/en/grammar/abbreviations-and-acronyms/content/

A comma is a punctuation mark that can be used in many different ways. Mainly, it's used to separate things—for instance, two thoughts in a sentence, multiple adjectives, or items in a list.

There are many rules that tell us how commas should be used, but don't let it scare you. With a little practice, it'll start to feel like second nature. Some rules are set in stone. They work the same way every time, so you don't have to think about them too much. Other rules are more complicated. In these cases, you have to understand the meaning of the sentence to know when and where to use the comma.

The basic rules for using commas are pretty foolproof. In other words, they're easy to apply to your writing because they always work the same way. You don't have to worry about any special exceptions or wonder where the comma is supposed to go. Each rule tells you exactly what to do.

You already know how to join two sentences using conjunctions like and, or, but, and so. We do it all the time in regular conversation, if not in writing.

As you can see, the comma goes between the two sentences, right before the conjunction. It tells you where one thought ends and another begins. Placing the comma after the conjunction would be incorrect because the conjunction is part of the second thought.

Commas can also be used to separate three or more items in a list. Just place a comma between each item (and an appropriate punctuation mark at the end). The last item is usually joined by a conjunction like and, or, or nor. Like the rule for joining sentences, the comma goes right before the conjunction.

![]()

There are certain types of place names (for example, city/state and state/country) that are always separated by a comma when you write them out. You can see this rule in action on any mailing envelope.

Phoenix is a place inside Arizona—that's why there's a comma between the city and state. This rule applies whenever you refer to a place in a similar way, whether it's MTV Studios, Times Square (which isn't even a city, state, or country) or England, United Kingdom.

Dates work almost the same way. For instance, when you write the full date, it should look something like this: January 1, 2014. It's almost as if the day and the month are inside the year—which is true, in a way. We're talking about January 1 in the year 2014. That's why there's a comma between the date and year.

Quotations are usually made up of two things: a quote (what the person said) and a tag (the person who said it). Commas play an important role too—they separate the quote from the tag, so we can tell they're separate but connected.

So where does the comma go? It depends on the layout of the sentence. Here are three examples.

To learn more, take a look at our lesson on Quotation Marks.

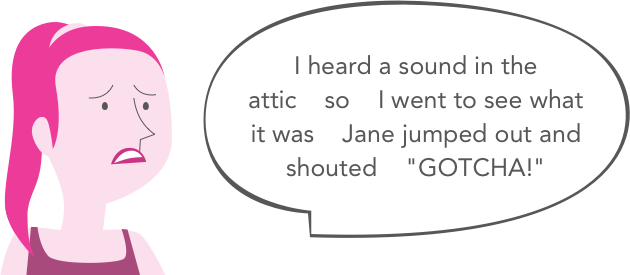

There are two commas missing from the example below. Can you tell where they're supposed go? Click the dots to see if you're right!

That's not quite right, but you're close. Remember: when joining two sentences, the comma always goes before the conjunction.

This is where the first comma should go—right before the conjunction. It tells you where one thought ends (I heard a sound in the attic) and another one begins (I went to see what it was).

This should be a period, not a comma. You can tell because the next sentence is a complete sentence (and there's no conjunction joining them together).

This is a good example of a quote that comes after a tag. In a case like this, the comma always goes before the quote (outside the quotation marks).

To use commas in more complicated sentences, you'll have to use your judgment. This means you'll need to think about each sentence (and make sure you really understand what makes it work) before you can apply the comma.

Don't let this scare you. As always, it's not the end of the world if you make a mistake. If you get stuck on a rule, try looking closely at the example—sometimes it helps to see the rule in action. If you're not a native English speaker, these rules can be especially difficult to grasp. You may want to ask someone you know for help, such as a friend, coworker, or teacher.

Another time you use commas is when you have two or more adjectives in a sentence. Just place the comma between them—this separates them and makes the sentence easier to read.

This rule is pretty universal, but it isn't always true. You should only use a comma if the adjectives are interchangeable.

Interchangeable means you can list the adjectives in any order and it won't change the meaning of the sentence. To find out if two adjectives are interchangeable, try reversing them—then see if the sentence still makes sense.

Here's the same example with a different pair of adjectives: delicious and frozen. This time, the adjectives aren't interchangeable. (If you reverse them, you can probably see why.) This means they shouldn't be separated with a comma.

![]()

The truth is, frozen yogurt is more than just an adjective followed by a noun. It's type of thing, like a miniature poodle, striped shirt, or even hot chocolate. All of these examples are made up of two words, but they represent a single thing. If you separate them with a comma—or write them in a different order—the words lose their meaning.

You might already know that an incomplete sentence is a fragment. When you begin a sentence with a fragment, it's called an introductory clause. (To learn more, check out our lesson on Fragments.)

It's perfectly OK to begin a sentence this way, then follow it with a complete thought. You just have to separate these thoughts with a comma. This makes the sentence easier to read, and it also tells the reader where to pause if needed.

In the example above, the thing before the comma (while you were sleeping) is a fragment; the thing after the comma (I gave you a new haircut) is a complete sentence. The comma is necessary only if the clause introduces the sentence. If the phrases were written in the opposite order, you wouldn't use a comma.

You should also use commas to separate nonessential clauses that appear in the middle of a sentence. A nonessential clause is something that adds meaning but that isn't completely necessary. In other words, if you took it out the sentence would still mean basically the same thing.

To find out if a clause is nonessential, try removing it from the sentence, then see how it sounds. The sentence above would still make sense if we removed the detail about the ascot. It would be: Steve is very tidy.

If the clause was essential, we wouldn't be able to remove it. Try this sentence instead: Men who wear ascots are very tidy. If we take out the detail about the ascot, we're left something slightly different: Men are very tidy. This is far too general to be true—after all, some men are really sloppy. This is how you know the clause is essential to the sentence's meaning.

As you gain more experience with commas, you'll run into cases when your judgment matters more than ever. These cases are more difficult to define, but they build on the rules we just discussed.

For instance, some sentences end with a type of fragment called a free modifier. This is just a fancy word for something that clarifies or relates to another part of the sentence. When you use a free modifier like this, always separate it with a comma.

![]()

Other sentences end with a distinct pause, followed by something more ambiguous. That final beat could be the name of the person you're talking to, a statement of confirmation, or a single word. Whatever it is, that beat also should be separated by a comma.

Below are two sentences that include a series of commas—one is correct, and the other is not. Use what you just learned to decide which one is correct, then click the dots to see if you're right!

Here, an essential clause has been mistaken for a nonessential clause. The sentence should be written without commas instead:

Those who live in glass houses shouldn't throw stones.

The comma in this sentence is used correctly. It separates the introductory clause (if you keep making that face) from the rest of the sentence (it's going to stay that way).

People often make the mistake of using a comma to join two sentences without a conjunction. For example:

![She was a small-town girl, he was a city boy. [WRONG] / She was a small-town girl, and he was a city boy. [RIGHT]](../../../../../media.gcflearnfree.org/ctassets/modules/49/small-town_girl.png)

Notice how the first version of the sentence is missing something? It needs a conjunction like and or but to join the two halves properly. You could also use a semi-colon to correct it instead: She was a small-town-girl; he was a city boy. Or you could rewrite the sentence as two sentences, with a period in between.

Remember how you're supposed to use a comma to separate three or more items in a list? Be careful not to go overboard and start separating two items that belong together (in other words, a compound subject or predicate).

![Aunt Ruth used to date the gym teacher, and the principal. [WRONG] / Aunt Ruth used to date the gym teacher and the principal. [RIGHT]](../../../../../media.gcflearnfree.org/ctassets/modules/49/aunt_ruth.png)

It might help to think of the compound as a single idea or thought. In the example above, the gym teacher and the principal are both part of Aunt Ruth's dating history—and they're the only things listed. You wouldn't break them up unless and the principal was rewritten as a complete sentence. For example: Aunt Ruth used to date the gym teacher, but she dumped him for the principal.

It's easy to confuse a fragment at the end of a sentence with an introductory clause—they do look similar. We already touched on this rule when we went over introductory clauses, but it can't hurt to review it once more.

![I went to Vegas, while my husband went camping. [WRONG] / I went to Vegas while my husband went camping. [RIGHT]](../../../../../media.gcflearnfree.org/ctassets/modules/49/vegas_camping.png)

A fragment only works as an introductory clause if it's at the beginning of a sentence. If it's at the end, you don't need a comma. In this example, the sentence would need a comma only if it was written in the reverse order: While my husband went camping, I went to Vegas.

Using a comma to force the reader to pause is a common mistake. Just remember: Commas are meant to make things easier to read, not necessarily influence the way they're read.

![And that, is how you deep-fry a turkey. [WRONG] / And that... is how you deep-fry a turkey. [RIGHT]](../../../../../media.gcflearnfree.org/ctassets/modules/49/deep-fry_turkey.png)

If you want the reader to pause, you'll have to get creative with your formatting. For instance, you could use an ellipses (a very common way of indicating a pause), like in the example above. Or you could write the word you want to emphasize in all caps or italics. This way, the reader can really feel the weight of it: And THAT is how you deep-fry a turkey.

/en/grammar/homophones/content/