This article was medically reviewed by Luba Lee, FNP-BC, MS. Luba Lee, FNP-BC is a Board-Certified Family Nurse Practitioner (FNP) and educator in Tennessee with over a decade of clinical experience. Luba has certifications in Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS), Emergency Medicine, Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS), Team Building, and Critical Care Nursing. She received her Master of Science in Nursing (MSN) from the University of Tennessee in 2006.

There are 8 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 9,884 times.

Serious illness can be a difficult thing to talk about. Perhaps you have been diagnosed with a serious illness and you would like to share this news with others. Or perhaps a friend or family member is sharing the news with you. Whatever the case, there are ways to remain sensitive, empathetic, and respectful to the needs of the person (or people) you’re talking to. Furthermore, if this type of discussion needs to happen with small children, there are some additional precautions you can take. As with any difficult subject, the most important thing is just to listen, be present, and show support.

Steps

Breaking the News to Loved Ones

-

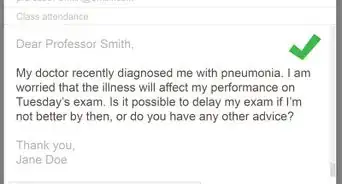

1Tell one close family member or friend. If you have been diagnosed with a serious illness, understand that it is not necessarily your responsibility to share this news with everyone you know. If you are ready to talk about it, one option is to discuss it with one close family member or friend, and then ask them to pass the news on to others. The benefit of this method is that it allows the news to spread somewhat passively, which may be easier for you.[1]

- You may begin by sitting that person down someplace private.

- You can start by saying, "I have something I need to tell you. I haven't shared this with anyone else. In fact, after I tell you, I'd like it if you could pass this information along."

-

2Hold a family meeting. Another option for sharing the news of your illness is to call a meeting with your family and close friends. This offers the benefit of telling many people at once, which may be easier on you. Furthermore, it allows your family and friends to support one another, and to offer a circle of support for you.[2]

- You can call your friends and family together in your home, or in the home of another family member.

- Sit everyone down in a circle.

- Start by saying, "There is something important I need to share with all of you."

- If you struggle with the words, you can be honest. Just explain, "This is difficult for me to talk about."

- If it helps you, you may want to prepare note cards or a script.

Advertisement -

3Tell people one at a time. Your third option is to tell your friends and family members individually, as you see them. This offers the most intimate conversations, which may offer you a deeper sense of support.[3]

- In this instance, you may not want the people you tell to share this information with others.

- If that is the case, be sure to explain, "I'd rather if you didn't share this with anyone. I'd like to opportunity to tell people myself."

-

4Ask a doctor or social worker to be present. No matter which route to sharing this news you select, it may be helpful to ask your doctor or social worker to be present. Your doctor and/or social worker may be able to answer questions about your health, your finances, and what you can expect moving forward. (Of course, how much of this information you choose you share is up to you). A doctor or social worker will also be skilled in navigating these types of discussions, and as such, can offer support.[4]

- Talk to your doctor or social worker ahead of time to determine what their role will be in this meeting.

- When you have these discussions, you can inform your loved ones of the role your doctor or social worker will play.

- For instance, you might say, "Dr. Williams is here to answer any questions you may have," or "Ms. Clancy is here as a kind of mediator, and to offer emotional support."

-

5Be prepared for a variety of reactions. Before you move into these conversations, try to understand that people will react to this news in all kinds of ways. As best as you can, try not to take these initial reactions personally. This news will likely come as quite a shock.[5]

- Some people may burst into tears.

- Others may laugh from nervousness.

- Some people will launch into “helpfulness mode.”

- Others may say nothing at all.

- If you give your friends and loved ones some time, you will likely see a wide range of emotional reactions from each of them, including sadness, anger, and fear.

-

6Ask for help. Many people will want to help you in some way, but they likely will not know how. Be honest about what you need and be forthright in asking for assistance.[6] You may need:

- Someone to pick up groceries for you

- Someone to drive you to an appointment.

- Help straightening up your home.

- Someone to talk to.

- You might say, "I need someone to pick up my groceries on Wednesdays. Do you think you could help me with that?"

Supporting a Loved One

-

1Listen. When a friend or loved one tells you that they have been diagnosed with a serious illness, your job in that moment is simply to listen. Do everything you can to stay present with them, make direct eye contact, and pay attention to what they are saying.[7]

- Maintain steady eye contact.

- Nod to show that you are listening.

- Ask questions, but don't pry.

- For instance, you might say, "May I ask what treatment plan you're going to follow?"

-

2Refrain from offering advice. Whenever we hear bad news from a friend, it is a natural reaction to try to solve the problem, or make them feel better. Unfortunately, this can make someone feel as though they are not being truly heard. Now is not the time to offer advice, remind them how it could be worse, or otherwise try to cheer them up.[8]

- Your reaction may be to say, "At least you have good insurance," or "At least you don't have what Judy had." Resist this urge. That is not what your loved one needs to hear.

- You may be tempted to try and cheer them up. Don't do this. Instead, allow them to feel what they are feeling.

- Offer empathetic responses that acknowledge the situation. Saying something as simple as "Wow, this sucks," is sometimes the very best thing to say.

-

3Admit that you don’t know what to say. If you feel dumbstruck, or tongue-tied, don’t allow your own discomfort get in the way of supporting your loved one. If you don’t know what to say (which is understandable), simply admit it and stay present to your loved one.[9]

- They don’t need to you say anything.

- They need you to listen.

- It is perfectly OK to say, "I really don't know what to say."

-

4Respect their privacy. When a friend or family member shares this kind of news with you, it is perfectly OK to ask questions. (As a matter of fact, asking questions shows that you are really listening.) However, which details they choose to share is completely up to them. Don’t pry, or insist they answer questions. At this sensitive time, it is crucial for you to respect their privacy.[10]

- Try beginning questions with the phrase, "May I ask . . ."

- If you ask a question and it gives your loved one pause, you may chime in to say, "If you're not comfortable sharing that, that's OK."

- You could also say, "If you'd prefer, we can talk about that later."

-

5Ask how you can help. An excellent way to offer support to your friend or loved one is to ask how you can help. Sometimes the ways we think we can help are not what is most needed. So ask first, and then help.[11]

- Simply ask, "What can I do to help?"

- It may help to offer up times when you are free. Such as, "Tuesdays and Thursdays are my open days, so if there is anything you need on those days, I'm you're person."

- Think about what resources you have to give. They may need rides to appointments, help at home, or most likely, just someone who can listen.

Talking to Children

-

1Let them know it’s OK to ask questions. When this sort of news is discussed with children, they may not how to engage. Let them know that it is OK for them to ask questions, and that these questions don’t need to come right away. Often a child will need hours, days, or even weeks to think before their questions surface, and that’s fine.[12]

- You can say, "It's OK for you to ask questions. And you don't need to ask them now. Anytime you think of a question, or just if you want to talk, come and find me."

-

2Be honest about your feelings. If a child says they are scared or sad, you can tell them you feel that way too. These discussions can bring about feelings that may be new to kids. When you share your own feelings, it helps them to know that their feelings are normal and natural, and that it is OK to feel that way.[13]

- You can say, "Are you scared about this? I'm scared too. This is a very scary thing to deal with, but those feelings will eventually pass."

-

3Inform caregivers. When you share this kind of news with kids, it is important to inform the other adults in the child’s circle. Talk to teachers, babysitters, or other caregiving family members. If all appropriate adults are kept in the loop, they can be available to help the child cope, and can better understand the child’s behavior.[14]

- Don't feel like you need to disclose anything you're not comfortable sharing.

- You can simply say to a teacher or caregiver, "We are experiencing a serious illness in the family. We've just told Tommy about it, and we're not really sure how he's going to react."

-

4Avoid comparing “death” and “sleep.” When a child encounters death for the first time, it is a common trend to describe death as “going to sleep.” Unfortunately, this has the unintended side effect of creating a fear of going to sleep for some kids. Avoid making this comparison when discussing death or serious illness with the kids in your life.[15]

- Rather than comparing death to sleep, simply try to describe it as honestly as you, within your family's belief structure.

- Children are capable of having complex discussions. Do your best to be honest with them.

References

- ↑ https://www.cancer.org/treatment/understanding-your-diagnosis/telling-others-about-your-cancer.html

- ↑ https://www.cancer.org/treatment/understanding-your-diagnosis/telling-others-about-your-cancer.html

- ↑ https://www.alz.org/help-support/i-have-alz/know-what-to-expect/sharing-your-diagnosis

- ↑ https://www.cancer.net/blog/2014-04/spotlight-oncology-social-workers-–-part-i-qa

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/06/magazine/how-to-tell-someone-youre-terminally-ill.html

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/06/magazine/how-to-tell-someone-youre-terminally-ill.html

- ↑ http://www.huffingtonpost.com/lisa-newlin/how-to-be-when-a-friend-i_b_5565236.html

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/06/magazine/how-to-tell-someone-youre-terminally-ill.html

- ↑ http://www.huffingtonpost.com/lisa-newlin/how-to-be-when-a-friend-i_b_5565236.html

- ↑ http://www.huffingtonpost.com/lisa-newlin/how-to-be-when-a-friend-i_b_5565236.html

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/06/magazine/how-to-tell-someone-youre-terminally-ill.html

- ↑ https://www.nhsinform.scot/care-support-and-rights/palliative-care/talking-to-people-about-your-condition/talking-to-children-about-your-condition#how-should-i-tell-my-children

- ↑ https://www.nhsinform.scot/care-support-and-rights/palliative-care/talking-to-people-about-your-condition/talking-to-children-about-your-condition#how-should-i-tell-my-children

- ↑ https://www.nhsinform.scot/care-support-and-rights/palliative-care/talking-to-people-about-your-condition/talking-to-children-about-your-condition#if-youre-not-going-to-recover

- ↑ https://whatsyourgrief.com/talking-to-children-about-death/

-Step-14-Version-2.webp)

-Step-14-Version-2.webp)

Medical Disclaimer

The content of this article is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, examination, diagnosis, or treatment. You should always contact your doctor or other qualified healthcare professional before starting, changing, or stopping any kind of health treatment.

Read More...