Third Front (China)

The Third Front Movement (Chinese: 三线建设; pinyin: Sānxiàn jiànshè) or Third Front Construction was a Chinese government campaign to develop industrial and military facilities in the country's interior.[1]: 44 The campaign was motivated by concerns that China's industrial and military infrastructure would be vulnerable in the event of invasion by the Soviet Union or air raids by the United States.[1]: 49 The largest development campaign of Mao-era China, it involved massive investment in national defense, technology, basic industries (including manufacturing, mining, metal, and electricity), transportation and other infrastructure investments.

.jpg.webp)

"Third Front" is a geo-military concept: it is relative to the "First Front" area that is close to the potential war fronts. The Third Front region covers 13 provinces and autonomous regions with its core area in the Northwest (including Shaanxi, Gansu, Ningxia, and Qinghai) and Southwest (including nowadays Sichuan, Chongqing, Yunnan, and Guizhou). It was motivated by national defense considerations, most noticeably the escalation of the Vietnam War after the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, the Sino-Soviet Split and small-scale border skirmishes between the two countries.

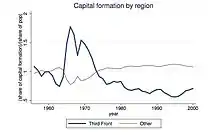

While based on national defense considerations, the Third Front Movement in fact industrialized part of China’s most interior and agricultural region. The area of the Third Front is the hardest part of China for any invading foreign power to access. During the Second Sino-Japanese War of 1937–45, it remained unconquered. The Kuomintang, at that time in alliance with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in the Second United Front, made Chongqing their capital. Some Chinese industry was also moved there from the cities. So while the 'Third Front' strategy had precedents, the scale of the Third Front Movement was far larger than the one initiated by the Kuomintang. The relative size of the Third Front Movement (as a share of the total national investments) was also larger than the China Western Development Movement initiated in 2001. Between 1964 and 1980, China invested 205 billion yuan in the Third Front Region, accounting for 39.01% of total national investment in basic industries and infrastructure. Millions of factory workers, cadres, intellectuals, military personnel, and tens of millions of construction workers, flocked to the Third Front region. More than 1,100 large and medium-sized projects were established during the Third Front period. With large projects such as Chengdu-Kunming Railway, Panzhihua Iron and Steel, Second Auto Works, the Third Front Movement stimulated previously poor and agricultural economies in China’s southwest and northwest. Dozens of cities, such as Mianyang, Deyang, Panzhihua in Sichuan, Guiyang in Guizhou, Shiyan in Hubei, emerged as major industrial cities. However, the designs of many Third Front projects were deficient. For national defense reasons, location choices for the Third Front projects followed the guiding principle “Close to mountains, dispersed, hidden” (kaoshan, fensan, yinbi). Many Third Front projects were located in remote areas that were hard to access. Many of them were far away from supplies and potential markets. The Third Front Movement was carried out in a hurry. Many Third Front projects were simultaneously being designed, constructed, and put in production, (biansheji, bianshigong, bianshengchan). The degree of inefficiency was egregious. Since the mid-1970s, government subsidies gradually dwindled. Since the reform of state-owned enterprises starting in the 1980s, many Third Front plants went bankrupt. Yet some others reinvented themselves and continued to serve as pillars in their respective local economies.

Definition

Mao created the concept of the Third Front to locate critical infrastructure and national defense facilities away from areas where they would be vulnerable to invasions.[1]: 177 Describing the geographical foundation of the concept, he stated:[1]: 177

Our first front is coastal regions, second front is the line that cuts from Baotou to Lanzhou and southwest is the third front ... in the period of the atomic bomb, we need a strategic rear for retreat, and we should be prepared to go into the mountains [to become guerilla]. We need a place like this.

The "Third Front" included three provinces in the Southwest (Sichuan, including today’s Chongqing, Yunnan, and Guizhou), three provinces and one ethnical autonomous region in the Northwest (Shaanxi, Qinghai, eastern part of Gansu, Ningxia), parts of Hebei, Henan, and Hunan that are to the west of the Beijing-Guangzhou Railway, and Northwest Guangxi and South Shanxi. The rest of China between the First Front and the Third Front was called the Second Front; the vast area between provinces on the First Front and the Beijing-Guangzhou Railway. The Second Front includes Anhui, Jiangxi and east parts of Hebei, Henan, Hubei, Hunan. Among the Third Front region, Guizhou, the mountainous East Sichuan, Sichuan Basin, South Shaanxin (Hanzhong and the northern piedmont of the Qin Mountains) attracted the most firms, research institutes, and workers due to the Third Front Movement. Panzhihua in Sichuan and Jiuquan in Gansu hosted new steel industries. Sichuan and Longxi County, Gansu has clusters of mining firms for nonferrous metals. Coal mining firms were scattered across Sichuan, Yunnan, Guizhou, Gansu, Qinghai, Shaanxi. Hydropower stations were built on the upper reaches of the Yangtze River and the Yellow River, while new large-scale thermal power stations were built in cities such as Baoji in Shaanxi, Guiyang in Guizhou. Machinery plants were mainly located in Sichuan and Guizhou. Chengdu in Sichuan received many plants producing electronic devices and airplanes. Mianyang and Guangyuan received many plants in the nuclear industry and the electronic industries. Chongqing is a center for conventional weapons, producing rifles, tanks, trucks, and conventional powered submarines. Guiyang formed a cluster of photo-electricity plants. Anshun has a new cluster of airplane plants. Some of these firms in the Third Front were relocated from the First Front and the Second Front regions, yet many more were newly built.

The aforementioned Third Front region was under direct leadership of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China, thus is also called the “Big Third Front”. In contrary, “Small Third Front” regions include the mountainous and rear parts of each province in the First and Second Front. Provincial level governments led the industrialization of these regions. Plants that produce conventional weapons, basic industries were moved to or newly built in these regions. The purpose of the construction of the Small Third Front is to make individual provinces capable of self-defense in the event of war. Many Small Third Front regions were previously Communist-controlled regions during the Republican era and the Chinese Civil War with the Nationalist China.

Process

Prior to the Third Front construction, the fourteen largest cities in China's potentially vulnerable regions included approximately 60% of the country's manufacturing, 50% of its chemical industries, and 52% of its national defense industries.[1]: 177 In particular, the northeast was China's industrial center.[1]: 177 China's population centers were concentrated in eastern coastal areas where they would be vulnerable to attack by air or water.[1]: 177 In constructing the Third Front, China built a self-sufficient base industrial base area as a strategic reserve in the event of war with the Soviet Union or the United States.[2]: 1 The campaign was centrally planned.[2]: 37

Between 1964 and 1980, more than 1,100 large and medium-sized projects were established in the Third Front region. Major universities, including both Tsinghua University and Peking University, opened campuses in Third Front cities.[1]: 179 Operating on the principle of "choose the best people and best horses for the Third Front," (好人好马上三线; hǎorén hǎomǎ shàngsānxiàn) many skilled engineers, scientists, and intellectuals were transferred to Third Front facilities.[1]: 179 In this slogan, the "best horses" refers to the best available equipment and resources.[2]: 80 Third Front construction methods fused both low-tech and high-tech techniques.[2]: 37

Background

After the failure of the Great Leap Forward, China's leadership slowed the pace of industrialization.[2]: 3 It invested more on in China's coastal regions and focused on the production of consumer goods.[2]: 3 Construction of the Third Front reversed these trends, developing industry and using mass mobilization for the construction of such industrial projects, an approached that had been suspended after the failures of the Great Leap Forward.[2]: 9

In February 1962, Chen Yun had proposed that the Third Five-Year Plan should “solve the problems of food, clothes, and other life necessities” (jiejue chichuanyong). Zhou Enlai, in his report of the State Council on March 28, also reported that “[the government] should put agriculture in the primary place of the nation’s economy. The economic planning should follow the priorities such that agriculture comes first, light industries comes next, heavy industries have the lowest priority”. In early 1963, a central planning team (led by Li Fuchun, Li Xiannian, Tan Zhenlin, Bo Yibo) put “solving the problems of food, clothes, and other life necessities” (解决人民的吃穿用) as the priority of economic works in their proposal for the Third Five-Year Plan. The preliminary draft for the Third Five Year Plan, of which Deng Xiaoping was a major author, had no provision for largescale industrialization in the country's interior.[2]: 29

Mao objected to the preliminary proposal because ”[t]he Third Five-Year Plan […] need[s] to set basic industries in the Southwest.” He said that agricultural and defense industries are like fists, basic industries are like the hip. “The fists cannot be powerful unless the hip is well seated.” According to Mao’s judgment, there was possibility that China would be involved in a war, while China’s population and industries were concentrated on the east coast. As one of his inspirations for the Third Front, Mao cited the negative example of Chiang Kai-Shek's failure to establish sufficient industry away from the coast prior to the Second Sino-Japanese war, resulting in the Nationalist government being forced to retreat to a small inland industrial base in the face of Japanese invasion.[2]: 24

In April 1964, Mao read a General Staff report commissioned by deputy chief Yang Chengwu[2]: 54 which evaluated the distribution of Chinese industry, noted that they were primarily concentrated in 14 major coastal cities which were vulnerable to nuclear attack or air raids, and recommended that the General Staff research measures to guard against a sudden attack.[2]: 4 Major transportation hubs, bridges, ports and some dams were close to these major cities. Destruction of these infrastructures could lead to disastrous consequences. This evaluation prompted Mao to advocate for the creation of a heavy industrial zone as a safe haven for retreat in the event of foreign invasion during State Planning Meetings in May 1964.[2]: 4 Subsequently referred to as the Big Third Front, this inland heavy industrial base was to be built up with the help of enterprises re-located from the coast.[2]: 4 At a June 1964 Politburo meeting, Mao also advocated that each province should also establish its own military industrial complex as an additional measure (subsequently named the Small Third Front).[2]: 4

Other key leadership, including Deng Xiaoping, Liu Shaoqi, and Li Fuchun, did not fully support the notion of the Third Front.[2]: 7 Instead, they continued to emphasize the coastal development and consumer focus pursuant to the Third Five Year Plan.[2]: 7 The Gulf of Tonkin Incident on August 2, 1964, however, quickly changed the discussion about the Third Five-Year Plan.[2]: 7 Key leadership's fear of attack by the United States increased, and the Third Front received broad support thereafter.[2]: 7

In 1965, special commissions for Third Front Movement were established. On September 14, 1965, the Central Planning Commission submitted the final proposal for the Third Five-year Plan, where the Third Front Movement had the central position in the plan.

However, whether there would be war and whether the Third Front Movement was necessary had been under discussion even after the Third Five-Year Plan was passed. There was a famous episode of conversation when Mao was visiting Tianjin. Mao asked whether the Third Front Movement will be unnecessary and wasteful. The local cadre answered: ”No. Even the enemies will not come, the Third Front Movement will still be useful to economic development.” Mao was happy with the answer. In fact, investment in the Third Front region was largely affected by the security situation. The two climaxes of the Third Front region, was between 1965 and 1967 after the Gulf of Tonkin Incidence, and between 1970 and 1971 after the Conflict over the Zhenbao Island in 1969 with the Soviet Union.

Construction of the Third Front

The hallmark of the Third Front Movement was a strategic shift to China’s interior. On August 12, 1964, Zhou Enlai approved enormous industrial development in southwest China: Panzihua Iron and Steel (in Sichuan), Liupanshui coal mines (in Guizhou), and the building of railroads to connect Sichuan, Yunnan, and Guizhou.[2]: 9

In an August 19, 1965 report, Li Fuchun, Bo Yibo and Luo Ruiqing suggested that no new projects should be constructed in major cities in the First Front, that new projects should be built concealed in the mountains, and that industrial enterprises, research institutes, and universities should be moved to the Third Front.[2]: 9 Existing plants in the First and Second fronts, should be “split into two” (一分为二; yīfēn wéièr) and move one copy to the Third Front region.

The Third Front construction was primarily carried out in secret, with the location for Third Front projects following the principle of “close to the mountains, dispersed, and hidden” (靠山, 分散, 隐蔽; kàoshān, fēnsàn, yǐnbì).[1]: 179 This principle was motivated by national defense considerations; plants were required to be hidden in the mountains and were not allowed to be geographically clustered to minimize the damage of air strikes. Because construction of Third Front projects was based on these non-economic considerations, projects were extremely costly.[1]: 180 It was the most expensive industrialization campaign of the Mao-era.[2]: 2 Ultimately, construction of the Third Front cost the equivalent of US$2.5 billion, accounting for more than a third of China's spending over the 15 year period in which the Third Front construction occurred.[1]: 180

Third Front workers had varying reactions to being selected to work on the Third Front.[2]: 81–82 Rural recruits were inclined to view it as an advancement from work in the countryside to better compensated industrial work.[2]: 81 These material benefits helped ease the family separations that could occur as a result of Third Front work assignments. Urban recruits who already worked at state-owned enterprises in more developed coastal areas were more likely to be apprehensive because they already received the benefits of working at such enterprises.[2]: 81 If such urban recruits declined a Third Front assignment, they would lose their Party membership and right to work at state-owned enterprises.[2]: 81 Aside from material consequences, some urban and rural workers saw Third Front work favorably because it was to express their commitment to building Chinese socialism through bringing industry to undeveloped regions and building an industrial base to help protect China in the event of invasion.[2]: 82–83

Construction of the Third Front slowed during 1966.[2]: 12 As the Cultural Revolution ignited leftist extremism, Lin Biao, Chen Boda also replaced Li Fuchun, Peng Dehuai, and Deng Xiaoping as the actual leaders of the Third Front Movement. Peng and Deng were later purged by their political enemies. Lin Biao revised the principle to “Close to the mountains, dispersed, and hidden in the caves” (靠山, 分散, 近洞; kàoshān, fēnsàn, jìndòng), which required Third Front Projects to be located in the caves. Many plants were not able to produce qualified products due to difficult locations. An electronic plant in Guiyang was built in the caves. The humidity and dim light induced the products to be deficient. Plants were required to be dispersed geographically such that there would be alternative units producing in case some plants were destroyed. However, this principle was used to an extreme. About 90% of the 400 new Third Front projects in Shaanxi were located in places far away from cities. The airplane factory in Hanzhong, Shaanxi had 28 units of the plant were spread in 2 districts, 7 counties. One unit was spread in 7 villages. It was scoffed by some as “building airplanes by the side of henhouse”. Assembling parts required dozens of miles of transportation. While transportation infrastructure and communication was poor, production was often interrupted. Some plants were located in places prone to geographic hazards such as landslides and earthquakes. Location choices of the Third Front projects also did not consider accessibility to inputs and outputs. A shipyard on the Yangtze River near Chongqing was responsible to produce conventional powered submarines in the 70s. The up stream of the Yangtze River is too shallow for submarines. To test the submarines, they needed to be tugged to Shanghai some 2000 kilometers down the stream where the Yangtze meets the Pacific. No doubt the production is very inefficient.

There were countless defects in the Third Front projects. Part of the reason is that the Third Front movement was carried out in a hurry, many plants started producing while they were still being designed and constructed (边设计, 边施工, 边生产; biān shèjì, biān shīgōng, biān shēngchǎn). A second reason was that following the Sino-Soviet Split, thousands of Soviet experts left China. China had to use its own technologies, which were less developed by that time, in most of the Third Front projects. A third reason for the defects in the Third Front projects was because the difficult geographic locations. The Gezhouba Dam, China’s largest hydropower station by then, had to pause its construction for two years due to “errors in design”. Since the 1980s, deficiencies in design and construction in the Chengdu-Kunming Railway engulfed another 10 million yuan. The Jiuquan Steel factory, constructed in the early 1970s, still produced no steel but only small amounts of pig iron by 1980. These problems were widespread. Partly due to these problems, many Third Front plants went bankruptcy when the state-owned firms were made responsible for their own viability.

Besides newly built large projects, many Third Front plants were spinoffs or entirely moved from existing plants in other parts of the country. In a document issued in early 1965, plants in the First and Second Fronts were required to contribute their best equipment and workers to the Third Front Movement. This priority is reflected in the slogans at the time such as “Choose the best people and best horses for the Third Front," “For the people, get ready for war and get ready for famine” (备战备荒, 为人民; bèizhàn bèihuāng, wéi rénmín). Incomplete statistics show that between 1964 and 1970, 380 large projects, 145 thousand workers and 38 thousand units of equipment, were moved from the coastal areas to the Third Front region. Most of these firms came from cities like Shanghai, Beijing, Shenyang, Dalian, Tianjin, Nanjing. Approximately 400 state-owned enterprises were re-located from coastal cities to secret locations in China's interior regions.[2]: 3

In 1969, Third Front construction accelerated following the Chinese-Soviet border clash at Zhenbao Island.[2]: 12

Every Third Front project was a state-owned enterprise.[2]: 11

Ideological factors

To recruit and develop the labor force responsible for building Third Front projects, the CCP sought to develop a labor force committed to the Third Front campaign as a way to build socialist modernity.[2]: 11 The Party emphasized austere living and working, although not as an end in-and-of-itself, but as a means necessary for socialist development given the level of China's development at the time.[2]: 10

In mobilizing and recruiting workers for Third Front Projects, the Party instructed recruiters to "take Mao's strategic thought as the guiding principle, teach employees to consider the big picture, resolutely obey the needs of the country, take pride in supporting Third Front construction ... and help solve employees' concrete problems."[2]: 93 In the official perspective, it was a political privilege to be selected as a Third Front recruit.[2]: 80

Among the important recruitment mechanisms were oath-swearing ceremonies or mobilization meetings held at urban work units or rural communes.[2]: 94 At these events, local officials exhorted crowds to join the Third Front construction effort. The Party instructed them to urge workers to "learn from the PLA and the Daqing oilfield and use revolutionary spirit to overcome all difficulties."[2]: 94 The Party did not attempt to hide the challenges of working on the Third Front, however, and told local officials to "speak clearly about the difficulties, not boast, and not make empty promises."[2]: 94

Third Front factories often assigned workers to read the classic Mao speeches Remember Norman Bethune, The Foolish Old Man who Moved Mountains, and Serve the People.[2]: 94

Transition to the market economy

After Nixon’s China trip in 1972, investment to the Third Front region gradually declined. Rapprochement between the United States and China decreased the fear of invasion which motivated the Third Front construction.[1]: 180 After Reform and Opening Up began in 1978, China gradually wound down Third Front projects with a "shut down, cease, merge, transform, and move" strategy.[1]: 180

In the Seventh Five-Year Plan between 1986 and 1990, Third Front plants not making a profit were allowed to shut down. Some Third Front plants moved out of the mountains and caves to nearby small and medium sized cities where the geography and transportation were less difficult. Plants with workshops spread across many places gathered in one place. Third Front plants, especially military plants, were encouraged to produce for the civilian market (junzhuanmin).

As plants built during the Third Front construction were privatized over the period 1980 to 2000, many became owned by former managers and technicians.[1]: 181 As one example, Shaanxi Auto Gear General Works was privatized and became Shaanxi Fast Auto Drive Company; as of 2022 it is the largest automotive transmission manufacturer and its annual revenues exceed US$10 billion.[1]: 181

Evaluation and current role

Through its distribution of infrastructure, industry, and human capital around the country, the Third Front created favorable conditions for subsequent market development and private enterprise.[1]: 177 Once remote regions that were part of the Third Front continue to benefit from the influx of specialists during the Third Front construction and many enterprises, including many private ones, are legacies of the movement.[1]: 180 Because each plant built during the Third Front construction was relatively isolated, close knit communities with a high degree of social capital formed, which also helped facilitate the eventual privatization of Third Front plants.[1]: 181–182

A large part of the Third Front Movement was confidential. The mountainous terrain and geographical isolation of the region have added to this concealment. Due to the emphasis that China has placed on concealment of its special weapons capabilities, it is doubtful whether any other country, perhaps even including the United States, has identified all of China's special weapons related facilities. (Chinese Nuclear Weapons[3]) Many of them may still be hiding in the mountains.

Cities that benefitted from Third Front construction continue to have generally high degrees of development compared to the rest of their regions.[1]: 182 For example, Mianyang has become a high-tech city and Jingmen is regarded as one of China's most innovative cities.[1]: 182 However, the economic viability of a number of Third Front cities decreased after the end of the initiative, resulting in a "rust belt."[1]: 184–187 Panzhihua, for example, was a major steel producing Third Front city which has now experienced major population outflows.[1]: 184 Its local government now offers subsidies to those who move there and have second or third children.[1]: 184 Other "rust belt" cities turned their defunct plants into tourism destinations.[1]: 184 Hefei has successfully transitioned to high-tech industries, including those dealing with semiconductors, as well as alternative energy.[1]: 185

Despite the existence of "rust belt" cities, the Third Front Movement effectively narrowed regional disparities.[2]: 3 In 1963, 7 western provinces: Yunnan, Guizhou, Sichuan, Shaanxi, Ningxia, and Qinghai, accounted for 10.5% of China’s industrial output. This ratio went up to 13.26% by 1978. By 1980, the programs had created a railway grid linking previously isolated parts of western China,[4] in addition to a galaxy of power, aviation and electronic plants, said Zhang Yunchuan, minister of the Commission for Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense. (People's Daily Online[5]). Initial industries brought in by the Third Front plants and infrastructure kick-started the industrialization of China’s remote and mountainous west. Existing cities in the Third Front such as Xi’an, Lanzhou, Chengdu, Chongqing, and Guiyang benefited from large investments during this period. Cities such as Shiyan in Hubei, Mianyang and Panzhihua in Sichuan, were literally created by the Third Front Movement.

Another legacy of the Third Front was an increase in China's resolve in developing industrial systems with region-wide impacts.[2]: 28 China's Western Development, initiated in 2001, was shaped by the Third Front. Many cities developed during the Third Front are now involved in the Belt and Road Initiative.[1]: 187

Historiography of the Third Front

Starting in the 1980s, Chinese scholarship on the Third Front began being published.[2]: 18 Third Front studies have been published with greater regularity since 2000.[2]: 18 Generally, Chinese studies evaluate the Third Front positively, highlighting its role in the development of western China, while also acknowledging its economic difficulties and the harsh living conditions for those involved in Third Front construction.[2]: 18 Given the formerly secretive nature of the Third Front, Chinese researchers have benefitted from their unique access to archives, oral histories and interviews of participants, grey literature, and classified materials.[2]: 18 Outside of histories specifically focused on the Third Front, the general trend is that the Third Front is not thoroughly addressed, with Chinese histories of 1960s placing greater emphasis on the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution.[2]: 18

Like Chinese histories of the period, Western histories of 1960s China also tend to focus on the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution without significant discussion of the Third Front.[2]: 18 Compared to Chinese scholarship, Western research on the Third Front is relatively rare.[2]: 17 Notable exceptions include the work of Barry Naughton, who published the first Western scholarship on the Third Front in 1988 and 1991.[2]: 17

Media

- The Third Front is the setting for a recent Chinese film called Shanghai Dreams directed by Wang Xiaoshuai. Set in the 1980s, it is a bleak and thoughtful drama that shows the life of some ordinary families who had moved there and would like to move back to Shanghai.

- 11 Flowers, also directed by Wang Xiaoshuai, reflects the director's own experience growing up in a Third Front City.

- 24 City, directed by Jia Zhangke, follows three generations of characters related to a Third Front plant in Chengdu. The plant was moved from the Northeast and produces engines for airplanes. In the 2000s, its factory complex in downtown Chengdu was re-developed into a real estate project.

Further reading

- Chen, Donglin (2003). Sānxiàn jiànshè: Bèizhàn shíqī de xībù kāifā 三线建设:备战时期的西部开发 [The Third Front Movement: The Western Development in Preparation of War] (in Chinese). Beijing: Central Party School Press. ISBN 7-5035-2764-1.

- Meyskens, Covell (2015). "Third Front Railroads and Industrial Modernity in Late Maoist China". Twentieth-Century China. 40 (October): 238–260. doi:10.1179/1521538515Z.00000000068. S2CID 155767101.

- Naughton, Barry (1988). "The Third Front: Defence Industrialization in the Chinese Interior". China Quarterly. 115 (September): 351–386. doi:10.1017/S030574100002748X. JSTOR 654862. S2CID 155070416.

- China's military industry enterprises come out of mountains to world market

References

- Marquis, Christopher; Qiao, Kunyuan (2022). Mao and Markets: The Communist Roots of Chinese Enterprise. New Haven: Yale University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv3006z6k. ISBN 978-0-300-26883-6. JSTOR j.ctv3006z6k. OCLC 1348572572. S2CID 253067190.

- Meyskens, Covell F. (2020). Mao's Third Front: The Militarization of Cold War China. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108784788. ISBN 978-1-108-78478-8. OCLC 1145096137. S2CID 218936313.

- Chinese Nuclear Weapons - Federation of American Scientists website

- Meyskens, Covell (2015-10-01). "Third Front Railroads and Industrial Modernity in Late Maoist China". Twentieth-Century China. 40 (3): 238–260. doi:10.1179/1521538515Z.00000000068. ISSN 1521-5385. S2CID 155767101.

- China putting on a brave 'Third Front'