Battle of Kiev (1941)

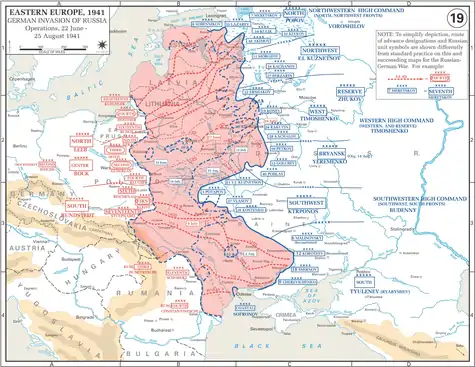

The First Battle of Kiev was the German name for the operation that resulted in a huge encirclement of Soviet troops in the vicinity of Kiev (present-day Kyiv) during World War II. This encirclement is considered the largest encirclement in the history of warfare (by number of troops). The operation ran from 7 July to 26 September 1941, as part of Operation Barbarossa, the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union.

| Battle of Kiev (1941) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Operation Barbarossa on the Eastern Front of World War II | |||||||||

Explosion of a Soviet radio-mine in Kiev (September 1941) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

25 infantry divisions 9 armoured divisions 544,000[1] | Initial 627,000[2] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

Total: 61,239[3] 12,728 killed 46,480 wounded 2,085 missing |

700,544 men[2]

343 aircraft destroyed[4] 28,419 guns and mortars lost[5] | ||||||||

Much of the Southwestern Front of the Red Army (commanded by Mikhail Kirponos) was encircled, but small groups of Red Army troops managed to escape the pocket days after the German panzers met east of the city, including the headquarters of Marshal Semyon Budyonny, Marshal Semyon Timoshenko and Commissar Nikita Khrushchev. Kirponos was trapped behind German lines and was killed while trying to break out.

The battle was an unprecedented defeat for the Red Army, exceeding even the Battle of Białystok–Minsk of June–July 1941. The encirclement trapped 452,700 soldiers, 2,642 guns and mortars, and 64 tanks, of which scarcely 15,000 had escaped from the encirclement by 2 October. The Southwestern Front suffered 700,544 casualties, including 616,304 killed, captured, or missing during the battle. The 5th, 37th, 26th, 21st, and 38th armies, consisting of 43 divisions, were almost annihilated and the 40th Army suffered many losses. Like the Western Front before it, the Southwestern Front had to be recreated almost from scratch.

Prelude

July

After the rapid progress of Army Group Centre through the central sector of the Eastern Front, a huge salient developed around its junction with Army Group South by late July 1941. On 7–8 July 1941, the German forces managed to break through the fortified Stalin Line, in the southeast portion of Zhytomyr Oblast, which ran along the 1939 Soviet border.[6] By 11 July 1941, the Axis ground forces reached the Dnieper tributary Irpin River (15–20 km (9.3–12.4 mi) to the west of Kiev).[6] The initial attempt to enter the city was thwarted by troops of the Kiev ukrep-raion (KUR, Kiev fortified district) and the counteroffensive of the Soviet 5th and 6th armies.[6] The advance on Kiev was halted and the main German effort then shifted towards the Korosten ukrep-raion, where the Soviet 5th Army was concentrated.[6] At the same time, the 1st Panzer Army was forced to transition to defense due to a counteroffensive of the Soviet 26th Army.[6] A substantial Soviet force, nearly the entire Southwestern Front, was positioned in and around Kiev, in the salient.[7][8] By the end of July, the Soviet front lost some of its units due to the critical situation of the Southern Front (the 6th and 12th armies) caused by the German 17th army.[6]

While lacking mobility and armor, due to high losses in tanks at the Battle of Uman,[8] on 3 August 1941,[6] they nonetheless posed a significant threat to the German advance and were the largest single concentration of Soviet troops on the Eastern Front at that time. Both the Soviet 6th and 12th armies were encircled at Uman, where some 102,000 Red Army soldiers and officers were taken prisoner.[6] On 30 July 1941, the German forces resumed their advance onto Kiev, with the German 6th army attacking positions between the Soviet 26th army and the Kiev ukrep-raion troops.[6]

August

On 7 August 1941, their advance was halted again by the Soviet 5th, 37th, and 26th armies, supported by the Pinsk Naval Flotilla.[6] With the help of the local population around the city of Kiev, anti-tanks ditches were dug and other obstacles were installed, including the establishment of 750 pillboxes and 100,000 mines planted along the 45 km (28 mi) frontline segment.[6] Some 35,000 soldiers were mobilized from local population along with some partisan detachments and two armored trains.[6]

On 19 July, Adolf Hitler had issued Directive No. 33, which cancelled the assault on Moscow in favor of driving south to complete the encirclement of Soviet forces surrounded in Kiev.[9] On 12 August 1941, Supplement to Directive No. 34 was issued. This directive represented a compromise between Hitler, who was convinced the correct strategy was to clear the salient occupied by Soviet forces on right flank of Army Group Center, in the vicinity of Kiev, before resuming the drive to Moscow, and Franz Halder, Fedor von Bock and Heinz Guderian, who advocated an advance on Moscow, as soon as possible. The compromise required 2nd and 3rd Panzer Groups of Army Group Centre, which were redeploying in order to aid Army Group North and Army Group South respectively, be returned to Army Group Centre, together with the 4th Panzer Group of Army Group North, once their objectives were achieved. Then the three Panzer Groups, under the control of Army Group Center, would lead the advance on Moscow.[10] Initially, Halder, chief of staff of the Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH), and Bock, commander of Army Group Center, were satisfied by the compromise, but soon their optimism faded as the operational realities of the plan proved too challenging.[11]

On 18 August, the OKH submitted a strategic survey (Denkschrift) to Hitler, regarding the continuation of operations in the East. The paper made the case for the drive to Moscow, arguing once again that Army Groups North and South were strong enough to accomplish their objectives without any assistance from Army Group Center. It pointed out that there was enough time left before winter to conduct only a single decisive operation against Moscow.[11]

On 20 August, Hitler rejected the proposal based on the idea that the most important objective was to deprive the Soviet Union of its industrial areas. On 21 August, Alfred Jodl of Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) issued a directive, which summarized Hitler's instructions, to Walther von Brauchitsch, commander-in-chief of the Army. The paper reiterated that the capture of Moscow, before the onset of winter, was not a primary objective. Rather, that the most important missions before the onset of winter were to seize the Crimea, and the industrial and coal region of the Don River; isolate the oil-producing regions of the Caucasus from the rest of the Soviet Union, and in the north, to encircle Leningrad, and link up with the Finns. Among other instructions, it also instructed that Army Group Center is to allocate sufficient forces to ensure the destruction of the "Russian 5th Army" and, at the same time, to prepare to repel enemy counterattacks in the central sector of its front.[12] Hitler referred to the Soviet forces in the salient collectively as the "Russian 5th Army".[13] Halder was dismayed, and later described Hitler's plan as "utopian and unacceptable", concluding that the orders were contradictory and Hitler alone must bear the responsibility for inconsistency of his orders and that the OKH can no longer assume responsibility for what was occurring; however, Hitler's instructions still accurately reflected the original intent of the Barbarossa directive of which the OKH was aware all along.[14] Gerhard Engel, in his diary for 21 August 1941, simply summarized it as, "it was a black day for the Army".[15] Halder offered his own resignation and advised Brauchitsch to do the same. Brauchitsch declined, stating Hitler would not accept the gesture, and nothing would change anyhow.[14] Halder withdrew his offer of resignation.

On 23 August, Halder convened with Bock and Guderian, in Borisov, in Belorussia, and afterwards flew with Guderian to Hitler's headquarters in East Prussia. During a meeting between Guderian and Hitler, with neither Halder nor Brauchitsch present, Hitler allowed Guderian to make the case for advancing on to Moscow, and then rejected his argument. Hitler claimed his decision to secure the northern and southern sectors of western Soviet Union were "tasks which stripped the Moscow problem of much of its significance" and was "not a new proposition, but a fact I have clearly and unequivocally stated since the beginning of the operation." Hitler also argued that the situation was even more critical because the opportunity to encircle the Soviet forces in the salient was "an unexpected opportunity, and a reprieve from past failures to trap the Soviet armies in the south."[14] Hitler also declared, "the objections that time will be lost and the offensive on Moscow might be undertaken too late, or that the armoured units might no longer be technically able to fulfil their mission, are not valid." Hitler reiterated that once the flanks of Army Group Center were cleared, especially the salient in the south, then he would allow the army to resume its drive on Moscow; an offensive, he concluded, which "must not fail".[15] Guderian returned to the 2nd Panzer Group and began the southern thrust in an effort to encircle the Soviet forces in the salient.[14]

The bulk of the 2nd Panzer Group and the 2nd Army were detached from Army Group Centre and sent south.[16] Its mission was to encircle the Southwestern Front, commanded by Semyon Budyonny, in conjunction with the 1st Panzer Group, of Army Group South, under Paul Ludwig Ewald von Kleist, which was advancing from a southeasterly direction.[17]

Following the crossing of the Dnieper river by German forces on 22 August 1941, the city of Kiev came under threat of encirclement. The command of the Southwestern Front appealed to the Stavka to allow for a withdrawal of forces from Kiev.[6]

September

The Red Army Chief of Staff, Boris Shaposhnikov, wrote a letter to the Southwestern Front on September 17, authorising a withdraw from Kiev, when the encirclement was already completed at Lokhvytsia, in Poltava region.[6]

Battle

The Panzer armies made rapid progress. On 12 September, Ewald von Kleist's 1st Panzer Group, which had by now turned north and crossed the Dnieper river, emerged from its bridgeheads at Cherkassy and Kremenchuk. Continuing north, it cut across the rear of Semyon Budyonny's Southwestern Front. On 16 September, it made contact with Guderian's 2nd Panzer Group, advancing south, at the town of Lokhvitsa, 120 mi (190 km) east of Kiev.[18] Budyonny was now trapped and soon relieved by Joseph Stalin's order of 13 September, and Budyonny was replaced by Semyon Timoshenko, in command of the Southwestern Direction.

After that, the fate of the encircled Soviet armies was sealed. With no mobile forces or supreme commander left, there was no possibility to effect a breakout. The infantry of the German 17th and 6th Armies, of Army Group South, soon arrived, along with the 2nd Army, also on loan from Army Group Center, and marching behind Guderian's tanks. They systematically began to reduce the pocket, assisted by the two Panzer armies. The encircled Soviet armies at Kiev did not give up easily. A savage battle in which the Soviets were bombarded by artillery, tanks, and aircraft had to be fought before the pocket had finally fallen.

By 19 September, Kiev had fallen, but the encirclement battle continued. After 10 days of heavy fighting, the last remnants of troops east of Kiev surrendered on 26 September. Several Soviet armies, namely the 5th, 37th, and 26th, were now encircled, as well as separate detachments of 38th and 21st armies.[6] The Germans claimed to have captured 600,000 Red Army soldiers (up to 665,000),[6] although these claims have included a large number of civilians suspected of evading capture.

During withdrawal from Kiev, on 20–22 September 1941, at Shumeikove Hai, near Dryukivshchyna, (today in Lokhvytsia Raion) several members of headquarters staff were killed, including Mikhail Kirponos (commander), Mykhailo Burmystenko (a member of military council), and Vasiliy Tupikov (chief of staff).[6] Some 15,000 Soviet troops managed to break through the encirclement.[6]

Aftermath

By virtue of Guderian's southward turn, the Wehrmacht destroyed the entire Southwestern Front east of Kiev during September. It inflicted nearly 700,544 casualties on the Red Army, while Soviet forces west of Moscow conducted many attacks on Army Group Centre. Although most of these attacks failed, the Soviet attacks in the Yelnya Offensive succeeded with the German forces abandoning the town, and resulted in the first major defeat for the Wehrmacht in Operation Barbarossa. With its southern flank secured, Army Group Center launched Operation Typhoon, in the direction of Vyazma, in October.

Over the objections of Gerd von Rundstedt, Army Group South was ordered to resume the offensive and overran nearly all of the Crimea and Left-bank Ukraine before reaching the edges of the Donbas industrial region. However, after four months of continuous operations, his forces were at the brink of exhaustion, and suffered a major defeat in the Battle of Rostov. Army Group South's infantry fared little better and failed to capture the vital city of Kharkov, before nearly all of its factories, skilled laborers, and equipment were evacuated east of the Ural Mountains.

Despite the order for wholesale destruction of Kiev issued in the Supplement to Directive 34 from 12 August,[19] the city was spared, to Hitler's fury, as there had been no fighting within.[20] The German troops, who occupied Kiev on 19 September, were surprised by a series of explosions from Soviet radio-mines in the city centre from 24 September onwards, the first of which also killed a number of local civilians reporting at the German Field Command to surrender outlawed items.[21][22] The resulting fire, which was not put out until 29 September, offered the Nazi authorities a pretext to commence the mass murder of Jews in Babi Yar on the same day.[23][24][25] As the city had not been razed, the German leadership launched the plan to starve it while officially attributing the food shortages to the consequences of Soviet economic policies.[26] Ultimately the implementation of the Hunger Plan in occupied Kiev was restrained by the fears of an uprising behind the lines,[27] and the city was only forcibly evacuated and subjected to widespread looting and burning during the German withdrawal in September–November 1943.[28]

Assessment

Immediately after World War II ended, prominent German commanders argued that had operations at Kiev been delayed, and had Operation Typhoon been launched in September, rather than October, the German Army would have reached and captured Moscow before the onset of winter.[29]

David Glantz argued that had Operation Typhoon been launched in September, it would have met greater resistance due to Soviet forces not having been weakened by their offensives east of Smolensk. The offensive would have also been launched with an extended right flank.[29] Glantz also claims that regardless of the final position of German troops when winter came, they would have still faced a counteroffensive by the 10 reserve armies raised by the Soviets toward the end of the year, who would also be better equipped by the vast industrial resources in the area of Kiev. Glantz asserts that had Kiev not been taken before the Battle of Moscow, the entire operation would have ended in a disaster for the Germans.[29]

See also

References

- G.K. Zhukov. Nhớ lại và suy nghĩ. tập 2. trang 99

- Glantz 1995, p. 293.

- "1941". Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- Krivosheev 1997, p. 260.

- Liedtke 2016, p. 148.

- Koval, M. The 1941 Kiev Defense Operation (КИЇВСЬКА ОБОРОННА ОПЕРАЦІЯ 1941). Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine

- Glantz 2011, pp. 54–55.

- Clark 1965, p. 130.

- Clark 1965, p. 101.

- Glantz 2011, p. 55.

- Glantz 2011, p. 56.

- Glantz 2011, p. 57.

- Glantz 2011, p. 60.

- Glantz 2011, p. 58.

- Glantz 2011, p. 59.

- Clark 1965, pp. 111, 139.

- Clark 1965, p. 133.

- Clark 1965, pp. 135, 141.

- Blau 1955, p. 64: "The attack on the city of Kiev proper was to be stopped; instead the city was to be annihilated by fire bombs and artillery shells as soon as a sufficient quantity of these means of destruction would become available. The Luftwaffe was to give every possible support to the ground forces."

- Berkhoff 2004, p. 29, 164: "On August 18, General Franz Haider described Hitler's order with regard to Kiev as a curt “Reduce to rubble.” The air force was supposed to do half of the job. In the end Kiev was not destroyed in this way, apparently because of a lack of bombs. Hitler was furious. One year later at the Werewolf, after saying that Petersburg had to be razed to the ground, he recalled how he had been “so enraged back then when the Air Force did not want to let Kiev have it. Sooner or later we must do it after all, for the inhabitants are coming back and want to govern from there.”"

- F-10 OBJECT RADIO-CONTROLLED MINE at shvachko.net: retrieved 30 November 2022

- Berkhoff 2004, p. 30.

- Snyder 2010, p. 201–202.

- Berkhoff 2004, p. 31–33.

- "Translation of Document 053-PS: The Deputy of the Reichs Ministry [Reichsministerium] for the occupied Eastern Provinces with the Army Group South Captain Dr. Koch, Report 10 (Concluded on 5 October 1941)", Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression, vol. 3, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1946, pp. 85–86,

The fire of Kiev (24-29 September 1941) destroyed the very center, that is the most beautiful and most representative part of the city with its two large hotels, the central Post Office, the radio station, the telegraph office and several department stores. An area of about 2 square kilometers was affected, some 50,000 people are homeless; they were scantily housed in abandoned quarters. As reconciliation for the obvious sabotage, the Jews of the city, approximately (according to figures from the SS Commands for commitment) 3500 [sic] people, half women, were liquidated on the 29th and 30th September. The population took the execution as much as they found out about it calmly, many with satisfaction; the newly vacated homes of the Jews were turned over for the relief of the housing shortage. Even if certain relief was created in a social respect, the care of the city of half a million is still in danger and one can already foresee food shortages and eventual epidemics.

- Berkhoff 2004, p. 164–168: "On November 4[, 1941], Economy Staff East replaced its September order. ... The new guidelines granted that one goal was “to assure the feeding of the population, as far as this is possible without influencing the German interests.” But great problems were supposedly unavoidable. After all, the “ruthless plundering and destruction by the Bolsheviks have very severely shaken the economic and trade life in the occupied territories. Need and misery are the unavoidable result for the native population, particularly in the major cities.” Propaganda should reiterate that only the Bolsheviks were responsible. Amounts of supplied food should “be kept as low as possible in the first period, to force the population to consume its own hoarded supplies and to prevent any influencing of the needs of the Armed Forces.” ... Lieutenant General Hans Leykauf, head of the food supply system for the Wehrmacht in the Reichskommissariat ... distributed in full agreement a November 29, 1941, report by an expert in army service that called the German policy in the Reichskommissariat tantamount to the “extermination” of “Jews, and the population of the large Ukrainian cities, which like Kiev do not receive any food.”".

- Epstein 2015, p. 142: "Hitler planned to wipe Soviet cities from the face of the earth. In May 1941 Herbert Backe, soon Reich minister of food, formulated a “Hunger Plan.” It foresaw starving some 30 million “useless eaters” in Soviet cities and diverting the food to German soldiers and civilians. In fall 1941, the Nazis lay siege to Leningrad, eventually killing 700,000 inhabitants, mostly from starvation (today, Leningrad is known by its pre-1914 name, St. Petersburg). Nazi administrators also tried to starve the Ukrainian cities of Kiev and Kharkiv. They never, however, fully implemented the Hunger Plan. They worried that it would spark too much resistance. They did not want to battle the Red Army and quell uprisings behind the front lines."

- Berkhoff 2004, p. 300–303: "On September 17, 1943, the German Army Group South ordered everyone to leave the large cities on the Dnieper. ... Then the inhabitants of the [Kiev] city center were ordered to vacate their homes within three days: the area became a forbidden zone, surrounded by barbed wire. Trespassers shall be shot on sight, it was stated, but even then locals (just as Germans and Hungarians did) dared to loot there. ... On September 25, there was an announcement on the radio that the city districts near the Dnieper – Pechersk, Lypky, Podil, and Stare Misto – also had to be vacated, by nine o’clock the next evening. (Later, two days were added to the deadline.) Thousands of Kievans moved their belongings by foot over long distances as fast as they could. The additions to the "military zone," which now comprised half of the city, were also looted. On October 21, anybody remaining anywhere in Kiev had to report to the train station. ... On November 5, German specialists dynamited Kiev's factories and power stations and set fire to some buildings."

- Glantz 2001, p. 23.

- Until 13 September

Sources

- Read, Anthony (2005). The Devil's Disciples: Hitler's Inner Circle. W W Norton & Co. ISBN 978-0-393-32697-0.

- Glantz, David (2001). The Soviet–German War 1941–1945: Myths and Realities: A Survey Essay. Archived from the original on 22 July 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- Clark, Alan (1965). Barbarossa: The Russian–German Conflict, 1941–45. London: William Morrow and Company.

- Glantz, David (2011). Barbarossa Derailed: The Battle for Smolensk, Volume 2. Birmingham: Helion & Company. ISBN 978-1-9060-3372-9.

- Glantz, David (1995). When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0899-7.

- Krivosheev, Grigori F. (1997). Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the Twentieth Century. London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 978-1-85367-280-4.

- Liedtke, Gregory (2016). Enduring the Whirlwind: The German Army and the Russo-German War 1941–1943. Helion and Company. ISBN 978-1-910777-75-6.

- Blau, George (1955), The German Campaign in Russia: Planning and Operations (1940-1942) (PDF), Washington, DC: Department of the Army

- Berkhoff, Karel C. (2004), Harvest of Despair: Life and Death in Ukraine under Nazi Rule, Cambridge, MA: Belknap, ISBN 978-0-674-01313-1

- Snyder, Timothy (2010), Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin, New York: Basic Books, ISBN 978-0-465-00239-9

- Epstein, Catherine (2015), Nazi Germany: Confronting the Myths, Chichester: Wiley, ISBN 978-1-118-29479-6

Further reading

- Erickson, John (1975). The Road to Stalingrad, Stalin's War with Germany. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-011141-0.

- Stahel, D. (2012). Kiev 1941: Hitler's Battle for Supremacy in the East. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01459-6.

External links

Freier, Thomas (2009). "10-Day Medical Casualty Reports". Human Losses in World War II. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012.