John V of Parthenay

Jean V de Parthenay-L'Archevêque, or Larchevêque, Sieur de Soubise, born posthumously in 1512 and died at Parc Soubise in Mouchamps in Vendée, on 1 September 1566, was a Protestant French nobleman, last lord of Mouchamps, from a younger branch of the Parthenay-l'Archevêque family. His mother is the humanist Michelle de Saubonne; his daughter and heiress Catherine de Parthenay, the last of the name, married René II de Rohan for a second time in 1575.

Jean V de Parthenay-L'Archevêque | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1512 |

| Died | 1 September 1566 (age 53 or 54) |

| Occupation(s) | Military leader, diplomat |

| Children | Catherine of Parthenay |

| Parents |

|

Fighter and ambassador of Henry II during the last wars of Italy, he was in the service of the king, whom he accompanied since childhood. Officially converted to Calvinism in 1562, after the massacre of Wassy, he became during the first war of religion one of the most ardent supporters of Condé and the Huguenots. His deeds and gestures are known through the memoirs of his life[1] as recorded by the mathematician François Viète, his lawyer and secretary between 1564 and 1566. They were published in 1879 by Jules Bonnot and extensively commented on and popularized by Frédéric Ritter and Benjamin Fillon.

A close friend of King Henry II, then of the regent Catherine de Medici, Soubise was accused of having ordered the death of the duke of Guise. His government of the city of Lyons (1563) nevertheless spared Catholics the cruelties of the Baron des Adrets; and, until his death in 1566, his efforts helped keep the peace between the warring factions. For a time, he even hoped to convert the queen-mother to the doctrine of the Calvinists. According to the 16th century historian Jacques-Auguste de Thou,“Jean de Parthenay combined an august birth with great moderation and uncommon skill."[2]

A young gentleman

Jean V de Parthenay is the only son of Jean IV, lord of the Soubise park located in Mouchamps in Vendée, lord of Pauldon, of Vendrennes, of the Goyau fief and of Mouchamps. His mother is Michelle du Fresne called de Saubonne, the femina cordatissima of Guillaume Budé.[3] She is also known to be Bernard Palissy's first protector.[4] When her father died, her mother is a lady-in-waiting to Renée de France.[5] It is a scholar, who introduced Clément Marot to the court. Jean V de Parthenay served as a child of honor to Henry II, who was seven years younger than him. He himself was carefully educated in the knowledge of the humanities, and was then regarded as one of the most cultured young people of his time.

In 1527, on the occasion of a famous trial, the humanist Guillaume Budé noted his fervor and his knowledge of good letters and revealed this young page. His name is the origin of the expression causa soubisana.[6]

I was involved in the illustrious trial of Jean, called the Achevêque, a young boy who, at court and among very high personages, stood out for his fervor and his knowledge of good letters. He is endowed, moreover, with all the other privileged ornaments of the nobility, which have been brought to him both by nature and by the education of his mother, a lady of great wisdom formerly known by her name among the people of the court.

In 1528, his mother, two of his sisters and himself went to Italy, to Ferrara, Renée of France having married Hercule II d'Este; Clément Marot joined them there shortly after.[7] Jean de Parthenay learned there to love Italy,[8] where he later returned during many trips.

In 1536, his mother was expelled from Ferrara along with all the French from the court of Hercules II. This return is sung by Clément Marot:[9]

Come sweet weather, retire, wind,

Do not annoy Madame de Soubise: Enough she has annoying sadness

To abandon her lady and her mistress.

Jean V de Parthenay Sieur de Soubise then took up the profession of arms. A favorite of the Duke of Orléans, the Dauphin and his brother, he was from then on in all of Henry II's wars.[10] Appointed ordinary gentleman of the king's chamber, then governor and bailiff of Chartres in 1539,[11] he was a prisoner for a year in Lille, in Flanders. Captured, he did not want to be named and made himself known to his jailers under the impromptu assumed name of Ambleville.[12] His memoirs state that having forgotten the name given to his enemies, he took more than two hours to find it. The rest of his captivity is softened by the attention paid to him by the wife and daughter of his keeper.[13] On his return, he took sides against the Guises and attached himself to the Châtillon family, with whom he was like a fourth brother.[14]

In 1549, the death of his mother followed by five days that of his sister Anne de Parthenay, married to the Sieur du Pons.[15]

Military career and Italian wars

In September 1552, Jean de Parthenay was sent to Nancy by Henri II to sound out the Count of Vaudémont.[16] The latter, betting on the respect of the neutrality of Lorraine by the Emperor Charles V, declines the offer of the King of France. From October 1552 to the first days of January 1553, Jean de Parthenay participated in the siege of Metz.[17]

On 4 January 1553, Jean de Parthenay receives the order of King Henry II to go to meet the Duke of Parma and take him to Fontainebleau. On 9 May, back in Paris, he married Antoinette Bouchard, daughter of François II, Baron d'Aubeterre, and Isabelle de Saint-Seine, his first wife.[9] Antoinette d'Aubeterre was then a companion to Queen Catherine de Medici; born in 1532, she is twenty years younger than her husband but from their marriage, it is she who takes charge of the management of the Soubise park, calling for example Bernard Palissy and Philibert Hamelin, whom she protects, to settle some differences between Soubise and his vassals.[18][19]

Barely married, Jean de Parthenay receives the order to go to Picardy to fight for Thérouanne and Hesdin. This time, the king's armies suffered a terrible defeat. They are commissioned by Antoine de Bourbon, whose wife Jeanne d'Albret awaits the future Henri IV; she remains at the scene of the fight with her husband. Antoine de Bourbon saves Hesdin from the hands of the Imperials but loses Thérouanne between May and June. A few months later, Charles V took over and razed the two strongholds.[20] That year his wife gave birth to a son. The newborn, their only male child, lived only five weeks. With this infant the younger branch of the Parthenay-L'Archevêque died out.

Around the month of July 1552, Henry II discovers the rapprochement between the Duke of Parma, Ottavio Farnese and the King of Spain Philip II. The king, his advisers and Cardinal Carafa decide to act. The Guises had Jean de Parthenay sent on a mission to Parma to get him away. He must propose to the Duke an alliance with the King of France and ask him for the hand of his son Oratio to unite him with Diane d'Angoulême. It is also endowed with letters from Henry II to give to the Duke of Ferrara in order to rally him and ask him to join the Pope in combating Spanish intrigues.[21]

Jean de Parthenay was appointed lieutenant general there for His Majesty, then resided in Siena; of 25 November 1554. On 25 February, he remained in Parma, at the rate of 500 pounds per month and helped to keep the duke in a benevolent neutrality with regard to the French (but Farnese ended up getting closer to Philip II two years later); at the same time, Jean de Parthenay attends, without being able to help him, for lack of troops, at the capitulation of Montluc, in Siena on 17 April.[22][23]

On 22 March 1554, his wife, Antoinette d'Aubeterre gives birth to Catherine, future woman of letters and action, writer, mathematician and protector of science. Through her, Jean V de Parthenay is one of the ancestors of the house of Rohan. The following year, Jean de Parthenay went up to attack Denain and nearly lost his life during the assault he gave with Admiral de Coligny, because, wounded in the head and thrown to the ground, he lacked and find himself choked by his own helm. He nevertheless continued the assault bareheaded until the end of the fighting.[24]

In 1555, Jean de Parthenay commissioned surveying work from Bernard Palissy.[25]

After the bloody defeat of Saint-Quentin on 10 August 1557, and a few months later at the capture of Calais, on 3 January 1558. He became friends there with Marshal Strozzi,[26] himself an enemy of the Guise (the duke commanded their army). The memoirs of his life restore their dialogue:

"Are we not very miserable," Strozzi asks him, "to hazard ourselves every day and take so much trouble to enlarge and bring the honor of our labor to those who would like to have us ruined and who will one day be the cause of the ruin of France? » “ It is true, replies Soubise, but since our honor, our duty and the service of our king commands us to do so, we have to do it ”

In August 1558 the king granted John V of Parthenay a gratuity of 6,900 pounds as a reward for the wars in Italy and "others". But, by the boldness of his words and the foresight of his military views during councils of war, Jean de Parthenay made himself an enemy of Marshal de Tavannes.[26]

From Amboise to Wassy, the shift

The Renaudie affair

Since 1557 and the Protestant celebrations of Pré-aux-Clercs in Paris (from 13 to 19 May 1558) attended by Antoine de Navarre and his brother the Prince of Condé, many gentlemen drew closer to the Reformed faith.[27] This is the case with the Parthenays; and Jean de Parthenay feels carried towards the new religion. Antoinette d'Aubeterre, his wife preaches on his land. But for his part, he hesitated to profess it publicly, still waiting some time to make his conversion known.[26]

When King Henry II died the following year, his son François II succeeded him. He was only fifteen years old, and does not reign for two years. A friend of Jean de Parthenay, Jean du Barry lord of La Renaudie, then imagined removing the queen-mother and the young king to remove them from the influence of the Guise.[28]

La Renaudie takes the lead in the conspiracy[29] which originated in December 1559, in Geneva, shortly after the execution of Anne du Bourg. Its goal is to impose around the young king a council of regency, where the princes of blood, particularly Condé, must hold the first place. Antoine de Bourbon is opposed to it as well as Calvin; it does not seem that the latter nor Théodore de Bèze were really informed of the real aims of the conspirators.[30] La Renaudie was personally angry with François and Charles de Guise who had his brother-in-law arrested and executed. He gave himself as accomplices a few friends, Raunay, Baron Charles de Castelnau, François d'Aubeterre (Jean de Parthenay's own brother-in-law),[31] Edme de Ferrière-Maligny (brother of Jean II de Ferrières), Captain Mazères, but also the father of Agrippa d'Aubigne. If the Guises resist, the conspirators promise to massacre them. La Renaudie, who linked up with Soubise at the siege of Metz, confided to him his intention of seizing the king from the month of September 1559, at a time when the conspiracy was far from having taken shape.[32]

A first assembly of conspirators was held in Nantes in February 1560, and their troops, nearly 500 men, split up with the intention of moving towards Blois, Tours and Orléans. The operation was scheduled for 10 March 1560;[33] it was in fact postponed to 17 March. However, from 12 February, the Guises, warned by the Parisian lawyer with whom La Renaudie is staying, were made aware of the plot. They decide to take refuge in Amboise. Condé d'Andelot, Coligny and Odet de Chatillon, taken into confidence by La Renaudie, then preferred to negotiate with the Guise an amnesty for Protestants with the exception of the conspirators.[34]

On 15 March, the duke of Nemours seizes the castle of Noizay, where some of the conspirators have gathered. Condemned for the crime of lèse-majesté, Castelnau, Mazères and Raunay died beheaded or hanged at the windows of the castle of Amboise.[35] For the next few days, La Renaudie was nowhere to be found. Jean de Parthenay, for his part, is retained by the service of the queen mother. He is interrogated by her, who tries to extract from him the name of the place where his friend is hiding.[36]

"When I know, I'd rather be dead than say it," he replies.

The Queen Mother assures him that he need fear nothing if La Renaudie has done nothing against the King. Jean de Parthenay replies:

"I know well that it will be found that he acted against the king, since he acted against those of Guise, because today in France it is a criminal lèse-majesté to have acted against them, of as indeed they are the ones who are kings."

According to his memoirs, "You can't get anything else out of his mouth."

The conspiracy ends in a massacre. Bertrand de Chandieu's troops moving on 17 March, towards Amboise are destroyed; La Renaudie is killed on 19 March.[37] His body is cut into five pieces and exposed at the gates of Amboise. One of his servants underwent several interrogations, without ever pronouncing the name of Jean de Parthenay.

Conversion

After the La Renaudie affair, Condé's situation at court became untenable. The prince is suspected of having participated in the conspiracy. But the Guises, weakened by the general discontent, cannot attempt anything against him without written proof of his guilt. During the summer of 1560, Condé took an active part in setting up a new conspiracy against the Guise. His undertakings having been discovered, he was arrested at Orléans on the personal order of the king. Illness and then death of the latter made him avoid execution, set him free and took power away from the Lorraine princes.

Jean de Parthenay loves the court. François Viète shows in his biography that he also loves its pleasures.[38] On 7 December 1561, he was made a knight of the king's order at Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Queen Catherine de Medici wants to attach it to herself, as she wants to attach to herself everything that can counterbalance the power of the Guises. The new king, Charles IX, was ten years old when he came to the throne. On 17 January 1562, the Edict of Saint-Germain or Edict of January gave many assurances to Protestants but the Parliament of Paris, very Catholic, refused to register this royal act of tolerance.

Shortly after, Jean de Parthenay announced "loyally" to Catherine de Medici his intention to abandon the mass.[39] She tries to stop him and promises him the greatest charges in the kingdom. She offers him tutoring from young King Charles. Finally, she asks him to only say “le presche” on her lands at night. He promises him to tell it two or three times to his peasants and his vassals, but protests that he will not force them if they refuse to do so.[40] Finally, he retired to Parc Soubise, not without protesting his friendship to the queen and his regret at not having “two souls” to use one to serve her.

The queen, anxious to retain support, sent him the order of Saint-Michel, as if to invite him to return.[28]

The Massacre of Wassy

On 1 March 1562, the Duke François de Guise passing through Wassy in Champagne, sends his armed men to interrupt a Protestant ceremony; 500 Huguenots are forced out of their place of worship hastily. Men, women and children, they are treated as armed rebels, about fifty are killed, more than a hundred wounded.[41][42]

This massacre, which has nothing fortuitous, goes down in history as the massacre of Wassy and truly sets in motion half a century of religious wars.[43] It is soon followed by those of Cahors, Carcassonne, Tours, Auxerre, Avignon etc.[44] Jean de Parthenay learns of the event at Fontainebleau, where he has gone to thank the king for his previous kindness; he convinces him to join Condé 's party .

Jean de Parthenay, citing the sympathies the queen once declared for Calvin, made great efforts to win Catherine Medici over to the reform party.[45] He spent hours with her and with Chancellor de L'Hospital. The Guises, who want to get their hands on power, go to Fontainebleau. The queen trembles for the kingdom at their approach, but Jean de Parthenay cannot convince her to flee. She begs him to stay and then asks him not to take up arms. It is too late: Jean de Parthenay reveals to her that he will join forces with those of his friends, to deliver her and to deliver the king from the captivity to which the Lorraine party will reduce him.[46]

The protestant captain

Jean V de Parthenay-L'Archevêque became one of the best Protestant captains acting under the orders of Condé at the start of the Wars of Religion.[47]

Lyon headquarters

Having left Fontainebleau, Jean de Parthenay came to meet Admiral de Coligny and Condé in Meaux. Their army passed under the walls of Paris and took the road to Orleans. Condé, Coligny, d'Andelot, La Rochefoucauld and Soubise went to find the queen near Beaugency. Their conference produced no results.[48] Shortly after, Jean de Parthenay nearly died of fever. Barely recovered, he was sent to Lyon by Condé.

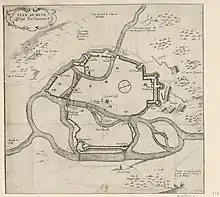

He left on horseback with forty gentlemen, including his chaplain, Claude Courtois, Sieur de Lessart.[49] He crosses the Vivarais, Burgundy, where the bailly of Autun follows him for three days with 120 men without daring to attack him. He took command of Lyon on the 15 or 19 July 1562, with the full powers of the Prince of Condé (letters dated 25 May) in order to counterbalance the abuses and cruelties of the Baron des Adrets. He joins forces for this with Charles Dupuy de Montbrun.[50][49]

Catherine de Medici wrote to him several times asking him to return the city. Jean V de Parthenay replied that “as long as he was governor of Lyon, he would keep it faithfully in the name of the king and queen."

He must then face the Catholic armies of the duke of Nemours. One of the most valiant leaders of the Protestant party on the eve of Saint Barthélemy, Jean V de Parthenay managed to hold the city until the pacification edict of 19 March 1563. This siege is illustrated two years later by the “speech that occurred in the city of Lion [Lyon] while Monsieur Soubise commanded there”, a pleading attributed to François Viète and published (for the first time in the 19th century ) by Hector de the Ferriere. Although suspected of sympathy with Soubise, the document reveals how Soubise manages to feed Lyon during his siege and in what resolution he finds himself facing the Duke of Nemours. It also gives to read that Jean de Parthenay maintains freedom of worship.[21][51]

During this siege, Jean de Parthenay organizes the supply of the city by the Dombes, which attracts him the unfailing hatred of the Duke of Montpensier.[52]

The Assassination of the Duke of Guise

On the eve of entering Orléans, Duke François de Guise was killed by Poltrot de Méré. When questioned, the latter denounced Théodore de Bèze, Admiral de Coligny and Jean de Parthenay. The admiral responds to these accusations but Jean de Parthenay, who is locked up in Lyon, cannot add his name to the protest of 12 March 1563, signed by Châtillon, La Rochefoucauld and De Bèze.[53]

The presumptions against Jean de Parthenay are as follows: Méré is related to La Renaudie; he is from the house of Aubeterre; he accomplished with Jean de Parthenay the journey from Orleans to Lyons; during the siege of Lyons he spoke of killing de Guise, and during a truce he boasted to the troops of the Duke of Nemours that he could put him down as easily as game.[54]

"He [Poltrot de Méré] saw a deer pass by and said to them: 'Do you want me to show you how I will do to M. de Guise?' and saying that shoots him with a harquebus by the head, and kills him, for he was just a harquebusier."

Moreover, during the siege, Jean de Parthenay sent Poltrot to Admiral de Coligny and their accusers saw in this evidence of a plot.[55]

Antoinette d'Aubeterre then hired, with the agreement of her husband, one of the most famous young Poitevin lawyers, the future master of requests of Henri III and Henri IV, the cryptographer and mathematician François Viète. Jean de Parthenay approves it on his return from Lyon, after having returned the keys of this city to the lord of Gordes. François Viète whose basic training is legal has already pleaded several victorious trials; he is not known as a Protestant and comes to settle in the Soubise park at the beginning of the year 1564 in order to consult the genealogical archives. Thanks to him, Jean de Parthenay manages to wash away any suspicion of complicity.

For his defense, his lawyer accompanies Jean de Parthenay to Lyon to look for traces of his actions while the documents are still in the hands of Marshal de Vieuville, Lord of Gordes. He then produced a memoir in which he simply gave to read the nobility of Jean de Parthenay's behavior the previous year, during his administration of the city of Lyon (admirable for his qualities in supplying according to Jacques Auguste de Thou).[49] Viète also maintains that his master remained faithful to the king when he commanded Lyon and specifies that Soubise did not submit to Nemours, contrary to the requests made to him by the queen, for fear that the latter (and King Charles IX) were the prisoners of the Guise.

Last fights

In order to write his memoirs, an account of his life and the genealogy of the Parthenays were commissioned from François Viète. The name of the Parthenays is therefore linked to the fate of the great mathematician. After Viète went with him to Lyon to illustrate his defense in 1564, the lawyer was assigned the role of tutor to Soubise's daughter, the already learned Catherine de Parthenay.[56] Later, by defending their friend Françoise de Rohan, in her trial against the Duke of Nemours, the founder of algebra widened this circle of protectors to the Rohans, who were more powerful and better able to propel him towards the court of King Charles IX from France .

Peace made, Jean de Parthenay acquitted returned to the good graces of the queen and tried again to bring her back to the cause of the Calvinists.[57] He pays court to her in Lyon, during her visit, and stays with her for a long time. He saw her again in Niort, during her trip to Bayonne, and accompanied her to La Rochelle.[58][59] He no longer benefited from the complicity of the Duchess of Montpensier, who died in 1561, but again encountered the jealousy of her husband, the Duke Louis III of Montpensier.[60] Returning home after his visit to La Rochelle, Parthenay declared to Antoinette d'Aubeterre that there was nothing more to hope for on that side. Catherine de Medici now refuses to admit before him her former sympathies for the reformed religion.[61]

In October 1565, he saw Catherine de Medici again in Meaux and in April 1566, one last time in Moulins where he was almost assassinated with all the Huguenot leaders present in this city.[62]

Returning from Moulins at the beginning of the summer of 1566, Jean de Parthenay fell seriously ill.[62] He refused to go to bed but spends most of his days in his room.

On 8 August 1566, Jean de Parthenay writes his will and declares that he wants to be buried according to the form and manner observed by the Reformed churches of the kingdom.[63]

Sunday, first September 1566, his wife, who watches over him, receives her last breath. A quarter of an hour before dying, he gives his blessing to his daughter. His last words are to place his soul in the hands of God.[64]

François Viète testifies that the day before again, he received a Calvinist Lorraine gentleman and talked to him all morning in the gardens of the Soubise park about things in the kingdom of which he remains aware more than anyone else.[65] The future founder of algebra declares that he never heard him speak so well as on the eve of his death.

Immediately, the Huguenot party expressed its sadness to his wife and daughter.[49] The Queen of Navarre, Jeanne d'Albret, their military leader, Admiral de Coligny, and their spiritual leader, Théodore de Bèze sent their condolences to them.[66]

Antoinette de Parthenay then died in 1580.

According to La Popelinière, Jean de Parthenay was "a gentleman of fine appearance, endowed with great estates and estates, liberal and honorable in all his actions, grave in speech and manners, affable and gracious nevertheless in conversation, disdainful of his domestic affairs as much as affectionate to the public and especially to the good of the kingdom, diligent and enemy of the birds”.[2] His biographer adds that he regularly went to bed at midnight to wake up at four o'clock in the morning and spend part of the night rushing his business .

It is believed that he died of jaundice, the same ailment from which his wife later suffered.

Jean de Parthenay

A chaotic fate

Raised by his mother in contact with the classical humanities, frequenting poets from an early age and nurtured by his sister Anne of Latin or Greek texts, Jean de Parthenay hardly seems predestined for the military career in which his life was subsequently worn out.[67] Child of honor of the Dauphin Henri II,[57] he seems destined for the pleasures of the court but his meeting with Calvin in Ferrara will decide otherwise. Because the animosity of the Lorraine party will pursue him from then on. By removing him from the king's favors, she condemns him to lead the hard life of the military.[68]

However, the party of Lorraine princes and, during the following century, some Catholic historians, Brantôme, Antoine Varillas, then Bossuet, the eagle of Meaux, hardly credit him with these good deeds. They also suspect him of having been involved in the conspiracy of La Renaudie, even of being one of the instigators of the assassination of Duke François de Guise.[69][70] Whatever efforts his secretary may have expended to exculpate him, Jean de Parthenay, Sieur de Soubise, still remains for them one of the culprits of these plots. Bossuet even saw an encouragement in the words that Jean de Parthenay launched to Poltrot du Méré, who had come to confess to him "that he had resolved in his mind to deliver France from so much misery, by killing the Duc de Guisse"; usual words with him, to which Jean de Parthenay would have replied:

“that he did his usual duty; [and for what he had proposed to her, that] God would know how to provide for it by other means."

He could not find peace and, although he harbors few illusions as to his chances of converting the Queen Mother to the "true religion", his repeated, incessant efforts for him cause the party of Lorraine to abandon their last forces fairly quickly.[71][14]

The judgement of posterity

Upon the death of Jean de Parthenay, his daughter and heiress Catherine became Dame de Soubise. She first marries Charles de Quellenec baron du Pont then in second marriage René II de Rohan to whom she brings the land of Soubise which then passes to their youngest son Benjamin de Rohan duke of Frontenay.[72] On his death in 1642, the seigneury of Soubise passed to his niece the Duchess of Rohan, who bequeathed it to her daughter Anne de Rohan-Chabot, wife of his cousin François de Rohan. The seigneury of Soubise was erected by letters patent (unregistered) of Louis XIV dated March 1667, in the Principality of Soubise in favor of François de Rohan (1630–1712).[73][74] The latter's grandson Charles de Rohan-Soubise, Marshal of France protected by the Marquise de Pompadour, left the memory of an incapable favourite, leaving his men to be massacred at the Battle of Rossbach in 1757. A song , "les reproaches de The Tulip to Madame de Pompadour” recounts this episode. Its lyrics have been attributed to Voltaire.

Brantôme and Bossuet were extremely severe against Jean de Parthenay. For one as for the other, he was the accomplice of the assassin of François de Guise.[75] Jean-Antoine Roucher[76] says of the first:

“Brantôme charged his memory. He positively accuses him of having incited Poltrot to the assassination of the Duc de Guise: but as Jean Le Laboureur has well remarked , Brantôme enveloped the Sieur de Soubise in the hatred he bore to the Lord of Aubeterre."

The second recognizes by himself:[77]

“[Queen Catherine de Medici] had continual talks with Soubise, a man of great quality, devoted to the Huguenot party and well instructed in the new doctrine. "

The memory of Jean de Parthenay, however, was never completely erased. Antoine Varillas read his memoirs and took it for granted that Catherine de Medici had some Protestant leanings, or at least that she was Catholic only out of politics. In the 18th century, Dreux du Radier remembers that Jean de Parthenay failed to convert Queen Catherine de Medici to Protestantism and Louis Moréri[78][79] mentions his figure in his large dictionary, and recognizes him as "a man of great merit and great service". In the 19th century, with the revival of Protestant studies, however, the figure of Jean de Parthenay regained prominence. Eugène and Émile Haag, Auguste-François Lièvre, Jules Bonnet, Hector de la Ferrière, Auguste Laugelbring to light all that is chivalrous in his attitude. Finally, the rediscovery of François Viète by Frédéric Ritter and Benjamin Fillon naturally leads many historians of science to focus on this minor nobility of Poitou, open to new ideas, keen on Greek, Latin and Hebrew, a small protective circle of an astonishing master of requests, who, starting from the bottom, was awakened to mathematics by a 12-year-old girl, served as secretary to her father, and was about to found the new algebra.[80] Protector of Palissy, father of a young scholar, it is also in this capacity that Jean de Parthenay also deserves to be known, as the first protector of a founding mathematician.[81]

Some dating issues

For some authors, who confuse him with his son-in-law, Jean Parthenay would have died during the Massacre of Saint Bartholomew. For others, he would have survived these massacres, and on 13 May 1573, his wife, Antoinette, taken prisoner under the city of Lyons, wrote to him to "rather let her perish than betray her cause".[82] These two versions are aberrant. Contradicted by the documents and the fact that Antoinette de Parthenay married Catherine at the end of her widowhood to Charles de Quellenec, Baron de Pont (1668) in order to assure her of support of which her father's death deprived her. The courage of Antoinette d'Aubeterre having manifested itself in 1563 and in a less romantic way.[83]

The error is due to Agrippa d'Aubigné, who in his history of the wars of religion confuses the son-in-law with his father-in-law. It is noted in its time by Pierre Bayle.[82] One of the best references on these questions is still the article published by Auguste Laugel in the Revue des deux Mondes in 1879.

See also

Notes and references

- François Viète, Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque (1879). Mémoires de la vie de Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque, sieur de Soubise [by F. Viète ... (in French). Oxford University.

- Lièvre, Auguste-François (1860). Histoire des protestants et des églises réformées du Poitou (in French). Grassart.

- François Viète, Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque (1879). Mémoires de la vie de Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque, sieur de Soubise [by F. Viète ... (in French). Oxford University.

- Audiat, Louis (1868). Bernard Palissy: étude sur sa vie et ses travaux (in French). Didier et Cie.

- Revue des deux mondes. Tisch Library. Paris : [s.n.] 1879.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Sanchi, Luigi-Alberto (2006). Les Commentaires de la langue grecque de Guillaume Budé: l'œuvre, ses sources, sa préparation (in French). Librairie Droz. ISBN 978-2-600-01040-5.

- Marot, Clément; Héricault, Charles d' (1867). Oeuvres de Clément Marot (in French). Garnier frères.

- François Viète, Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque (1879). Mémoires de la vie de Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque, sieur de Soubise [by F. Viète ... (in French). Oxford University.

- Marot, Clément (1824). Oeuvres complètes de Clément Marot (in French). Rapilly.

- Revue des deux mondes. Tisch Library. Paris : [s.n.] 1879.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Lépinois, Ernest de Buchère de (1858). Histoire de Chartres (in French). Garnier.

- François Viète, Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque (1879). Mémoires de la vie de Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque, sieur de Soubise [by F. Viète ... (in French). Oxford University.

- François Viète, Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque (1879). Mémoires de la vie de Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque, sieur de Soubise [by F. Viète ... (in French). Oxford University.

- François Viète, Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque (1879). Mémoires de la vie de Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque, sieur de Soubise [by F. Viète ... (in French). Oxford University.

- Dupuy, Ernest (1970). Bernard Palissy (in French). Slatkine.

- Vester, Matthew Allen (2008). Jacques de Savoie-Nemours: l'apanage du Genevois au cœur de la puissance dynastique savoyarde au XVIe siècle (in French). Librairie Droz. ISBN 978-2-600-01211-9.

- de), Pierre de Bourdeille Brantôme (seigneur (1848). Œuvres complètes de Pierre de Bourdeille, abbé séculier de Brantôme et d'André vicomte de Bourdeille (in French). R. Sabe.

- Fillon, Benjamin (1864). L'art de terre chez les Poitevins, suivi d'une étude sur l'ancienneté de la fabrication du verre en Poitou (in French). L. Clouzot.

- Dupuy, Ernest (1970). Bernard Palissy (in French). Slatkine.

- Antoine de Bourbon, king of Navarre; Jeanne d'Albret, Queen of Navarre; Rochambeau, Eugène Achille Lacroix de Vimeur (1877). Lettres d'Antoine de Bourbon et de Jehanne d'Albret. Robarts – University of Toronto. Paris, Renouard.

- Duruy, George (November 2008). Le Cardinal Carlo Carafa (1519–1561): Etude Sur Le Pontificat De Paul IV (in French). BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-0-559-52343-4.

- "1469 – 1685 – Les Chevaliers de l'ordre de Saint-Michel en (...) – Histoire Passion – Saintonge Aunis Angoumois". www.histoirepassion.eu. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- Montluc, Blaise de Lasseran-Massencôme de (1836). Commentaires (in French). A. Desrez.

- François Viète, Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque (1879). Mémoires de la vie de Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque, sieur de Soubise [by F. Viète ... (in French). Oxford University.

- Dufaÿ, Bruno; Kisch, Yves de; Trombetta, Pierre-Jean; Paris-Poulain, Dominique; Roumégoux, Yves (1987). "L'atelier parisien de Bernard Palissy". Revue de l'Art. 78 (1): 33–60. doi:10.3406/rvart.1987.347668.

- Revue des deux mondes. Tisch Library. Paris : [s.n.] 1879.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Pannier, Jacques (1911). L'Église réformée de Paris sous Henri IV : rapports de l'église et de l'état, vie publique et privée des protestants, leur part dans l'histoire de la capitale, le mouvement des idées, les arts, la société, le commerce. Robarts – University of Toronto. Paris : H. Champion.

- Revue des deux mondes. Tisch Library. Paris : [s.n.] 1879.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Thou, Jacques-Auguste de (1734). Histoire universelle de Jacques-Auguste de Thou: depuis 1543. jusqu'en 1607 (in French).

- Petris, Loris; L'Hospital, Michel de (2002). La plume et la tribune: Michel de L'Hospital et ses discours (1559–1562) ; suivi de l'edition du De initiatione Sermo (1559) et des Discours de Michel de L'Hospital (1560–1562) (in French). Librairie Droz. ISBN 978-2-600-00646-0.

- Bondois, Paul-Marie (1923). "Henri Naëf. La conjuration d'Amboise et Genève. Genève, Paris, A. Jullien, Georg et Ed. Champion, 1922. – Lucien Romier. La conjuration d'Amboise ; l'aurore sanglante de la liberté de conscience ; le règne et la mort de François II. Paris, Perrin, 1923". Bibliothèque de l'École des chartes. 84 (1): 177–180.

- François Viète, Jules Bonnet (1879). Mémoires de la vie de Jean Parthenay-Larchevêque, sieur de Soubise: accompagnés le lettres ... (in French). University of Michigan. L. Willem.

- Revue des deux mondes. Tisch Library. Paris : [s.n.] 1879.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - "chapitre 2". larher.pagesperso-orange.fr. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- Dargaud, Jean Marie (1859). Histoire de la liberté religieuse en France et de ses fondateurs (in French). Charpentier.

- François Viète, Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque (1879). Mémoires de la vie de Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque, sieur de Soubise [by F. Viète ... (in French). Oxford University.

- "La Conjuration d'Amboise". Musée protestant. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- Revue des deux mondes. Tisch Library. Paris : [s.n.] 1879.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - François Viète, Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque (1879). Mémoires de la vie de Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque, sieur de Soubise [by F. Viète ... (in French). Oxford University.

- François Viète, Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque (1879). Mémoires de la vie de Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque, sieur de Soubise [by F. Viète ... (in French). Oxford University.

- "Le Massacre de Wassy (1er mars 1562)". Musée protestant. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- "Le massacre de Wassy (1562)". Musée protestant. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- Lorraine, Charles de; Lorraine), Charles de Guise (Cardinal de; Cuisiat, Daniel (1998). Lettres du cardinal Charles de Lorraine (1525–1574) (in French). Librairie Droz. ISBN 978-2-600-00263-9.

- Nauroy, Gérard (2004). L'écriture du massacre en littérature entre histoire et mythe: des mondes antiques à l'aube du XXIe siècle (in French). Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-03910-372-0.

- Germa-Romann, Hélène (2001). Du "bel mourir" au "bien mourir": le sentiment de la mort chez les gentilhommes français (1515–1643) (in French). Librairie Droz. ISBN 978-2-600-00463-3.

- François Viète, Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque (1879). Mémoires de la vie de Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque, sieur de Soubise [by F. Viète ... (in French). Oxford University.

- Soubise, Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque; Bonnet, Jules (1879). Mémoires de la vie de Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque, sieur de Soubise : accompagnés de lettres relatives aux guerres d'Italie sous Henri II et au Siège de Lyon (1562–1563). University of Ottawa. Paris : L. Willen.

- Revue des deux mondes. Tisch Library. Paris : [s.n.] 1879.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Haag, Eugène (1856). La France protestante: ou, Vies des protestants français qui se sont fait un nom dans l'histoire depuis les premiers temps de la réformation jusqu'à la reconnaissance du principe de la liberté des cultes par l'Assemblée nationale; ouvrage précéde d'une notice historique sur le protestantisme en France, suivi de pièces justificatives, et rédigé sur des documents en grand partie inédits (in French). J. Cherbuliez.

- Archives historiques et statistiques du département du Rhone (in French). J.M. Barret. 1827.

- François Viète, Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque (1879). Mémoires de la vie de Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque, sieur de Soubise [by F. Viète ... (in French). Oxford University.

- Soubise, Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque; Bonnet, Jules (1879). Mémoires de la vie de Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque, sieur de Soubise : accompagnés de lettres relatives aux guerres d'Italie sous Henri II et au Siège de Lyon (1562–1563). University of Ottawa. Paris : L. Willen.

- Revue des deux mondes. Tisch Library. Paris : [s.n.] 1879.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - François Viète, Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque (1879). Mémoires de la vie de Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque, sieur de Soubise [by F. Viète ... (in French). Oxford University.

- de), Pierre de Bourdeille Brantôme (seigneur (1848). Œuvres complètes de Pierre de Bourdeille, abbé séculier de Brantôme et d'André vicomte de Bourdeille (in French). R. Sabe.

- Parthenay-Gâtine, Communauté de communes. "Accueil". Communauté de communes Parthenay-Gâtine : Site Internet (in French). Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- Haag, Eugène (1856). La France protestante: ou, Vies des protestants français qui se sont fait un nom dans l'histoire depuis les premiers temps de la réformation jusqu'à la reconnaissance du principe de la liberté des cultes par l'Assemblée nationale; ouvrage précéde d'une notice historique sur le protestantisme en France, suivi de pièces justificatives, et rédigé sur des documents en grand partie inédits (in French). J. Cherbuliez.

- François Viète, Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque (1879). Mémoires de la vie de Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque, sieur de Soubise [by F. Viète ... (in French). Oxford University.

- Revue des deux mondes. Tisch Library. Paris : [s.n.] 1879.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Soubise, Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque; Bonnet, Jules (1879). Mémoires de la vie de Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque, sieur de Soubise : accompagnés de lettres relatives aux guerres d'Italie sous Henri II et au Siège de Lyon (1562–1563). University of Ottawa. Paris : L. Willen.

- François Viète, Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque (1879). Mémoires de la vie de Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque, sieur de Soubise [by F. Viète ... (in French). Oxford University.

- François Viète, Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque (1879). Mémoires de la vie de Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque, sieur de Soubise [by F. Viète ... (in French). Oxford University.

- Revue des deux mondes. Tisch Library. Paris : [s.n.] 1879.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Sanchi, Luigi-Alberto (2006). Les Commentaires de la langue grecque de Guillaume Budé: l'œuvre, ses sources, sa préparation (in French). Librairie Droz. ISBN 978-2-600-01040-5.

- François Viète, Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque (1879). Mémoires de la vie de Jean de Parthenay-Larchevêque, sieur de Soubise [by F. Viète ... (in French). Oxford University.

- Haag, Eugène; Haag, Émile (1856). La France protestante: ou, Vies des protestants français qui se sont fait un nom dans l'histoire depuis les premiers temps de la réformation jusqu'à la reconnaissance du principe de la liberté des cultes par l'Assemblée nationale; ouvrage précéde d'une notice historique sur le protestantisme en France, suivi de pièces justificatives, et rédigé sur des documents en grand partie inédits (in French). Genève.

- Dupuy, Ernest (1970). Bernard Palissy (in French). Slatkine.

- Varillas, Antoine (1684). Histoire de Charles IX (in French). Chez Thomas Amaulry.

- Varillas, Antoine (1684). Histoire de Charles IX (in French). Chez Thomas Amaulry.

- Bossuet, Jacques Bénigne (1836). Oeuvres complètes de Bossuet (in French). Outhenin-Chalandre fils.

- Bossuet, Jacques Bénigne (1836). Oeuvres complètes de Bossuet (in French). Outhenin-Chalandre fils.

- Biographie universelle, ancienne et moderne, ou, Histoire, par ordre alphabétique, de la vie publique et privée de tous les hommes qui se sont fait remarquer par leurs écrits, leurs actions, leurs talents, leurs vertus ou leurs crimes: ouvrage entièrement neuf (in French). Michaud frères. 1825.

- Paris, Société héraldique et généalogique de France (1879). Bulletin de la Société héraldique etʹgenéalogique de France (in French). Société héraldique & genéalogique de France.

- Annuaire de la noblesse de France (in French). Au Bureau de la publication. 1896.

- Brantôme), Pierre de Bourdeille (Sieur de; Bourdeille, vicomte André de (1838). Oeuvres complètes de Pierre de Bourdeille, abbé séculier de Brantôme et d'André, vicomte de Bourdeille (in French). A. Desrez.

- Collection universelle des mémoires particuliers relatifs à l'histoire de France: Contenant la suite des Mémoires de Michel de Castelnau : XVIe Siècle. 43 (in French). 1788.

- Bossuet, Jacques Bénigne (1836). Oeuvres complètes de Bossuet (in French). Outhenin-Chalandre fils.

- Jean-François), Dreux du Radier (M (1764). Mémoires historiques, critiques, et anecdotes de France ... (in French). Neaulme.

- Moréri, Louis (1740). Le grand dictionaire historique: ou, Le mélange curieux de l'histoire sacreé et profane (in French). Chez P. Brunel.

- Viète, François (1868). Introduction à l'art analytique (in French). Imprimerie des sciences mathematiques et physiques.

- Jean-Pierre Poirier, History of women of science in France: from the Middle Ages to the Revolution , Pygmalion/Gérard Watelet, 2002 (ISBN 2857047894), pp. 370–380.

- Bayle, Pierre (1820). Dictionnaire historique et critique de Pierre Bayle: Dictionnaire historique et critique (in French). Desoer.

- Archives historiques et statistiques du département du Rhone (in French). J.M. Barret. 1827.