Red team

A red team is a group that pretends to be an enemy, attempts a physical or digital intrusion, then reports back to the organization so that the organization can improve their defenses. Red teams work for the organization or are hired by the organization. Their work is legal, but can surprise some employees who may not know that red teaming is occurring or who may be deceived by the red team. Red teams are used in several fields, including cybersecurity, airport security, law enforcement, the military, and intelligence agencies.

History

The concept of red teams has been around for a long time, initially used by the military for exercises and simulations to test and improve their own defenses. Over time, the practice of red teaming has expanded to other industries and organizations, including corporations, government agencies, and non-profit organizations. The approach has become increasingly popular in the world of cybersecurity, where red teams are used to simulate real-world attacks on an organization's digital infrastructure and test the effectiveness of their cybersecurity measures. The goal of a red team is to identify vulnerabilities and weaknesses in an organization's defenses before an actual attack occurs, so that they can be addressed and improved.[1]

Cybersecurity

Technical red teaming involves testing the digital security of an organization by attempting to infiltrate their computer networks digitally.

Pen testers, red teams, blue teams, purple teams

In cybersecurity, a penetration test involves ethical hackers ("pen testers") attempting to break into a computer system, with no element of surprise. The blue team (defending team) is aware of the penetration test and is ready to mount a defense.[2]

A red team goes a step further, and adds physical penetration, social engineering, and an element of surprise. The blue team is given no advance warning of a red team, and will treat it as a real intrusion.[2] One role of a permanent, in-house red team is to improve the security culture of the organization.[3]

Companies including Microsoft perform regular exercises in which both red and blue teams are used.[4]

A purple team is the temporary combination of both teams and can provide rapid information responses during a test.[5][6] One advantage of purple teaming is that the red team can launch certain attacks repeatedly, and the blue team can use that to set up detection software, calibrate it, and steadily increase detection rate.[7] Purple teams may engage in "threat hunting" sessions, where both the red team and the blue team look for real intruders. Involving other employees in the purple team is also beneficial, for example software engineers who can help with logging and software alerts, and managers who can help identify the most financially damaging scenarios.[8] One danger of purple teaming is complacence and the development of groupthink, which can be combatted by hiring people with different skillsets or hiring an external vendor.[9]

Attack

The initial entry point of a red team or an adversary is called the beachhead. A mature blue team should be adept at finding the beachhead and evicting the attackers. In fact, a role of the red team is to increase the skills of the blue team.[10]

When infiltrating, there is a stealthy "surgical" approach that stays under the radar of the blue team and requires a clear objective, and a noisy "carpet bombing" approach that is more like a brute force attack. Carpet bombing is often the more useful approach for red teams, because it can discover unexpected vulnerabilities.[11]

There are "traditional" attack vectors such as obtaining domain controller administration credentials, and also newer attack vectors such as cryptocurrency mining, too much employee access to personally identifiable information (PII) which opens the company up to General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) fines, and targeted social media advertising.[12] Tabletop exercises can be used to simulate intrusions that are too expensive, too complicated, or illegal to execute live.[13] It can be useful to attempt intrusions against the red team and the blue team, in addition to more traditional targets.[14]

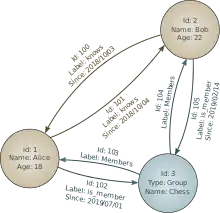

Once access to a network is achieved, reconnaissance can be conducted. The data gathered can be placed in a graph database, which is software that visually plots nodes, relationships, and properties. Typical nodes might be computers, users, or permission groups.[15] Red teams will typically have very good graph databases of their own organization, because they can utilize home-field advantage, including working with the blue team to create a thorough map of the network, and a thorough list of users and administrators.[16] A query language such as Cypher can be used to create and modify graph databases.[17] Any type of administrator is valuable to place in the graph database, including administrators of third party tools such as Amazon Web Services (AWS).[18] Data can sometimes be exported from tools and then inserted into the graph database.[19]

Once the red team has compromised a computer, website, or system, a powerful technique is credential hunting. Credentials are anything that grants you access to something. These can be in the form of clear text passwords, ciphertext, hashes, or access tokens. The red team gets access to a computer, looks for credentials that can be used to access a different computer, then this is repeated, with the goal of accessing many computers.[20] Credentials can be stolen from many locations, including files, source code repositories such as Git, computer memory, and tracing and logging software. Techniques such as pass the cookie and pass the hash can be used to get access to websites and machines without entering a password. Techniques such as optical character recognition (OCR), exploiting default passwords, spoofing a credential prompt, and phishing can also be used.[21]

The red team can utilize computer programming and command-line interface (CLI) scripts to automate some of their tasks. For example, command-line interface (CLI) scripts can utilize the Component Object Model (COM) on Microsoft Windows machines in order to automate tasks in Microsoft Office applications. Useful tasks might include sending emails, searching documents, encrypting, or retrieving data. Red teams can take control of a browser using Internet Explorer's COM, Google Chrome's remote debugging feature, or the testing framework Selenium.[22]

Defense

During a real intrusion, the red team can be repurposed to work with the blue team to help with defense. Specifically, they can provide analysis of what the intruders will likely try to do next. During an intrusion, both the red team and the blue team have a home-field advantage because they are more familiar with the organization's networks and systems than the intruder.[7]

An organization's red team may be an attractive target for real attackers. Red team member's machines may contain sensitive information about the organization. This should be taken into account, and red team member's machines secured.[23] Techniques for securing machines include configuring the operating system's firewall, restricting Secure Shell (SSH) and Bluetooth access, improving logging and alerts, securely deleting files, and encrypting hard drives.[24]

It can sometimes be worthwhile to engage in "active defense", which includes setting up decoys and honeypots to help track the location of intruders.[25] Various software can be used to set up a honeypot file depending on the operating system: macOS tools include OpenBMS, Linux tools include auditd plugins, and Windows tools include System Access Control Lists (SACL). Notifications can include popups, emails, and writing to a log file.[26] Centralized monitoring, where important log files are quickly sent to logging software on a different machine, is a useful network defense technique.[27]

Managing a red team

The use of rules of engagement can help to delineate which systems are off-limits, prevent security incidents, and ensure that employee privacy is respected.[28] The use of a standard operating procedure (SOP) can ensure that the proper people are notified and involved in planning, and improve the red team process, making it mature and repeatable.[29] Red team activities should have a regular rhythm.[30]

Tracking certain metrics or key performance indicators (KPIs) can help to make sure a red team is achieving the desired output. Examples of red team KPIs include performing a certain number of penetration tests per year, or by growing the team by a certain number of pen testers within a certain time period. It can also be useful to track the number of compromised machines, compromisable machines, and other metrics related to infiltration. These statistics can be graphed by day and placed on a dashboard displayed in the security operations center (SOC) to provide motivation to the blue team to detect and close breaches.[31] In order to identify worst offenders, compromises can be graphed and grouped by where in the software they were discovered, company office location, job title, or department.[32] Monte Carlo simulations can be used to identify which intrusion scenarios are most likely, most damaging, or both.[33] A Test Maturity Model, a type of Capability Maturity Model, can be used to assess how mature a red team is, and what the next step is to grow.[34] The MITRE ATT&CK Navigator, a list of tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) including advanced persistent threats (APTs), can be consulted to see how many TTPs a red team is exploiting, and give additional ideas for TTPs to utilize in the future.[35]

Physical intrusion

Physical red teaming or physical penetration testing[36] involves testing the physical security of a facility, including the security practices of its employees and security equipment. Examples of security equipment include security cameras, locks, and fences. Unlike cybersecurity red teaming, computer networks are not usually the target.[37] Unlike cybersecurity, which typically has many layers of security, there may only be one or two layers of physical security present.[38]

Having a "rules of engagement" document that is shared with the client is helpful, to specify which tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) will be used, what locations may be targeted, what may not be targeted, how much damage to equipment such as locks and doors is permitted, what the plan is, what the milestones are, and sharing contact information.[39][40] The rules of engagement may be updated after the reconnaissance phase, with another round of back and forth between the red team and the client.[41] The data gathered during the reconnaissance phase can be used to create an operational plan, both for internal use, and to send to the client for approval.[42]

Reconnaissance

Part of physical red teaming is performing reconnaissance.[43] The type of reconnaissance gathered usually includes information about people, places, security devices, and weather.[44] Reconnaissance has a military origin, and military reconnaissance techniques are applicable to physical red teaming. Red team reconnaissance equipment might include military clothing since it does not rip easily, red lights to preserve night vision and be less detectable, radios and earpieces, camera and tripod, binoculars, night vision equipment, and an all-weather notebook.[45] Some methods of field communication include a Bluetooth earpiece dialed into a cell phone conference call during the day, and two-way radios with earpieces at night.[46] In case of compromise, each red team member should carry identification and an authorization letter with multiple after-hours contacts who can vouch for the legality and legitimacy of the red team's activities.[47]

Before physical reconnaissance occurs, open-source intelligence (OSINT) gathering can occur by researching locations and staff members via the Internet, including the company's website, social media accounts, search engines, mapping websites, and job postings (which give hints about the technology and software the company uses).[48] It is a good practice to do multiple days of reconnaissance, to reconnoiter both during the day and at night, to bring at least three operators, to utilize a nearby staging area that is out of sight of the target, and to do reconnaissance and infiltration as two separate trips rather than combining them.[49]

Recon teams can use techniques to conceal themselves and equipment. For example, a passenger van can be rented and the windows can be blacked out to conceal photography and videography of the target.[50] Examining and videoing the locks of a building during a walk-around can be concealed by the recon pretending to be on the phone.[51] In the event of compromise, such as employees becoming suspicious, a story can be rehearsed ahead of time until it can be recited confidently. If the team has split up, the compromise of one operator should result in the team leader pulling the other operators out.[52] Concealed video cameras can be used to capture footage for later review, and debriefs can be done quickly after leaving the area so that fresh information is quickly documented.[53]

Infiltration

Most physical red team operations occur at night, due to reduced security of the facility and so that darkness can conceal activities.[54] An ideal infiltration is usually invisible both outside the facility (the approach is not detected by bystanders or security devices) and inside the facility (no damage is done and nothing is bumped or left out of place), and does not alert anyone that a red team was there.[55]

Preparation

The use of a "load out list" can help ensure that important red team equipment is not forgotten.[56] The use of military equipment such as MOLLE vests and small tactical bags can provide useful places to store tools, but has the downsides of being conspicuous and increasing encumbrance.[57] Black clothing or dark camouflage can be helpful in rural areas, whereas street clothes in shades of gray and black may be preferred in urban areas.[58] Other urban disguise items include a laptop bag, or a pair of headphones around the neck.

Approach

Light discipline (keeping lights from vehicles, flashlights, and other tools to a minimum) reduces the chance of compromise.[59] A single vehicle rather than a convoy of vehicles, and a vehicle with exterior lights turned off, is less conspicuous. The use of red lights, for example red flashlights, can help reduce the visibility of lights.

Sometimes there are security changes between reconnaissance and infiltration, so it is a good practice for teams that are approaching a target to "assess and acclimate", to see if any new security measures can be seen.[60] Compromises during infiltration are most likely to occur during the approach to the facility.[61] Employees, security, police, and bystanders are the most likely compromise a physical red team.[62] Bystanders are rarer in rural areas, but also much more suspicious.[63]

Proper movement can help a red team avoid being spotted while approaching a target, and may include rushing, crawling, avoiding silhouetting when on hills, walking in formations such as single file, and walking in short bursts then pausing.[64] The use of hand signals may be used to reduce noise.[65]

Entering the facility

Common security devices include doors, locks, fences, alarms, motion sensors, and ground sensors. Doors and locks often faster and quieter to bypass with tools and shims, rather than lock picking.[66] RFID locks are common at businesses, and covert RFID readers combined with social engineering during reconnaissance can be used to duplicate an authorized employee's badge.[67] Barbed wire on fences can be bypassed by placing a thick blanket over it.[68] Anti-climb fences can be bypassed with ladders.[69] Alarms can sometimes be neutralized with a radio jammer that targets the frequencies that alarms use for their internal and external communications.[70] Motion sensors can be defeated with a special body-sized shield that blocks a person's heat signature.[71] Ground sensors are prone to false positives, which can lead security personnel to not trust them or ignore them.[72]

Inside the facility

Once inside, if there is suspicion that the building is occupied, disguising oneself as a cleaner or employee using the appropriate clothing is a good tactic.[73] Noise discipline is often important once inside a building, as there are less ambient sounds to mask red team noises.[74]

Red teams usually have a specific location and task pre-planned for each team or team member, such as finding the server room and doing things in there. However, it can be difficult to figure out the room's location in advance, so this is often figured out on the fly. Reading emergency exit route signs and the use of a watch with a compass can assist with navigating inside of buildings.[75]

Commercial buildings will often have some lights left on. It is good practice to not turn lights on or off, as this may alert someone. Instead, utilizing already unlit areas is preferred for red team operations, with rushing and freezing techniques to be used to quickly move through illuminated areas.[76] Standing full-height in front of windows and entering buildings via lobbies should be avoided due to the risks of being seen.[77]

A borescope can be used to peer around corners and under doors, to help spot people, cameras, or motion detectors.[78]

Once the target room has been reached, if something needs to be found such as a specific document or specific equipment, the room can be divided into sections, with each red team member focusing on a section.[79]

Red teaming by organization

Military

In military wargaming, the opposing force (or OPFOR) in a simulated conflict may be referred to as a Red Cell; this is an interchangeable term for red team. The key theme is that the adversary (red team) leverages tactics, techniques, and equipment as appropriate to emulate the desired actor. The red team challenges operational planning by playing the role of a mindful adversary. In United States wargaming simulations, the U.S. force is always the blue team, whereas the opposing force is always the red team.

Intelligence community

When applied to intelligence work, red-teaming is sometimes called alternative analysis.[80]

United States government

Army

In the US Army, red-teaming is defined as a "structured, iterative process executed by trained, educated and practiced team members that provides commanders an independent capability to continuously challenge plans, operations, concepts, organizations and capabilities in the context of the operational environment and from our partners' and adversaries' perspectives."[81]

Directed Studies Office

Red teams were used in the United States Armed Forces much more frequently after a 2003 Defense Science Review Board recommended them to help prevent the shortcomings that led to the September 11 attacks. The U.S. Army created the Army Directed Studies Office in 2004. This was the first service-level red team, and until 2011 was the largest in the Department of Defense (DoD).[82]

University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies (UFMCS)

The University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies provides courses for red team members and leaders. Most resident courses are conducted at Fort Leavenworth and target students from U.S. Army Command and General Staff College (CGSC) or equivalent intermediate and senior level school.[83] Courses include topics such as critical thinking, groupthink mitigation, cultural empathy and self-reflection.[84]

Marine Corps

The Marine Corps red-team concept commenced in March 2011 when the Commandant of the Marine Corps (CMC) General James F. Amos drafted a white paper titled, Red Teaming in the Marine Corps. In this document, Amos discussed how the concept of the red team needs to challenge the process of planning and making decisions by applying critical thinking from the tactical to strategic level. He also tasked senior leadership in the Marine Corps to transition the red-teaming from a paper concept into real practice. This meant establishing the personnel requirements at the following Marine organizations: Marine Expeditionary Force (MEF), Marine Expeditionary Brigade (MEB), CMC Strategic Initiatives Group (SIG), Marine Corps University (MCU), and MAGTF Staff Training Program (MSTP).

In June 2013, the Marine Corps staffed the red-team billets outlined in the draft white paper. In the Marine Corps, all Marines designated to fill red-team positions have to complete either the six-week or nine-week red-team training courses provided by the University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies (UFMCS). MCU was tasked to have a core of qualified red-team instructors to develop red-teaming curriculum, methodologies, and doctrine, and to teach at the Marine Corps resident Professional Military Education (PME) institutions.[85]

The Marine Corps had to provide a Marine officer to be part of the UFMCS instructor staff. LtCol Will Rasgorshek was the first Marine qualified as a red-team instructor at UFMCS teaching the various red-team courses offered at UFMCS. LtCol Brian McDermott was one of the first red-team instructors at MCU.

The MCU Red Team develops curriculum, teaches, and supports major academic planning exercises at the following resident MCU institutions: Senior SNCO Academy, Expeditionary Warfare School, Marine Corps Command and Staff College, Marine Corps War College, and School of Advanced Warfighting. In addition, the MCU Red Team supports the USMC Command and Staff blended seminar, the Marine Corps annual Title X wargame, and other wargames as directed by Marine Corps Combat Development Command.

In the summer of 2015, the USMC Military Occupational Specialty Manual stated that any Marine who successfully completed the UFMCS Red Team 6- or 9-week course would be authorized the additional military occupational specialty (AMOS) of 0506. In December 2015, the Marines codified the red-team concept into doctrine by incorporating red-team training and readiness requirements developed by the initial red team members at MCU, MSTP, and SIG. The five requirements currently reside in NAVMC 3500.108A, chapter 3: "Marine Air Ground Task Force Planner Training and Readiness Manual".[86]

The mission of Marine Corps red teams is to "provide the Commander an independent capability that offers critical reviews and alternative perspectives that challenge prevailing notions, rigorously test current Tactics, Techniques and Procedures, and counter group think in order to enhance organizational effectiveness."[87]

Department of Defense

The United States Department of Defense (DoD) uses cyber red teams to conduct adversarial assessments on their own networks.[88] These red teams are certified by the National Security Agency and accredited by the United States Strategic Command.[88] This certification and accreditation allows these red teams to conduct adversarial assessments on DoD operational networks, testing implemented security controls and identifying vulnerabilities of information systems. These cyber red teams are the "core of the cyber OPFOR".[89]

Federal Aviation Administration

The FAA has been implementing red teams since Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland. Red teams conduct tests at about 100 US airports annually. Tests were on hiatus after September 11, 2001 and resumed in 2003 under the Transportation Security Administration, who assumed the FAA's aviation security role after 9/11.[90]

Before the September 11th attacks, FAA use of red-teaming had revealed severe weaknesses in security at Logan International Airport in Boston, where two of the four hijacked 9/11 flights originated. Some former FAA investigators who participated on these teams feel that the FAA deliberately ignored the results of the tests, and that this resulted in part in the 9/11 terrorist attack on the US.[91]

Transportation Security Administration

The Transportation Security Administration has used red-teaming in the past. An analysis of some red-team operations discovered that undercover agents were able to fool Transportation Security Officers and bring deadly weapons through security at some major airports at least 70% of the time.[92]

See also

References

- "What is red teaming?". WhatIs.com. Retrieved 2023-05-14.

- "Penetration Testing Versus Red Teaming: Clearing the Confusion". Security Intelligence. Retrieved 2020-12-23.

- Rehberger, p. 3

- "Microsoft Enterprise Cloud Red Teaming" (PDF). Microsoft.com.

- "The Difference Between Red, Blue, and Purple Teams". Daniel Miessler. Retrieved 2022-04-03.

- "What is Purple Teaming? How Can it Strengthen Your Security?". Redscan. 2021-09-14. Retrieved 2022-04-03.

- Rehberger, p. 66

- Rehberger, p. 68

- Rehberger, p. 72

- Rehberger, pp. 40–41

- Rehberger, p. 44

- Rehberger, p. 117

- Rehberger, p. 132

- Rehberger, p. 127

- Rehberger, p. 140

- Rehberger, p. 138

- Rehberger, p. 165

- Rehberger, p. 178

- Rehberger, p. 180

- Rehberger, p. 203

- Rehberger, p. 245

- Rehberger, p. 348

- Rehberger, p. 70

- Rehberger, p. 349

- Rehberger, pp. 70–71

- Rehberger, p. 447

- Rehberger, p. 473

- Rehberger, p. 23

- Rehberger, p. 26

- Rehberger, p. 73

- Rehberger, pp. 93–94

- Rehberger, pp. 97–100

- Rehberger, p. 103

- Rehberger, p. 108

- Rehberger, p. 111

- Talamantes, pp. 24–25

- Talamantes, pp. 26–27

- Talamantes, p. 153

- Talamantes, p. 41

- Talamantes, p. 48

- Talamantes, p 110

- Talamantes, pp. 112–113

- Talamantes, p. 51

- Talamantes, p. 79

- Talamantes, pp. 58–63

- Talamantes, p. 142

- Talamantes, pp. 67–68

- Talamantes, p. 83

- Talamantes, pp. 72–73

- Talamantes, pp. 89–90

- Talamantes, p. 98

- Talamantes, pp. 100–101

- Talamantes, p. 102

- Talamantes, p. 126

- Talamantes, p. 136

- Talamantes, p. 137

- Talamantes, pp. 133–135

- Talamantes, p. 131

- Talamantes, p. 126

- Talamantes, p. 153

- Talamantes, p. 160

- Talamantes, p. 173

- Talamantes, p. 169

- Talamantes, pp. 183–185

- Talamantes, p. 186

- Talamantes, p. 215

- Talamantes, p. 231

- Talamantes, p. 202

- Talamantes, p. 201

- Talamantes, p. 213

- Talamantes, p. 208

- Talamantes, p. 199

- Talamantes, p. 238

- Talamantes, p. 182

- Talamantes, pp. 242–243

- Talamantes, p. 247

- Talamantes, p. 246

- Talamantes, p. 249

- Talamantes, p. 253

- Mateski, Mark (June 2009). "Red Teaming: A Short Introduction (1.0)" (PDF). RedTeamJournal.com. Retrieved 2011-07-19.

- "TRADOC News Service". Tradoc.army.mil. Archived from the original on 2011-06-17. Retrieved 2011-07-19.

- Mulvaney, Brendan S. (July 2012). "Strengthened Through the Challenge" (PDF). Marine Corps Gazette. Marine Corps Association. Retrieved October 23, 2017 – via HQMC.Marines.mil.

- "UFMCS Course Enrollment".

- "University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies Courses". army.mil. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- Amos, James F. (March 2011). "Red Teaming in the Marine Corps".

- "3: Marine Air Ground Task Force Planner Training and Readiness Manual Change 3" (PDF). NAVMC 3500.108A. 23 December 2015 – via Marines.mil.

- Broderick, Brian (July 2012). "Does the Marine Corps Need Red Teams? Accepting Contrarian Viewpoints". Marine Corps Gazette. Marine Corps Association – via MCA-Marines.org.

- "Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Manual 5610.03" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-01. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- "Cybersecurity" (PDF). Operational Test & Evaluation Office of the Secretary of Defense. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- Sherman, Deborah (30 March 2007). "Test devices make it by DIA security". Denver Post.

- "National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States". govinfo.library.unt.edu. University of North Texas. Retrieved 2015-10-13.

- http://abclocal.go.com/ktrk/story?section=news/local&id=7848683

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from Army Approves Plan to Create School for Red Teaming. United States Army.

This article incorporates public domain material from Army Approves Plan to Create School for Red Teaming. United States Army.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies. United States Army.

This article incorporates public domain material from University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies. United States Army.

Bibliography

Further reading

- Ministry of Defence - Red Teaming Handbook v3

- The Red Team Handbook - The Army's Guide to Making Better Decisions v9.0

- "Don't Box in the Red Team", Armed Forces Journal

- FAA Red Team leader Bogdan Dzakovic's report to the 911 commission

- GAO Red Team reveals Nuclear material can easily be smuggled into the United States years after 911 attack

- Red Team Final Report

- Officers With PhDs Advising War Effort

- "Reflections from a Red Team Leader", from Military Review

- Defense Science Board – Task Force on the Role and Status of DoD Red Teaming Activities

- A Guide to Red Teaming, DCDC, UK

- Defining and Categorizing a Red Team