Part 2. 1828. 3 (3): 160–190. doi:10.1515/crll.1828.3.160. - Adams, Oscar Sherman (1925). Elliptic functions applied to conformal world maps (PDF). US Government Printing Office.

- Ayoub, Raymond (1984). "The Lemniscate and Fagnano's Contributions to Elliptic Integrals". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 29 (2): 131–149. doi:10.1007/BF00348244.

- Berndt, Bruce C. (1994). Ramanujan's Notebooks Part IV (First ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-1-4612-6932-8.

- Bottazzini, Umberto; Gray, Jeremy (2013). Hidden Harmony – Geometric Fantasies: The Rise of Complex Function Theory. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-5725-1.

- Carlson, Billie C. (2010). "19. Elliptic Integrals". In Olver, Frank; et al. (eds.). NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions. Cambridge.

- Cox, David Archibald (January 1984). "The Arithmetic-Geometric Mean of Gauss". L'Enseignement Mathématique. 30 (2): 275–330.

- Cox, David Archibald; Shurman, Jerry (2005). "Geometry and number theory on clovers" (PDF). The American Mathematical Monthly. 112 (8): 682–704. doi:10.1080/00029890.2005.11920241.

- Cox, David Archibald (2012). "The Lemniscate". Galois Theory. Wiley. pp. 463–514. doi:10.1002/9781118218457.ch15.

- Cox, David Archibald (2013). Primes of the Form x2 + ny2 (Second ed.). Wiley.

- Cox, David Archibald; Hyde, Trevor (2014). "The Galois theory of the lemniscate" (PDF). Journal of Number Theory. 135: 43–59. arXiv:1208.2653. doi:10.1016/j.jnt.2013.08.006.

- Enneper, Alfred (1890) [1st ed. 1876]. "Note III: Historische Notizen über geometrische Anwendungen elliptischer Integrale." [Historical notes on geometric applications of elliptic integrals]. Elliptische Functionen, Theorie und Geschichte (in German). Nebert. pp. 524–547.

- Euler, Leonhard (1761). "Observationes de comparatione arcuum curvarum irrectificibilium" [Observations on the comparison of arcs of irrectifiable curves]. Novi Commentarii Academiae Scientiarum Imperialis Petropolitanae (in Latin). 6: 58–84. E252. (Figures)

- Euler, Leonhard (1786). "De miris proprietatibus curvae elasticae sub aequatione contentae" [On the amazing properties of elastic curves contained in equation ]. Acta Academiae Scientiarum Imperialis Petropolitanae (in Latin). 1782 (2): 34–61. E 605.

- Eymard, Pierre; Lafon, Jean-Pierre (2004). The Number Pi. Translated by Wilson, Stephen. American Mathematical Society. ISBN 0-8218-3246-8.

- Fagnano, Giulio Carlo (1718–1723) "Metodo per misurare la lemniscata" [Method for measuring the lemniscate]. Giornale de' letterati d'Italia (in Italian).

"Schediasma primo" [Part 1]. 1718. 29: 258–269.

"Giunte al primo schediasma" [Addendum to part 1]. 1723. 34: 197–207.

"Schediasma secondo" [Part 2]. 1718. 30: 87–111.

Reprinted as Fagnano (1850). "32–34. Metodo per misurare la lemniscata". Opere Matematiche, vol. 2. Allerighi e Segati. pp. 293–313. (Figures) - Gauss, Carl Friedrich (1917). Werke (Band X, Abteilung I) (in Latin and German). Herausgegeben der Königlichen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen.

- Gómez-Molleda, M. A.; Lario, Joan-C. (2019). "Ruler and Compass Constructions of the Equilateral Triangle and Pentagon in the Lemniscate Curve". The Mathematical Intelligencer. 41 (4): 17–21. doi:10.1007/s00283-019-09892-w.

- Greenhill, Alfred George (1892). The Applications of Elliptic Functions. MacMillan.

- Guyou, Émile (1887). "Nouveau système de projection de la sphère: Généralisation de la projection de Mercator" [New system of projection of the sphere]. Annales Hydrographiques. Série 2 (in French). 9: 16–35.

- Houzel, Christian (1978). "Fonctions elliptiques et intégrales abéliennes" [Elliptic functions and Abelian integrals]. In Dieudonné, Jean (ed.). Abrégé d'histoire des mathématiques, 1700–1900. II (in French). Hermann. pp. 1–113.

- Hyde, Trevor (2014). "A Wallis product on clovers" (PDF). The American Mathematical Monthly. 121 (3): 237–243. doi:10.4169/amer.math.monthly.121.03.237.

- Kubota, Tomio (1964). "Some arithmetical applications of an elliptic function". Crelle's Journal. 214/215: 141–145. doi:10.1515/crll.1964.214-215.141.

- Langer, Joel C.; Singer, David A. (2010). "Reflections on the Lemniscate of Bernoulli: The Forty-Eight Faces of a Mathematical Gem" (PDF). Milan Journal of Mathematics. 78 (2): 643–682. doi:10.1007/s00032-010-0124-5.

- Langer, Joel C.; Singer, David A. (2011). "The lemniscatic chessboard". Forum Geometricorum. 11: 183–199.

- Lawden, Derek Frank (1989). Elliptic Functions and Applications. Applied Mathematical Sciences. Vol. 80. Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-3980-0.

- Lee, Laurence Patrick (1976). Conformal Projections Based on Elliptic Functions. Cartographica Monograph. Vol. 16. University of Toronto Press.

- Lemmermeyer, Franz (2000). Reciprocity Laws: From Euler to Eisenstein. Springer. ISBN 3-540-66957-4.

- Levien, Raph (2008). The elastica: a mathematical history (PDF) (Technical report). University of California at Berkeley. UCB/EECS-2008-103.

- Levin, Aaron (2006). "A Geometric Interpretation of an Infinite Product for the Lemniscate Constant". The American Mathematical Monthly. 113 (6): 510–520. doi:10.2307/27641976.

- Lindqvist, Peter; Peetre, Jaak (2001). "Two Remarkable Identities, Called Twos, for Inverses to Some Abelian Integrals" (PDF). The American Mathematical Monthly. 108 (5): 403–410. doi:10.1080/00029890.2001.11919766.

- Markushevich, Aleksei Ivanovich (1966). The Remarkable Sine Functions. Elsevier.

- Markushevich, Aleksei Ivanovich (1992). Introduction to the Classical Theory of Abelian Functions. Translations of Mathematical Monographs. Vol. 96. American Mathematical Society. doi:10.1090/mmono/096.

- McGregor, John L. (2005). C-CAM: Geometric Aspects and Dynamical Formulation (Technical report). CSIRO Atmospheric Research. 70.

- McKean, Henry; Moll, Victor (1999). Elliptic Curves: Function Theory, Geometry, Arithmetic. Cambridge. ISBN 9780521582285.

- Milne-Thomson, Louis Melville (1964). "16. Jacobian Elliptic Functions and Theta Functions". In Abramowitz, Milton; Stegun, Irene Ann (eds.). Handbook of Mathematical Functions. National Bureau of Standards. pp. 567–585.

- Neuman, Edward (2007). "On Gauss lemniscate functions and lemniscatic mean" (PDF). Mathematica Pannonica. 18 (1): 77–94.

- Nishimura, Ryo (2015). "New properties of the lemniscate function and its transformation". Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications. 427 (1): 460–468. doi:10.1016/j.jmaa.2015.02.066.

- Ogawa, Takuma (2005). "Similarities between the trigonometric function and the lemniscate function from arithmetic view point". Tsukuba Journal of Mathematics. 29 (1).

- Peirce, Charles Sanders (1879). "A Quincuncial Projection of the Sphere". American Journal of Mathematics. 2 (4): 394–397. doi:10.2307/2369491.

- Popescu-Pampu, Patrick (2016). What is the Genus?. Lecture Notes in Mathematics. Vol. 2162. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-42312-8.

- Prasolov, Viktor; Solovyev, Yuri (1997). "4. Abel's Theorem on Division of Lemniscate". Elliptic functions and elliptic integrals. Translations of Mathematical Monographs. Vol. 170. American Mathematical Society. doi:10.1090/mmono/170.

- Rančić, Miodrag; Purser, R. James; Mesinger, Fedor (1996). "A global shallow-water model using an expanded spherical cube: Gnomonic versus conformal coordinates". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 122 (532): 959–982. doi:10.1002/qj.49712253209.

- Reinhardt, William P.; Walker, Peter L. (2010a). "22. Jacobian Elliptic Functions". In Olver, Frank; et al. (eds.). NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions. Cambridge.

- Reinhardt, William P.; Walker, Peter L. (2010b). "23. Weierstrass Elliptic and Modular Functions". In Olver, Frank; et al. (eds.). NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions. Cambridge.

- Robinson, Paul L. (2019a). "The Lemniscatic Functions". arXiv:1902.08614.

- Robinson, Paul L. (2019b). "The Elliptic Functions in a First-Order System". arXiv:1903.07147.

- Rosen, Michael (1981). "Abel's Theorem on the Lemniscate". The American Mathematical Monthly. 88 (6): 387–395. doi:10.2307/2321821.

- Roy, Ranjan (2017). Elliptic and Modular Functions from Gauss to Dedekind to Hecke. Cambridge University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-107-15938-9.

- Schappacher, Norbert (1997). "Some milestones of lemniscatomy" (PDF). In Sertöz, S. (ed.). Algebraic Geometry (Proceedings of Bilkent Summer School, August 7–19, 1995, Ankara, Turkey). Marcel Dekker. pp. 257–290.

- Schneider, Theodor (1937). "Arithmetische Untersuchungen elliptischer Integrale" [Arithmetic investigations of elliptic integrals]. Mathematische Annalen (in German). 113 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1007/BF01571618.

- Schwarz, Hermann Amandus (1869). "Ueber einige Abbildungsaufgaben" [About some mapping problems]. Crelle's Journal (in German). 70: 105–120. doi:10.1515/crll.1869.70.105.

- Siegel, Carl Ludwig (1969). "1. Elliptic Functions". Topics in Complex Function Theory, Vol. I. Wiley-Interscience. pp. 1–89. ISBN 0-471-60844-0.

- Snape, Jamie (2004). "Bernoulli's Lemniscate". Applications of Elliptic Functions in Classical and Algebraic Geometry (Thesis). University of Durham. pp. 50–56.

- Southard, Thomas H. (1964). "18. Weierstrass Elliptic and Related Functions". In Abramowitz, Milton; Stegun, Irene Ann (eds.). Handbook of Mathematical Functions. National Bureau of Standards. pp. 627–683.

- Sridharan, Ramaiyengar (2004) "Physics to Mathematics: from Lintearia to Lemniscate". Resonance.

"Part I". 9 (4): 21–29. doi:10.1007/BF02834853.

"Part II: Gauss and Landen's Work". 9 (6): 11–20. doi:10.1007/BF02839214. - Todd, John (1975). "The lemniscate constants". Communications of the ACM. 18 (1): 14–19. doi:10.1145/360569.360580.

- Vigren, Erik; Dieckmann, Andreas (21 June 2020). "Simple Solutions of Lattice Sums for Electric Fields Due to Infinitely Many Parallel Line Charges". Symmetry. 12 (6): 1040. doi:10.3390/sym12061040.

- Whittaker, Edmund Taylor; Watson, George Neville (1920) [1st ed. 1902]. "22.8 The lemniscate functions". A Course of Modern Analysis (3rd ed.). Cambridge. pp. 524–528.