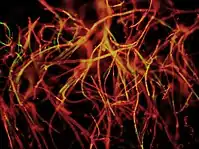

Mycelium

Mycelium (plural mycelia) is a root-like structure of a fungus consisting of a mass of branching, thread-like hyphae.[1] Fungal colonies composed of mycelium are found in and on soil and many other substrates. A typical single spore germinates into a monokaryotic mycelium,[1] which cannot reproduce sexually; when two compatible monokaryotic mycelia join and form a dikaryotic mycelium, that mycelium may form fruiting bodies such as mushrooms.[2] A mycelium may be minute, forming a colony that is too small to see, or may grow to span thousands of acres as in Armillaria.

Through the mycelium, a fungus absorbs nutrients from its environment. It does this in a two-stage process. First, the hyphae secrete enzymes onto or into the food source, which break down biological polymers into smaller units such as monomers. These monomers are then absorbed into the mycelium by facilitated diffusion and active transport.

Mycelia are vital in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems for their role in the decomposition of plant material. They contribute to the organic fraction of soil, and their growth releases carbon dioxide back into the atmosphere (see carbon cycle). Ectomycorrhizal extramatrical mycelium, as well as the mycelium of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, increase the efficiency of water and nutrient absorption of most plants and confers resistance to some plant pathogens. Mycelium is an important food source for many soil invertebrates. They are vital to agriculture and are important to almost all species of plants, many species co-evolving with the fungi. Mycelium is a primary factor in a plant's health, nutrient intake, and growth, with mycelium being a major factor to plant fitness.

Networks of mycelia can transport water [3] and spikes of electrical potential.[4]

"Mycelium", like "fungus", can be considered a mass noun, a word that can be either singular or plural. The term "mycelia", though, like "fungi", is often used as the preferred plural form.

Sclerotia are compact or hard masses of mycelium.

Uses

Agriculture

One of the primary roles of fungi in an ecosystem is to decompose organic compounds. Petroleum products and some pesticides (typical soil contaminants) are organic molecules (i.e., they are built on a carbon structure), and thereby show a potential carbon source for fungi. Hence, fungi have the potential to eradicate such pollutants from their environment unless the chemicals prove toxic to the fungus. This biological degradation is a process known as bioremediation.

Mycelial mats have been suggested as having potential as biological filters, removing chemicals and microorganisms from soil and water. The use of fungal mycelium to accomplish this has been termed mycofiltration.

Knowledge of the relationship between mycorrhizal fungi and plants suggests new ways to improve crop yields.[5]

When spread on logging roads, mycelium can act as a binder, holding disturbed new soil in place preventing washouts until woody plants can establish roots.

Fungi are essential for converting biomass into compost, as they decompose feedstock components such as lignin, which many other composting microorganisms cannot.[6] Turning a backyard compost pile will commonly expose visible networks of mycelia that have formed on the decaying organic material within. Compost is an essential soil amendment and fertilizer for organic farming and gardening. Composting can divert a substantial fraction of municipal solid waste from landfills.[7]

Commercial

Alternatives to polystyrene and plastic packaging can be produced by growing mycelium in agricultural waste.[8]

Mycelium has also been used as a material in furniture, and artificial leather.[9]

Construction material

In recent years, the concept of using mycelium as a construction material has been floated by artists and engineers. Mycelium has been successfully made in to strong and lightweight bricks, which are produced by pressing mycelium (obtained from agricultural waste) in to a mold and baking it in an oven. Artistic structures standing several meters high have been produced using mycelium bricks, which are described as a biodegradable and environmentally friendly alternative to concrete or clay bricks.[10][11][12]

See also

- Carbon sequestration – Storing carbon in a carbon pool (natural as well as enhanced or artificial processes)

- Thallus – Undifferentiated vegetative tissue of certain organisms

References

- Fricker, M.; Boddy, L.; Bebber, D. (2007). Biology of the fungal cell. Springer. pp. 309–330.

- "Mycelium". Microbiology from A to Z. Micropia. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Worrich, A.; et al. (2017). "Mycelium-mediated transfer of water and nutrients stimulates bacterial activity in dry and olgiotrophic environments". Nature. 8: 15472. Bibcode:2017NatCo...815472W. doi:10.1038/ncomms15472. PMC 5467244. PMID 28589950.

- Andrew Adamatzky (2022). "Language of fungi derived from their electrical spiking activity". Royal Society Open Science. 9 (4): 211926. arXiv:2112.09907. Bibcode:2022RSOS....911926A. doi:10.1098/rsos.211926. PMC 8984380. PMID 35425630.

- Wu, Shanwei (February 1, 2022). "Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi increase crop yields by improving biomass under rainfed condition: a meta-analysis". PeerJ. 10: e12861. doi:10.7717/peerj.12861. PMC 8815364. PMID 35178300.

- "Composting - Compost Microorganisms". Cornell University. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- Epstein, Eliot (2011). Industrial Composting: Environmental Engineering and Facilities Management. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1439845318.

- Kile, Meredith (September 13, 2013). "How to replace foam and plastic packaging with mushroom experiments". Al Jazeera America.

- Eleanor Lawrie (10 Sep 2019). "The bizarre fabrics that fashion is betting on". BBC.

- Sassine, Youssef Najib (6 October 2021). Mushrooms: Agaricus bisporus. CABI. p. 403. ISBN 978-1-80062-041-4.

- Dincer, Ibrahim; Colpan, Can Ozgur; Ezan, Mehmet Akif (14 November 2019). Environmentally-Benign Energy Solutions. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature. p. 743. ISBN 978-3-030-20637-6.

- Eggermont, Marjan; Shyam, Vikram; Hepp, Aloysius F. (21 February 2022). Biomimicry for Materials, Design and Habitats: Innovations and Applications. Elsevier. p. 501. ISBN 978-0-12-821054-3.

External links

- Mycelium at anbg.gov.au

.jpg.webp)

_mycelium_in_petri_dish_on_coffee_grounds.JPG.webp)

.JPG.webp)