This article was co-authored by Jake Adams. Jake Adams is an academic tutor and the owner of Simplifi EDU, a Santa Monica, California based online tutoring business offering learning resources and online tutors for academic subjects K-College, SAT & ACT prep, and college admissions applications. With over 14 years of professional tutoring experience, Jake is dedicated to providing his clients the very best online tutoring experience and access to a network of excellent undergraduate and graduate-level tutors from top colleges all over the nation. Jake holds a BS in International Business and Marketing from Pepperdine University.

This article has been viewed 31,003 times.

Writing a paper can be daunting, but it can be even more difficult to choose a topic. It can be hard to know where to start or if your area of interest will have enough resources to support a thesis. By brainstorming ideas, performing preliminary research, and refining your broad idea, you can select a thoughtful paper topic that you’ll feel excited and prepared to write about.

Steps

Brainstorming Paper Topics

-

1Determine if the paper needs to have a specific focus. If you aren’t allowed to select your own topic, you should carefully follow the instructions provided by your teacher or professor. You may be required to write a paper about a specific text, or a range of topics may be provided for you.

- If you are required to write about a specific text, think about the major themes in the novel or the conclusions drawn in a nonfiction book. This should help you narrow your focus.

- If you have a range of topics to choose from, consider which interests you most. You may also want to do some preliminary research on several topics to determine which has the most information available.

-

2Consult the syllabus. If you’ve been given free range to select your own paper topic, consult the syllabus to see what areas are most relevant to the course and the professor’s interests. Read over the objective of the course and review the assignments to date to get some ideas flowing.[1]

- Were there any projects or readings that particularly interested you? Use this as a guide to begin brainstorming potential ideas.

Advertisement -

3Do a timed writing exercise to create a list. Once you’ve refreshed your memories of recent work, gather a pencil and paper to create a list. Set a timer for 5 minutes and write down as many potential topics as you can think of in that time. Don’t be too critical of yourself at this early stage; you’re just trying to get some ideas out. You may find that your brain makes unexpected and pleasant connections.[2]

- These don’t need to be cohesive thesis statements. Just start creating a base of ideas.

- For a class on architecture, you might write down: Frank Lloyd Wright, mid-century modern, changes over time, Chicago, urban planning, influential architects, Mies van der Rohe, lots of windows, Prairie Style, nature.

-

4Look for patterns or areas of interest. Go through your list and use symbols, such as stars or asterisks, to note related ideas. Consider which ideas have lots of directions to choose from and which have fewer. Did you have a lot to say about one topic but struggled with others? Look for patterns to better understand where your interest lies.

- You’re more likely to write passionately about something that truly interests you.

-

5Narrow your list down to three potential topics. Using your brainstorm list as a guide, eliminate less interesting ideas until you have three potential topics or related keywords you might like to tackle. These don’t have to be firm thesis statements yet, they can just be narrower areas of focus you’d like to explore.

- For instance, using the architecture example above, three ideas might be: Mies van der Rohe and Chicago; nature and Prairie Style; and Frank Lloyd Wright and mid-century modern.

Performing Research to Select a Broad Topic

-

1Delve deeper using the encyclopedia. Use the Encyclopedia Americana, Encyclopedia Britannica, or another reputable encyclopedia to search for the key terms in the three broad topics you outlined.[3]

- Read the articles that come up, and keep a pad of paper nearby to write down any interesting facts or important information you discover. This will give you a more thorough understanding of the topics at hand.

-

2Read current newspaper articles about your potential topics. Search the databases of reputable newspapers, such as the Washington Post and the New York Times, for your topic keywords. This will bring up any current articles about your topics. This will also help you understand if there are any new or critical developments to consider as you choose an area to write about.[4]

- Some newspaper databases stretch back into the 1800s, so these can provide a historical perspective as well.

- Save the URLs of any particularly good or helpful articles, as they may be useful sources for you later on. This information can help you put together a Works Cited list as well.

-

3Ask a librarian for help. Make an appointment with a librarian at your school or public library. Bring any notes you’ve taken about your early research. Talk through your potential topics with the librarian and see what unique books or databases they think might be relevant to your research. This may introduce you to new angles on your potential topic.[5]

- For instance, in our architecture example, a librarian might be able to get you access to the digital archive of Architectural Digest or past articles by the Urban Land Institute.

- Write down any important passwords or usernames you need to access the resources your librarian makes available.

-

4Speak with an expert. Think about whether you know anyone who works in the field you are researching. If not, ask friends and family members if they know anyone, or do an online search for experts in that field. In many cases, you may be able to contact them by phone or email to ask them questions.

- An expert in the subject may have a deeper understanding of your topic ideas. They may be able to provide you with in-depth and specific expertise or advice.

-

5Be wary of using online sources. For academic papers, sites like wikipedia are generally not permitted. However, you could use a site like Google Scholar to help you find quality sources. Be sure to choose sources that are factual, rather than opinionated, and that adhere to any guidelines provided by your professor or teacher.

-

6Determine which topics have the most sources to draw from. After your preliminary research, take stock of which broad topics have lots of critical resources and which have fewer. Compare your notes in each of the 3 areas. You’ll want lots of good materials to support your thesis later.

-

7Choose a broad topic for your paper based on your research. The process of getting to know the topics better should have helped you better feel out which area is most of interest to you. Weigh your interest in what you’ve found out and the resources available. An area of high interest with a lot of resources is ideal.

- It’s a good idea to create a working thesis as you go to help get a feel for what kind of approach will make the most successful paper.

- In our architecture example, nature and Prairie Style architecture could be your broad topic to further refine.

Refining Your Broader Topic

-

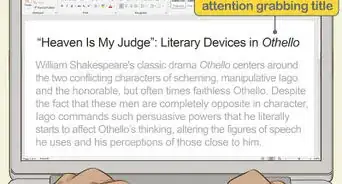

1Phrase your topic as a research question. Using your preliminary research as a guide, turn your broad idea into a research question that you will attempt to answer with your paper. It can be helpful to consider the relationship between your keywords.[6]

- Did one make or influence the other? Did they happen or live concurrently? The nature of your broad idea will inform the sort of question that makes sense.

- So, for example, rather than just nature and Prairie Style architecture, a research question could be: How did the Prairie Style architects represent nature in their architecture?

-

2Narrow the scope of your question by adding detail. Make your question more specific so you are addressing the topic in a unique way. The best way to do this is to restrict the topic by adding conditions.[7] Limitations about geography, time frame, or population are some popular ways of doing this.[8]

- So, How did the Prairie Style architects represent nature in their architecture on Chicago’s West Side? Or how did the Prairie Style architects represent nature in their architecture in the 1950s?

-

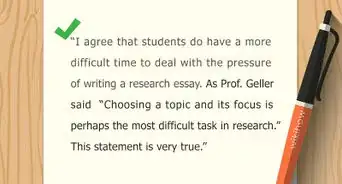

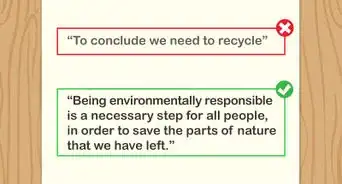

3Form a thesis statement. Now, use your preliminary research to form a basic answer to the question you created. This will be the topic of your paper and the idea around which you centralize deeper research going forward.[9] The answer might be obvious in your opinion based on what you’ve read, or you might want to revisit some articles and sources now that you’ve narrowed your topic.[10]

- Often there is no one right answer to a research query, and there doesn’t need to be! The answer depends on your opinion and how you interpret what you’ve read. Don’t be afraid to draw your own new conclusions.

- So, for example, how did Prairie Style architects represent nature in their architecture on Chicago’s West Side? The question might be answered, “The wide open green spaces of Chicago’s West Side inspired Prairie Style architects to add large windows. “This could be your paper topic going forward.

References

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/658/03/

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/658/03/

- ↑ https://www.umflint.edu/library/how-select-research-topic

- ↑ https://www.library.cornell.edu/research/introduction#1Choosinganddevelopingaresearchtopic-1Ch

- ↑ https://www.library.cornell.edu/research/introduction#1Choosinganddevelopingaresearchtopic-1Ch

- ↑ https://www.umflint.edu/library/how-select-research-topic

- ↑ https://www.sophia.org/tutorials/choosing-and-narrowing-a-topic-to-write-about-for

- ↑ https://www.umflint.edu/library/how-select-research-topic

- ↑ Jake Adams. Academic Tutor & Test Prep Specialist. Expert Interview. 20 May 2020.