Hypergiant

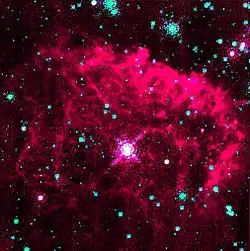

A hypergiant (luminosity class 0) is a star with an enormous mass and luminosity, It shows signs of a very high rate of mass loss. The exact definition is not yet settled.

Hypergiants are the largest stars in the universe, usually larger than supergiants.[1] The hypergiant with the largest known diameter is Stephenson 2-18,[2] which is about 2,150 times wider than the Sun.

Another large hypergiant is NML Cygni, about 1,650 times wider than the Sun. It is one of the extreme luminous supergiant stars.[3] A pulsating red hypergiant named UY Scuti is probably larger, with a radius of about 1,700 times the sun.

Hypergiants are very hard to find and they have a short lifespan because of their size. While the Sun has a lifespan of around 10 billion years, hypergiants will only exist for a few million years.

Spectrum

There are two special groups: luminous blue variables (LBV), and yellow hypergiants. Both of these types are very rare, with only a few examples in the Milky Way galaxy. Their rareness is probably because each type passes through this stage quite rapidly.

Stability

As luminosity of stars increases greatly with mass, the luminosity of hypergiants often lies very close to the Eddington limit. This is the luminosity at which the force of the star's gravity equals the radiation pressure outward.

This means that the radiative flux passing through the photosphere of a hypergiant may be nearly strong enough to lift away the photosphere. Above the Eddington limit, the star would generate so much radiation that parts of its outer layers would be thrown off in massive outbursts. This would effectively restrict the star from shining at higher luminosities for longer periods.

A good candidate for hosting a continuum-driven wind is Eta Carinae, one of the most massive stars ever observed. Its mass is about 130 solar masses and its luminosity four million times that of the Sun. Eta Carinae may occasionally exceed the Eddington limit.[4] The last time might have been outbursts observed in 1840–1860. These reached mass loss rates much higher than stellar winds would normally allow.[5]

Another theory to explain the massive outbursts of Eta Carinae is the idea of a deeply situated hydrodynamic explosion, blasting off parts of the star’s outer layers. The idea is that the star, even at luminosities below the Eddington limit, would have insufficient heat convection in the inner layers, resulting in a density inversion potentially leading to a massive explosion. The theory has, however, not been explored very much, and it is uncertain whether this really can happen.[6]

References

- However, note the definition is for huge luminosity and rapid mass loss, not simply size.

- July 2018, Nola Taylor Redd 26. "What Is the Biggest Star?". Space.com. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- Schuster M.T. (2007). Investigating the circumstellar environments of the cool hypergiants. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-549-32782-0. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- Owocki, S.P. & van Marle A.J. 2007 (2007). "Luminous Blue Variables & mass loss near the Eddington Limit". Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. 3: 71–83. arXiv:0801.2519. Bibcode:2008IAUS..250...71O. doi:10.1017/S1743921308020358. S2CID 15032961.

-

Owocki S.P; Gayley K.G. & Shaviv N.J. 2004 (2004). "A porosity-length formalism for photon-tiring limited mass loss from stars above the Eddington limit". The Astrophysical Journal. 616 (1): 525–541. arXiv:astro-ph/0409573. Bibcode:2004ApJ...616..525O. doi:10.1086/424910. S2CID 2331658.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Smith N. & Owocki S.P. 2006 (2006). "On the role of continuum driven eruptions in the evolution of very massive stars and population III stars". The Astrophysical Journal. 645 (1): L45–L48. arXiv:astro-ph/0606174. Bibcode:2006ApJ...645L..45S. doi:10.1086/506523. S2CID 15424181.