Armenians in Turkey

Armenians in Turkey (Armenian: Հայերը Թուրքիայում, romanized: Hayery T’urk’iayum) are ethnic Armenians living Turkey and one of the indigenous peoples of Turkey. Until the Armenian genocide of 1915, most of the Armenian population of Turkey lived in the eastern parts of the country that Armenians call Western Armenia.

Հայերը Թուրքիայում (Armenian) | |

|---|---|

Distribution of Armenian speakers in Turkey according mother tongue, census in 1965 | |

| Total population | |

| 50,000–70,000[1][2][3] Islamized and Crypto Armenians: est. 80,000–5,000,000[4][5][6][7] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Native: Armenian Other:

| |

| Religion | |

|

History

The presence of Armenians in Anatolia has been documented since the sixth century BCE, about 1,500 years before the arrival of Turkmens under the Seljuk dynasty.[9][10] The eastern part of Turkey was part of the kingdom of Armenia for centuries. Under reign of Tigranes the Great, for a long time headed the kingdom of Armenia, his domains stretched from the shores of the Caspian Sea to the Mediterranean, from Mesopotamia up to the Pontic Alps. The vast empire, formed of a varied mixture of diverse tribes, with their own dialects and cultures, could hardly be turned overnight into a cohesive and durable political structure. Inner disunity aided the designs of the Romans, who launched a series of onslaughts on the Armenian dynasty, beginning with the invasion by Lucullus in 69–68 B.C, and culminating in the campaigns of Pompey in Armenia, Iberia and Colchis in 66-65 B.C. The downfall of Tigranes the Great was precipitated by the flight of his son, Tigranes the Younger, to the court of the Parthian king Phraates III, who supplied him with an army with which to invade Armenia, and join forces with the victorious Romans.[11] The Kingdom of Armenia adopted Christianity as its national religion in the fourth century CE, establishing the Armenian Apostolic Church.[12] Following the end of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, two Islamic empires—the Ottoman Empire and the Iranian Safavid Empire—contested Western Armenia, which was permanently separated from Eastern Armenia (held by the Safavids) by the 1639 Treaty of Zuhab.[13]

From the mid-nineteenth century, Armenians faced large-scale land usurpation as a consequence of the sedentarization of Kurdish tribes and the arrival of Muslim refugees and immigrants (mainly Circassians) following the Russo-Circassian War.[14][15][16] In 1876, when Sultan Abdul Hamid II came to power, the state began to confiscate Armenian-owned land in the eastern provinces and give it to Muslim immigrants as part of a systematic policy to reduce the Armenian population of these areas. This policy lasted until World War I.[17][18] These conditions led to a substantial decline in the population of the Armenian highlands; 300,000 Armenians left the empire, and others moved to towns.[19][20] Some Armenians joined revolutionary political parties, of which the most influential was the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF), founded in 1890. These parties primarily sought reform within the empire and found only limited support from Ottoman Armenians.[21]

| Armenian revolutionary political parties in Ottoman parliament | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armenian Revolutionary Federation | Social Democrat Hunchakian Party | Armenakan Party | ||||

| Year | Total seats | +/– | Total seats | +/– | Total seats | +/– |

| 1908 | 4 / 275 |

1 / 275 |

1 / 275 |

|||

| 1912 | 10 / 288 |

0 / 288 |

0 / 288 |

|||

| 1914 | 4 / 275 |

0 / 275 |

0 / 275 |

|||

| 1919 | 0 / 160 |

0 / 160 |

0 / 160 |

|||

Abdul Hamid's despotism prompted the formation of an opposition movement, the Young Turks, which sought to overthrow him and restore the 1876 Constitution of the Ottoman Empire, which he had suspended in 1877.[22] Although skeptical of a growing, exclusionary Turkish nationalism in the Young Turk movement, the ARF decided to ally with the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) in December 1907.[23][24] In 1908, the CUP came to power in the Young Turk Revolution, which began with a string of CUP assassinations of leading officials in Macedonia.[25][26] In early 1909 an unsuccessful countercoup was launched by conservatives and some liberals who opposed the CUP's increasingly repressive governance.[27] When news of the countercoup reached Adana, armed Muslims attacked the Armenian quarter and Armenians returned fire. Ottoman soldiers did not protect Armenians and instead armed the rioters.[28] Between 20,000 and 25,000 people, mostly Armenians, were killed in Adana and nearby towns.[29] Unlike the 1890s massacres, the events were not organized by the central government but instigated by local officials, intellectuals, and Islamic clerics, including CUP supporters in Adana.[30]

On the eve of World War I in 1914, around two million Armenians lived in Anatolia out of a total population of 15–17.5 million.[31] According to the Armenian Patriarchate's estimates for 1913–1914, there were 2,925 Armenian towns and villages in the Ottoman Empire, of which 2,084 were in the Armenian highlands in the vilayets of Bitlis, Diyarbekir, Erzerum, Harput, and Van.[32] Armenians were a minority in most places where they lived, alongside Turkish and Kurdish Muslim and Greek Orthodox Christian neighbors.[31][32] According to the Patriarchate's figure, 215,131 Armenians lived in urban areas, especially Constantinople, Smyrna, and Eastern Thrace.[32] Although most Ottoman Armenians were peasant farmers, they were overrepresented in commerce. As middleman minorities, despite the wealth of some Armenians, their overall political power was low, making them especially vulnerable.[33] During World War I, the CUP—whose central goal was to preserve the Ottoman Empire—came to identify Armenian civilians as an existential threat.[34][35] CUP leaders held Armenians—including women and children—collectively guilty for "betraying" the empire, a belief that was crucial to deciding on genocide in early 1915. Minister of War Enver Pasha took war of Sarikamish after losing, Enver publicly blamed his defeat on Armenians who he claimed had actively sided with the Russians, a theory that became a consensus among CUP leaders.[36][37] Reports of local incidents such as weapons caches, severed telegraph lines, and occasional killings confirmed preexisting beliefs about Armenian treachery and fueled paranoia among CUP leaders that a coordinated Armenian conspiracy was plotting against the empire.[38][39] In February 1915, the CUP leaders decided to disarm Armenians serving in the army and transfer them to labor battalions.[40] Discounting contrary reports that most Armenians were loyal, the CUP leaders decided that the Armenians had to be eliminated to save the empire.[38]

The ethnic cleansing of Armenians during the final years of the Ottoman Empire is widely considered a genocide, there are different estimates for the number of Armenians who died from the genocide range from 800,000 to 1,500,000.[41]

In the Republic of Turkey, Christian Armenians are mostly lived in Istanbul. Through Armenians in Istanbul faced discrimination, they were allowed to maintain their cultural identity, unlike those elsewhere in Turkey. In addition, in many regions of Turkey, converted Crypto and Islamized Armenians live.

Geographical distribution

Istanbul

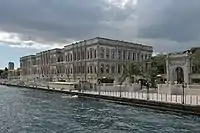

Of the 60,000 Christian Armenians living in Turkey, 45,000 live in Istanbul.[2] Today, in the Kumkapı quarter in Fatih, Istanbul, the various churches Armenian, Greek Orthodox and Syriac as well as the Armenian Patriarchate of Turkey. In some ways, the quarter has even regained its reputation as an Armenian quarter. Yet, the majority of Armenians residing in Kumkapı today are immigrants from Armenia, while of the original Armenian population, only a few individuals still call Kumkapı their home.[42] The Armenian population in Turkey, which makes up the largest Christian community in the country, "resembles an iceberg melting in the sea" with its some 60,000 members, the newly elected Armenian Orthodox Patriarch of Istanbul has said.[43] At present, the Armenian community in Istanbul has 20 schools (including the Getronagan Armenian High School), 17 cultural and social organizations, three newspapers (Agos, Jamanak, Marmara), two sports clubs (Şişlispor, Taksimspor).

Dersim

According to Mihran Prgiç Gültekin, the head of the Union of Dersim Armenians, around 75% of the population in villages of Dersim are "converted Armenians."[44][45] The greater part of hidden Armenians of Dersim, according Gultekin, is afraid that the nationalist regime may be back and may repress them. Currently over 200 families have announce their Armenian descent in Dersim, Gultekin said.[46] In April 2013, Aram Ateşyan, the acting Armenian Patriarch of Istanbul, stated maybe that 90% of Tunceli (Dersim)'s population is of Armenian origin.[47] In 2015, a group of citizens in Dersim (Tunceli) established the Dersim Armenians and Alevis Friendship Association (DERADOST). The opening ceremony of the association was attended by Hüseyin Tunç, then Deputy Mayor of Tunceli, Yusuf Cengiz, President of Tunceli Chamber of Commerce and Industry, representatives of non-governmental organisations and some citizens.[48][49] On the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, president of the association Serkan Sariataş said that the state should face its past history as soon as possible.[50] In 2015, 12 crypto-Armenians from Dersim baptized in Istanbul.[51] Through the 20th century, an many of Armenians living in the mountainous region of Dersim had converted to Alevism. During the Armenian genocide, many of the Armenians in the region were saved by their Kurdish neighbors.

Muş

| Armenian population in Muş Sanjak, 1914 | % Armenian | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Kaza | Total population[52] | Armenian population[53] | |

| Muş | 66,570 | 35,786 | 53.75% |

| Bulanık | 31,034 | 14,662 | 47.24% |

| Sasun | 13,959 | 6,505 | 46.60% |

| Malazgirt | 35,367 | 4,438 | 12.54% |

| Varto | 16,529 | 1,990 | 12.03% |

| Muş Sanjak | 163,459 | 60,682 | 37.12% |

In 2014, Armenians from Muş established an association. Daron Moush Armenians Solidarity Social Tourism Association made an official application after the formation of a board of seven members. The association, which started its activities in Muş and started accepting members, elected its president next week.[54] Speaking at the foundation ceremony of the Daron Muş Armenians Solidarity, Social and Tourism Association, board member Armen Galustyan said, "Regardless of religion, Armenianism is a race, a nation, just like the Turks, Kurds and Arabs. Armenianhood is not an enmity."[55][56]

Hatay

Vakıflı, located in the Samandağ district of Hatay province of Turkey, is the only Armenian village in Turkey with a population of 160 people, all of whom are Armenians. The entire village population is Armenian.[57]

Rize

The Hemshin people, also known as Hemshinli or Hamshenis or Homshetsi,[58][59][60] are an ethnic group who are affiliated with the Hemşin and Çamlıhemşin districts in the province of Rize, Turkey.[61][62][63][64] They are Armenian in origin, and were originally Christian and members of the Armenian Apostolic Church, but over the centuries evolved into a distinct ethnic group and converted to Sunni Islam after the conquest of the Ottomans of the region during the second half of the 15th century.[65]

Culture

Language

Most Armenians in Turkey speak Turkish, not Armenian, and this rate rises to 92 percent among young people.[66] On 21 February 2009, International Mother Language Day, a new edition of the Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger was released by UNESCO in which the [Western] Armenian language in Turkey was defined as a definitely endangered language, Also, Hamsheni, a branch of Western Armenian, was classified separately language.[67][68] Some Muslim Hamshenis, influenced by the fact that the Homshetsi dialect of Armenian is preserved as the spoken language in their circles, accept the fact that they are of Armenian origin. However, Hamshenis in Rize have mostly forgotten their mother tongue and they speak Turkish.[69]

The Armenian-speaking population in Turkey according to censuses

| Year | Total Armenian speakers[70] | % | Note | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1[70] | L2[70] | |||

| 1927 | 67,745 | 0.50% | 67,745 | – |

| 1935 | 67,381 | 0.42% | 57,599 | 9,782 |

| 1945 | 60,082 | 0.32% | 47,728 | 12,354 |

| 1950 | 62,098 | 0.30% | 52,776 | 9,322 |

| 1955 | 62,319 | 0.26% | 56,235 | 6,084 |

| 1960 | 72,200 | 0.26% | 52,756 | 19,444 |

| 1965 | 55,354 | 0.18% | 33,094 | 22,260 |

Music

Music culture especially developed among the Hamshenis. The first music album made by Homshetsi dialect is Vova, which consists of anonymous folk music.[71][72] The national Hamsheni instruments include tulum, şimşir kaval or the Hamshna-Zurna. Komitas, Rober Hatemo, Hayko Cepkin, Yaşar Kurt, Cem Karaca (half-Armenian), Udi Hrant Kenkulian can be given as an example to many Armenians working on Turkish and Armenian music.

Cinema and acting

In movie acting, special mention should be made of Vahi Öz who appeared in countless movies from the 1940s until the late 1960s, Sami Hazinses (real name Samuel Agop Uluçyan) who appeared in tens of Turkish movies from the 1950s until the 1990s and Nubar Terziyan who appeared in more than 400 movies. Movie actor and director Kenan Pars (real name Kirkor Cezveciyan) and theatre and film actress Irma Felekyan (aka Toto Karaca), who was mother of Cem Karaca.

Assimilation and Armenian place names

Although the Armenian place names in Turkey are mostly changed, some names are used officially today.

Linguist Sevan Nişanyan estimates that 3,600 Armenian geographical locations have been changed and changed Armenian place names make up 8.8% of place names in Turkey.[74]

Some province, district and place names of Armenian origin

Rize

- Ardeşen, from Armenian Ardaşén means "fieldvillage".

- Hemşin, from Armenian Hamamaşén/Hamşén means "Hamam's village". Çamlıhemşin is a combination of the Turkish word Çamlı and the Armenian word.

Diyarbakır

- Çermik, from Armenian Çermuk means "spa" .

Elâzığ

- Keban, from Armenian Gaban means "passage".

Ağrı

- Patnos, from Armenian Patnots maybe means "surrounded" or "fenced".

Muş

- Varto, it was recorded in 1554 as Varto kavar, which means "Vart's district" in Armenian. Varto is probably related to the Armenian personal name Vartan.

- Malazgirt, from Armenian Manavazagerd/Manazgerd means "Manavaz's fortress".

Şanlıurfa

- Siverek, from Armenian Seraverag means "black ruins".

Tunceli

- Pertek, from Armenian Pertag means "small castle".

- Mazgirt, from Armenian Medzgerd means "great fortress".

Malatya

- Arguvan, from Armenian Arkavan means "king's city/village".

Province names of Armenian origin

- Erzincan, from Armenian Erizagan means "Belonging to Erez", "from Erez".

- Bayburt, from Armenian Baberd, berd means "castle", but the structure of the compound is doubtful.

Demographics

Armenian population in Ottoman Empire according to censuses

| Year | Total population | % | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1881/82–1893[75] | 1,001,465 | 5.75% | 1,001,465 "Armenians" of 463,011 female and 538,454 male, not including Armenian Catholics. |

| 1906/7[76] | 1,120,748 | 5.36% | 1,031,708 "Armenians" of 547,526 male and 484,182 female, 89,040 "Armenian Catholics" of 47,991 male and 41,049 female. |

| 1914[77] | 1,229,007 | 6.63% | 1,161,169 "Armenians", 67,838 "Armenian Catholics". |

1914 census by vilayets

Armenians were found especially in the east of the Ottoman Empire, there were significant Armenian diasporas in Western Anatolia.

| Vilayet | Armenian population[77] | % |

|---|---|---|

| Bitlis | 117,492 | 26.85% |

| Van | 67,792 | 26.16% |

| Erzurum | 134,377 | 16.47% |

| Mamuret-ul-Aziz | 79,821 | 14.83% |

| Adana | 52,650 | 12.80% |

| Sivas | 147,099 | 12.57% |

| Diyarbekir | 65,850 | 10.62% |

| Hüdâvendigar | 60,199 | 9,76% |

| Constantinople | 82,880 | 9.10% |

| Angora | 51,576 | 5.40% |

| Trabzon | 38,899 | 3.46% |

| Adrianople | 19,773 | 3.13% |

| Konya | 12,971 | 1.64% |

| Aydın | 20,287 | 1.26% |

| Kastamonu | 8,959 | 1.16% |

| Other | 271,382 | |

| 1,229,007 | 6.63% |

1906/7 census by vilayets

| Vilayet | Armenian population[76] | % |

|---|---|---|

| Van | 64,108 | 39.63% |

| Bitlis | 95,393 | 32.04% |

| Erzurum | 116,180 | 17.19% |

| Mamuret-ul-Aziz | 67,522 | 14.26% |

| Diyarbekir | 52,013 | 13.24% |

| Sivas | 147,356 | 12,33% |

| Adana | 50,340 | 9.98% |

| Angora | 97,920 | 8.46% |

| Hüdâvendigar | 80,153 | 4.73% |

| Trabzon | 51,483 | 3.83% |

| Aydın | 19,045 | 1.10% |

| Other | 279,235 | |

| 1,120,748 | 5.36% |

References

- Lowen, Mark (2015). "Armenian tragedy still raw in Turkey 100 years on". BBC News. "From a pre-war Armenian population of two million, just 50,000 remain in Turkey today."

- "Foreign Ministry: 89,000 minorities live in Turkey". Today's Zaman. "The Foreign Ministry has prepared a report identifying the number of minorities living in Turkey and their houses of worship. According to the report, Turkey hosts 89,000 minorities, including 60,000 Armenians, 25,000 Jews and 3,000 to 4,000 Greeks. Containing detailed statistics about the minority groups in Turkey, the report reveals that 45,000 of approximately 60,000 Armenians reside in İstanbul."

- "Turkish-Armenian weekly Agos celebrates 20 years in print". Hürriyet Daily News. "Since its foundation 20 years ago, the newspaper has focused on Turkish politics as well as issues of interest to Turkey’s 70,000-strong Armenian community and other minorities such as Kurds, Greeks and Jews."

- Melkonyan (2008), p. 98.

- Danielyan, Diana (2011). ""Azg": Is the awakening of Islamized Armenians in Turkey possible?". Hayern Aysor. "Dagch says according to different calculations, there are 3–5 million Islamized Armenians in Turkey and that the Foundation’s most important mission is to awaken them."

- Khanlaryan, Karen (2005). "The Armenian ethnoreligious elements in the Western Armenia". Noravank Foundation. "Thus, we can come to the conclusions that in the geographical areal of our research the number of “Anatolian” “Official” Armenians is insignificant, less then 5.000, the number of “Islamized” Armenians excels the number of one million and reaches 1.300.000 and “Crypto” Armenians are more then 700.000."

- "500 bin Kripto Ermeni var". Odatv. (in Turkish) "Prof. Halaçoğlu, ülkemizde en az 500 bin “kripto Ermeni” olduğunu belirterek, bu gerçeği söylediğinde kendisini “kafatasçılıkla” suçlayıp, yargısız infaza tabi tutanların, bugün bunu açıklamasının sebebinin, Ermenilere emlak verme ve Türkiye’yi tazminat ödemeye zemin hazırlama olduğunu öne sürdü."

- "Turkey - Armenians". Minority Rights Group. "Of these, around 60,000 are Orthodox, 50,000 of whom live in Istanbul, around 2,000 are Catholic and a small number are Protestant."

- Ahmed (2006), p. 1576.

- Suny (2015), p. xiv.

- Lang (1983), p. 516.

- Payaslian (2007), p. 34–35.

- Payaslian (2007), p. 105–106.

- Astourian (2011), p. 56, 60.

- Suny (2015), p. 19, 21.

- Göçek (2015), p. 123.

- Suny (2015), p. 55.

- Astourian (2011), p. 62, 65.

- Suny (2015), p. 54–56.

- Kévorkian (2011), p. 271.

- Suny (2015), p. 87–88.

- Suny (2015), p. 92–93, 99, 139–140.

- Suny (2015), p. 152–153.

- Kieser (2018), p. 50.

- Kieser (2018), p. 53–54.

- Göçek (2015), p. 192.

- Suny (2015), p. 165–166.

- Suny (2015), p. 168–169.

- Suny (2015), p. 171.

- Suny (2015), p. 172.

- Suny (2015), p. xviii.

- Kévorkian (2011), p. 279.

- Bloxham (2005), p. 8–9.

- Suny (2015), p. 245.

- Akçam (2012), p. 337.

- Üngör (2015), p. 18–19.

- Suny (2015), p. 243.

- Suny (2015), p. 248.

- Kieser (2018), p. 235–238.

- Suny (2015), p. 244.

- Balakian (2009), p. 93.

- "Managing the difficult balance between tourism and authenticity: Kumkapı". Hürriyet Daily News. "Today, the various churches Armenian, Greek Orthodox and Syriac as well as the Armenian Patriarchate of Turkey, which are situated in Kumkapı, immediately remind the visitor of this multi-ethnic past. In some ways, the quarter has even regained its reputation as an Armenian quarter. Yet, the majority of Armenians residing in Kumkapı today are immigrants from Armenia, while of the original Armenian population, only a few individuals still call Kumkapı their home."

- "Armenian population of Turkey dwindling rapidly: Patriarch". Hürriyet Daily News. "The Armenian population in Turkey, which makes up the largest Christian community in the country, “resembles an iceberg melting in the sea” with its some 60,000 members, the newly elected Armenian Orthodox Patriarch of Istanbul has said."

- "Mihran Gultekin: Dersim Armenians Re-Discovering Their Ancestral Roots". Massis Post. "75 percent of Dersim population is converted Armenians, founder of “Union of Dersim Armenians” Mihran Gultekin told reporters in Yerevan (Dersim is a region of eastern Turkey, which includes Tunceli Province, Elazig Province, and Bingöl Province)."

- "Documentary on Islamized Armenians of Dersim Screened at Columbia University". Armenian Weekly. "Mihran Prgiç Gültekin, the head of the Union of Dersim Armenians, estimates that about 75% of the village’s population are “converted Armenians."

- "Mihran Gultekin: Dersim Armenians Re-Discovering Their Ancestral Roots". Massis Post. "The greater part of hidden Armenians of Dersim, according Gultekin, is afraid that the nationalist regime may be back and may repress them. Currently over 200 families have announce their Armenian descent in Dersim, Gultekin said."

- "Tunceli'nin yüzde 90'ı dönme Ermeni'dir". İnternet Haber. "Erkam Tufan, “Tunceli civarında çok fazla sayıda Kripto Ermeni olduğu söyleniyor bu doğru mudur?” şeklindeki sorusuna Ateşyan şu yanıtı verdi: [...] “Doğrudur Tunceli'nin yüzde 90'ı belki dönme Ermeni'dir. Neden derseniz 30 yaşlarında bir çocuk geldi bana ve ''benim köküm Ermeni'' dedi. ''Ben dönmek istiyorum'' dedi. Ben de ''ispatla dedim'' ispatlayamadı, kabul etmedim. Ama inatla gitti geldi, vazgeçmedi. Gitti, geldi rahatsız etti beni, daha sonra babası aradı. Beyefendi dedi ''ben belediye çalışıyorum emekli olayım bende İstanbul'a gelip döneceğim. Buradaki halkın yüzde 90'ı Ermeni'dir, lütfen kabul et'' dedi. Bende kabul ettim ders aldı, vaftiz oldu, kilisemizin üyesi oldu.”"

- "Tunceli'de Ermeni ve Alevi dostluk derneği kurdu". Hürriyet. "Tunceli'de bir grup vatandaş, Dersimli Ermeniler ve Aleviler Dostluk Derneği (DERADOST) kurdu. Moğultay Mahallesi Ata Sokak’taki bir iş hanında kurulan derneğin açılışına Tunceli Belediye Başkan Yardımcısı Hüseyin Tunç, Tunceli Ticaret ve Sanayi Odası Başkanı Yusuf Cengiz, sivil toplum kuruluşu temsilcileri ile bazı vatandaşlar katıldı."

- "Tunceli'de Ermeni ve Alevi Dostluk Derneği Kurdu". Haberler. "Tunceli'de bir grup vatandaş, Dersimli Ermeniler ve Aleviler Dostluk Derneği (DERADOST) kurdu. Moğultay Mahallesi Ata Sokak'taki bir iş hanında kurulan derneğin açılışına Tunceli Belediye Başkan Yardımcısı Hüseyin Tunç, Tunceli Ticaret ve Sanayi Odası Başkanı Yusuf Cengiz, sivil toplum kuruluşu temsilcileri ile bazı vatandaşlar katıldı."

- "DERADOST başkanından Erdoğan ile Davutoğlu'na Ermeni Soykırımı çağrısı". Ermeni Haber Ajansı. "Ermeni Soykırımı'nın 100. yılında Dersimli Ermeniler ve Aleviler Dostluk Derneği (DERADOST) Başkanı Serkan Sariataş, devletin bir an önce geçmiş tarihiyle yüzleşmesi gerektiğini söyledi."

- "12 crypto-Armenians from Dersim baptized in Istanbul". Hürriyet Daily News. "Twelve Armenians from Dersim, an older name of the eastern Turkish province of Tunceli, were baptized in an Armenian church in Istanbul on May 9, daily Agos has reported."

- Karpat (1985), p. 175, Ottoman Population, 1914 (continued).

- Karpat (1985), p. 174, Ottoman Population, 1914 (continued).

- "Muş Ermenileri derneklerine kavuştu". Agos. "Sasonlular, Sivaslılar, Malatyalılar ve Dersimlilerden sonra Muşlu Ermeniler de bir dernek kurdu. Daron Muş Ermenileri Dayanışma Sosyal Turizm Derneği, yedi kişilik yönetim kurulunun oluşmasının ardından resmi başvuruda bulundu. Muş’ta faaliyetlerine ve üye kabul etmeye başlayan dernek, önümüzdeki hafta başkanını seçecek."

- "Muş'ta Ermeni derneği açıldı". Hürriyet. "Muş’ta Daron Muş Ermeniler Dayanışma, Sosyal ve Turizm Derneği’nin kuruluş töreninde konuşan yönetim kurulu üyesi Armen Galustyan, “Dini ne olursa olsun Ermenilik de Türk gibi, Kürt gibi, Arap gibi bir ırktır, bir millettir. Ermenilik bir düşmanlık değildir” dedi."

- "Muş'ta Ermeni derneği açıldı". Haberler. "Muş’ta Daron Muş Ermeniler Dayanışma, Sosyal ve Turizm Derneği’nin kuruluş töreninde konuşan yönetim kurulu üyesi Armen Galustyan, “Dini ne olursa olsun Ermenilik de Türk gibi, Kürt gibi, Arap gibi bir ırktır, bir millettir. Ermenilik bir düşmanlık değildir” dedi."

- "Türkiye'deki tek Ermeni köyü: Vakıflı". Ermeni Haber Ajansı. "Türkiye'nin Hatay ilinin Samandağ ilçesinde bulunan ve 160 kişilik nüfusunun tamamı Ermenilerden oluşan Vakıflı, Türkiye'deki tek Ermeni köyü. [...] Köyü, diğer köylerden ayıran nokta ise köy ahalisinin tamamının Ermenilerden oluşması."

- Vaux (2001), p. 1.

- Simonian (2007).

- Dubin & Lucas (1989), p. 126.

- Vaux (2001), pp. 1–2, 4–5.

- Andrews (1989), pp. 476–477, 483–485, 491.

- Simonian (2007a), p. 80.

- Hachikian (2007), pp. 146–147.

- Simonian (2007), p. xx, Preface.

- "Turkologist Ruben Melkonyan publishes book “Review of Istanbul’s Armenian community history”". Panorama. "According to Melkonyan, Turkey’s Armenian community faces educational problem; the number of Armenian schools decreases year by year. This number has fallen from 47 to 16 with 3000 Armenian students. The expert said that only 18 percent of Armenian community speaks Armenian, the rest Armenians are Turkish-speaking. 92 percent young people is Turkish-speaking."

- "UNESCO: Türkiye'de 15 Dil Tehlikede". Bianet. "Kesinlikle tehlikede olanlar: Abazaca, Hemşince, Lazca, Pontus Yunancası, Çingene dilleri (Atlasta yalnızca Romani bulunuyor), Süryanice'ye benzeyen Suret (atlasa göre Türkiye'de konuşan kalmadı; konuşanların çoğu göçle başka ülkelere gitti) ve Ermenice."

- "Dünya nüfusunun yüzde 40'ı ana dilinde eğitimden yoksun: Türkiye'de 15 dil yok oluyor". Euronews. "Açıkça tehlikede: Abazaca, Hemşince, Lazca, Pontus Yunancası, Çingene dilleri, Süryaniceye benzeyen Suret, Batı Ermenicesi".

- "Kimdir Bu Hemşinliler?". Bianet. "Söz konusu ilçelerdeki Hemşinlilerin bir bölümü, çevrelerinde konuşma dili olarak Ermenice’nin Hamşen lehçesinin korunuyor olmasından etkilenerek, Ermeni kökenli oldukları gerçeğini kabulleniyor. Bu kabullenişin kaynağında, Hopa ve Borçka ilçelerinde Hemşinliler arasında Marksist ve ateist fikirlerin yaygın olması, Türk İslam etkisine karşı yerel kültürünü savunma işlevi de gördüğünü düşünüyorum. [...] Hopalı Hemşinliler’den farklı olarak, ana dilini unutarak Türkçeyi benimseyen Rizeli Hemşinliler için durum tamamen farklı. Çünkü burada Türkleşmenin izleri çok daha derin."

- Dündar (2000), p. 91.

- "Alt kimlik dertleri yok alt tarafı müzik yapıyorlar". Zaman Pazar. "Türkiyede ve dünyada ilk Hemşince albüm olma özelliği taşıyan Vova, Ada Müzikin başarılı bir çalışması."

- "Damardan Hemşin Ezgileri: VOVA". NTV Türkçe. "Dünyadaki, tamamı anonim Hemşin ezgilerinden oluşan ve Hemşince söylenmiş ilk müzik albümü olan ‘Vova’da, Hikmet Akçiçek tarafından Hopa Hemşinlileri’nden derlenen Hemşince ve Türkçe söylenmiş 10 türkü; biri Hemşin horonu olmak üzere Karadeniz kavalı ile çalınmış 3 ezgiden oluşan toplam 13 eser yer alıyor. Albüm, bir Ada Müzik yapımı."

- Nisanyan (2011), p. 55.

- Nişanyan (2011), p. 54.

- Karpat (1985), p. 148, Summary: Totals for Principal Administrative Districts.

- Karpat (1985), p. 168, Final Summary of Ottoman Population, 1906/7.

- Karpat (1985), p. 188, Summary of Ottoman Population, 1914.

Sources

- Dündar, Fuat (2000). Türkiye nüfus sayımlarında azınlıklar (in Turkish). Doz Yayınları. ISBN 9789758086771.

- Karpat, Kemal (1985). Ottoman population 1830–1914. The University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299091606.

- Simonian, Hovann H., ed. (2007). The Hemshin: History, Society and Identity in the Highlands of Northeast Turkey. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-79829-1.

- Hachikian, Hagop (2007). "Notes on the Historical Geography and Present Territorial Distribution of the Hemshinli". The Hemshin: History, Society and Identity in the Highlands of Northeast Turkey.

- Simonian, Hovann H. (2007a). "Hemshin from Islamicization to the End of the Nineteenth Century". The Hemshin: History, Society and Identity in the Highlands of Northeast Turkey.

- Vaux, Bert (2001). "Hemshinli: The Forgotten Black Sea Armenians". Harvard Working Papers in Linguistics. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Melkonyan, Ruben (2008). "The Problem of Islamized Armenians in Turkey" (PDF). Yerevan: Noravank Foundation: 98.

Finally, it would be interesting to quote several versions concerning the numbers of apostate Armenians. Different Turkish sources indicate those numbers as 80.000 to 600.000. Karen Khanlarian shows the figure of around 2 million, of which 700–750 thousands are Crypto Armenians, and those who are Islamized - 1.300.000 [8, p. 104].

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Dubin, Marc S. & Lucas, Enver (1989). Trekking in Turkey. South Yarra, Vic.: Lonely Planet. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-864420374.

- Ersoy, Erkan Gürsel (2007). Ethnic identity, beliefs and yayla festivals in Çamlıhemşin. in The Hemshin. p. 320.

- Balakian, Peter (2009). "Armenians in the Ottoman Empire". In Forsythe, David P. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Human Rights. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-19-533402-9.

Diplomats and journalists at the time estimated that between 800,000 and 1.2 million Armenians died in 1915 alone (Bryce and Toynbee, Treatment of Armenians in Ottaman Empire). In the summer of 1916 another 200,000 were massacred in the Syrian desert around Deir el-Zor. In addition, tens of thousands of women were abducted into harems or Muslim families, and as many children were taken into families and forced to convert to Islam. After the war, further massacres took place, in Marash in 1920 and Smyrna in 1922. In the end, from one-half to two-thirds of the more than 2 million Armenians living in their historic homeland in the Ottoman Empire were annihilated. In his autobiography, Totally Unofficial Man, Raphael Lemkin, the legal scholar who invented the concept of genocide as an international crime, put the figure at 1.2 million. The International Association of Genocide Scholars conservatively assesses that more than 1 million Armenians were killed, probably 1.2 to 1.3 million. Some historians put the figure at about 1.5 million.

- Nişanyan, Sevan (2011). "Hayali Coğrafyalar: Cumhuriyet Döneminde Türkiye'de Değiştirilen Yeradları". TESEV Demokratikleşme Programı (PDF) (in Turkish).

- Bloxham, Donald (2005). The Great Game of Genocide: Imperialism, Nationalism, and the Destruction of the Ottoman Armenians. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927356-0.

- Akçam, Taner (2012). The Young Turks' Crime against Humanity: The Armenian Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing in the Ottoman Empire. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15333-9.

- Üngör, Uğur Ümit (2015). "The Armenian Genocide in the Context of 20th-Century Paramilitarism". In Demirdjian, Alexis (ed.). The Armenian Genocide Legacy. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-1-137-56163-3.

- Kieser, Hans-Lukas (2018). Talaat Pasha: Father of Modern Turkey, Architect of Genocide. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-8963-1.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (2015). They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else: A History of the Armenian Genocide. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-6558-1.

- Kévorkian, Raymond (2011). The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85771-930-0.

- Lang, David M. (1983). "Iran, Armenia and Georgia". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3: The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanid Periods. Cambridge University Press. p. 516. ISBN 0-521-20092-X.

- Ahmed, Ali (2006). "Turkey". Encyclopedia of the Developing World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-57958-388-0.

- Astourian, Stephan (2011). "The Silence of the Land: Agrarian Relations, Ethnicity, and Power". A Question of Genocide: Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539374-3.

- Göçek, Fatma Müge (2015). Denial of Violence: Ottoman Past, Turkish Present and Collective Violence Against the Armenians, 1789–2009. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-933420-9.

- Payaslian, Simon (2007). The History of Armenia: From the Origins to the Present. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-7467-9.

.png.webp)