Kamerun

Kamerun was an African colony of the German Empire from 1884 to 1920 in the region of today's Republic of Cameroon. Kamerun also included northern parts of Gabon and the Congo with western parts of the Central African Republic, southwestern parts of Chad and far northeastern parts of Nigeria.

Kamerun | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1884–1920 | |||||||||||||||||||

Service flag of the Colonial Office

Coat of arms of the German Empire

| |||||||||||||||||||

Location of Kamerun: Green: Territory comprising German colony of Kamerun Dark grey: Other German territories Darkest grey: German Empire | |||||||||||||||||||

| Status | German colony | ||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Jaunde | ||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | German (official) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Colony | ||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||||||||||

• 1884 (first) | Gustav Nachtigal | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1914–1916 (last) | Karl Ebermaier | ||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||

• Established | 17 August 1884 | ||||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1920 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1910 | 495,000 km2 (191,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1912 | 790,000 km2 (310,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||

• 1910 | 2.600.000 | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1912 | 4.645.000 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | German gold mark | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Cameroun and Nigeria | ||||||||||||||||||

History

Years preceding colonization (1868–1883)

The first German trading post in the Duala area [1] on the Kamerun River delta[2] was established in 1868 by the Hamburg trading company C. Woermann. The firm's primary agent in Gabon, Johannes Thormählen, expanded activities to the Kamerun River delta. In 1874, together with the Woermann agent in Liberia, Wilhelm Jantzen, the two merchants founded their own company, Jantzen & Thormählen ther

Initial colonization (1884–1889/90)

The official beginning of the German "Protectorate of Cameroon" was on 17 August 1884.[3] Gustav Nachtigal had arrived in Duala in July and negotiated a treaty with a number of rulers local to the region around Duala, at that time the center of Germany's trading operations. From there, he would go on to other parts of Cameroon, securing further treaties with a number of tribes of the regions around the rivers, where trade was already well established. This would establish a trend of using treaties as one method of expanding German control.[4]

As mentioned above, one of the primary motivations for the colony was German corporations seeking to expand their economic interests in Cameroon. Bismarck, being aware of this fact and concerned about the substantial costs of a directly administered colony, opted to instead grant the companies already involved in Cameroon a "Chartered" status.[5] As such, initial government fell to large German trading companies and concession companies who had already established themselves in the colony.[5]

Eventually, however, it was revealed that the companies were not performing their administrative duties very well. A variety of factors contributed to their failure, but foremost among them were ongoing conflicts with local traders as the traders began to move further inland. This got bad enough that it necessitated the German government stepping in and officially taking over.[6]

Expansionary era of colonization (1890–1906)

From thereon out the administration of the colonies would be at the hands of the German administrators. Regardless, the focus of the colony remained the same: to support the plantation industry and the trade of the German companies. As such, this time saw major expansion in the agricultural industry, and efforts were taken to expand further into the landlocked areas of Cameroon to better trade opportunities and German access to the African interior.[6]

The most notable of the German governors, and the man who would come to define the German legacy in Cameroon, would be Jesko Von Puttkammer, who governed from 1895–1906 (and for a few shorter times before).[7] It was Puttkammer who began the German behaviors that lend them a reputation of brutality and harshness as colonizers. During his time, he oversaw a number of military campaigns against local peoples like the Bali, forcing those who rebuffed German attempts at a "treaty" that supposedly justified German expansion.[8] Oftentimes, he would not act directly against these people, instead relying on empowering other rival local powers and establishing them as "protected by Germany" and arming them.[7] These groups would then use their newfound power and armaments to conquer dissenting peoples, without the Germans themselves actually ever getting involved.

When the Germans did become involved, however, it was brutal, often going out of their way to punish those who surrendered to them if their leader still refused, and taking a tithe of people from conquered peoples as essentially slaves, though they did not call them such.[8]

This leads into the second prominent feature of Puttkamer's governorship, his expansion and support for the plantations. This became a problem, as the plantations had more fields than they did workers, so there was a labor shortage. To address this, Puttkamer instituted the "man tithes" mentioned above, in addition to just taking people whenever they conquered new territories or had to put down a rebellion.[7] These people would then be made to do harsh forced labor, with extremely high rates of death.[7] Extreme forms of discipline were practiced too, including the cutting of hands, genitals, gouging of eyes and decapitations. Severed limbs were often collected and shown to local authorities as proof of death.[8]

These practices, which continued even after Puttkammer retired from his position, would define the German colonial legacy.[9]

Final years (1907–1916)

After Puttkamer left his position, aggressive expansion was less common (though more territory would be added via diplomatic means), and the colony began to focus more on development.[5] With subsidies from the imperial treasury, the colony built two rail lines from the port city of Duala to bring agricultural products to market. The Northern line extended 160-kilometre (99 mi) to the Manenguba mountains, and the 300-kilometre (190 mi) mainline went to Makak on the river Nyong.[10] An extensive postal and telegraph system and a river navigation network with government ships connected the coast to the interior.

The Cameroon protectorate was enlarged with New Cameroon (German: Neukamerun) in 1911 as part of the settlement of the Agadir Crisis, resolved by the Treaty of Fez.[11]

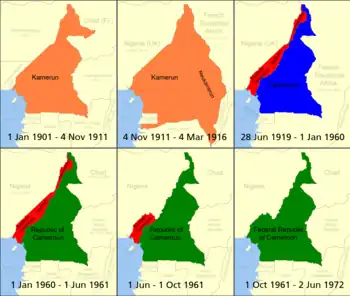

Loss of Cameroon as a colony

At the outbreak of World War I, French, Belgian and British troops invaded the German colony in 1914 and fully occupied it during the Kamerun campaign.[12] Following Germany's defeat, the Treaty of Versailles divided the territory into two League of Nations mandates (Class B) under the administration of the United Kingdom and France.[12] French Cameroon and part of British Cameroon reunified in 1961 to form present-day Cameroon.

Notably, this did not end German involvement in Cameroon, as many former German plantation owners bought their plantations back in the 1920s and 30s.[9] It would take until World War II before Germany was "fully out" of Cameroon.

Gallery

German surveyor in Kamerun, 1884

German surveyor in Kamerun, 1884 Policemen at Duala on the Kaiser's birthday, 1901

Policemen at Duala on the Kaiser's birthday, 1901 Bananas being loaded for export to Germany, 1912

Bananas being loaded for export to Germany, 1912

Governors

Planned symbols for Kamerun

In 1914 a series of drafts were made for proposed Coat of Arms and Flags for the German Colonies. However, World War I broke out before the designs were finished and implemented and the symbols were never actually used.

Proposed flag

Proposed flag Proposed coat of arms

Proposed coat of arms

See also

- Elo Sambo

- German East Africa

- German South West Africa

- German West African Company

- History of Cameroon

- Index: German colonisation in Africa

- Iwindo

- Kamerun campaign

- New Cameroon

- Ossidinge

- Togoland

Footnotes

- present-day Douala

- now the Wouri River delta

- Diduk, Susan (1993). "European Alcohol, History, and the State in Cameroon". African Studies Review. 36 (1): 1–42. doi:10.2307/525506. ISSN 0002-0206. JSTOR 525506. S2CID 144978622.

- Schaper, Ulrike (2016-09-02). "David Meetom: Interpreting, Power and the Risks of Intermediation in the Initial Phase of German Colonial Rule in Cameroon". The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 44 (5): 752–776. doi:10.1080/03086534.2016.1229259. ISSN 0308-6534. S2CID 152280180.

- Ardener, Edwin (1962). "The Political History of Cameroon". The World Today. 18 (8): 341–350. ISSN 0043-9134. JSTOR 40393427.

- Linden, Mieke van der (2016). Chapter 7: German Cameroon. Brill Nijhoff. ISBN 978-90-04-32119-9.

- Anthony, Ndi (2014). Southern West Cameroon Revisited Volume Two: North-South West Nexus 1858–1972. Langaa RPCIG. ISBN 978-9956-791-32-3.

- Terretta, Meredith (2013). Nation of Outlaws, State of Violence: Nationalism, Grassfields Tradition, and State Building in Cameroon. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-4472-6.

- Njung, George (2019). "The British Cameroons mandate regime: The roots of the twenty-first-century political crisis in Cameroon." The American Historical Review 124, no. 5 (2019): 1715–1722". The American Historical Review. 124 – via Oxford Academic.

- This line was later extended to the current Cameroon capital of Yaoundé.

- Dibie, Robert A. (2017). Business and Government Relations in Africa. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-79266-0.

- Elango, Lovett (1985). "The Anglo-French "Condominium" in Cameroon, 1914–1916: The Myth and the Reality". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 18 (4): 657–673. doi:10.2307/218801. ISSN 0361-7882. JSTOR 218801.

External links

- Cana, Frank Richardson (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). pp. 110–113.

- Banknotes of German Cameroon