This article was co-authored by Richard Perkins. Richard Perkins is a Writing Coach, Academic English Coordinator, and the Founder of PLC Learning Center. With over 24 years of education experience, he gives teachers tools to teach writing to students and works with elementary to university level students to become proficient, confident writers. Richard is a fellow at the National Writing Project. As a teacher leader and consultant at California State University Long Beach's Global Education Project, Mr. Perkins creates and presents teacher workshops that integrate the U.N.'s 17 Sustainable Development Goals in the K-12 curriculum. He holds a BA in Communications and TV from The University of Southern California and an MEd from California State University Dominguez Hills.

There are 15 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 10,374 times.

Every really good piece of writing starts with a solid outline. Whether you’re teaching a class, tutoring fellow students, or homeschooling your kids, teaching the art of outlining requires a knowledge of the components of an effective outline, as well as an understanding of how they can be adjusted according to a writer’s specific style and purpose. Explain the function of each of these components to your students in detail, then guide them through a series of exercises designed to show them the hallmarks of a strong outline in action.

Steps

Explaining the Components of an Effective Outline

-

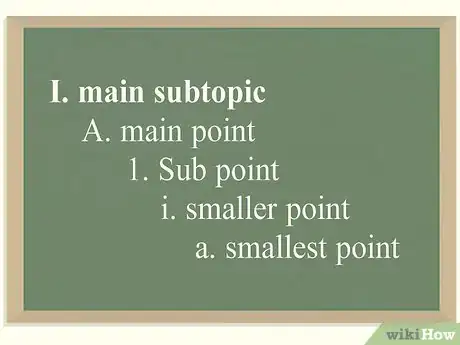

1Introduce your students to the standard alphanumeric outline format. Once your students have all chosen a subject for their essays, instruct them to assign a roman numeral to each major topic that they want to cover. Explain that these numerals will go on to become the topic sentences of their developed paragraphs, and that each one will correspond to a distinct section of the essay. To explore key ideas further, have them list individual supporting points beside capital letters on a series of indented lines below each roman numeral.[1]

- Inform your students that for complex topics, they can also include additional details or examples in regular numbered-list form beneath the relevant supporting point. Make sure they indent every next line to keep track of what information belongs where.[2]

- Teaching your students to use an alphanumeric outline format will provide them with a simple structure that they can fill in as they begin to expand their ideas.

-

2Stress the importance of the initial thesis statement. Give your students a heads-up that they should begin mulling over their thesis statement as soon as they decide on a topic. The thesis statement is the main idea of a piece of writing. It sums up what an essay, article, or scholarly paper is about and serves to introduce the reader to some of the ideas they’ll encounter later on.[3]

- Remember that there are different types of thesis statements. In an analytical essay, for instance, the thesis statement should express a particular fact about the subject, while in an argumentative essay, it should present a claim or seek to persuade.[4]

- Prompt your students with helpful preliminary questions to get them thinking about their thesis statement, like, “What do you want to say about this subject?” or, “Why do you think people should care about your topic?”

Advertisement -

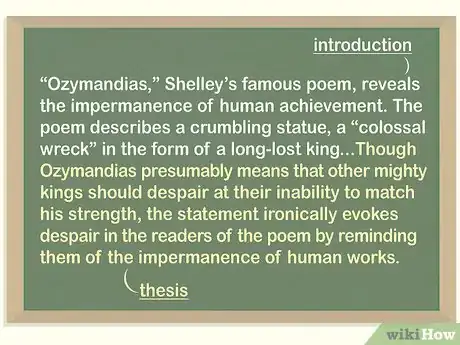

3Help your students draft an introduction based around their thesis statement. Once each of them has ironed out a concrete thesis statement, their objective will be to incorporate them into a larger piece of writing. Have them devise a rough opening paragraph that provides an overview of their topic of choice and builds to a summary of the point they want to make, or the main idea behind their thesis statement.[5]

- Encourage your students to ease into the writing process by starting with general information before working their way up to more specific ideas.[6]

- If the thesis statement of an essay is, “Pollution is bad for the environment,” the introduction might open with a definition of pollution and go on to describe some of the common forms it takes.

-

4Instruct your students to arrange their ideas into sections ranked by importance. With the introduction out of the way, it’s time to move onto the body of the essay. Explain that in order to keep the reader’s attention, it’s best to convey their biggest, most important ideas first. They can then use smaller details to add support to what they’re saying.[7]

- If a student's thesis statement is that it's unethical for businesses to lower wages in order to increase profits, for example, Section I of their outline might list the immediate consequences of cutting pay rates, while Section II might provide points detailing what happens when jobs are moved overseas.[8]

- Demonstrate to your students that by prioritizing their best ideas, everything that follows will seem like additional evidence for an already-established argument.

- Consider introducing the different elements of an outline (intro, body paragraphs, conclusion) in mini units so you can cover each part in-depth.[9]

-

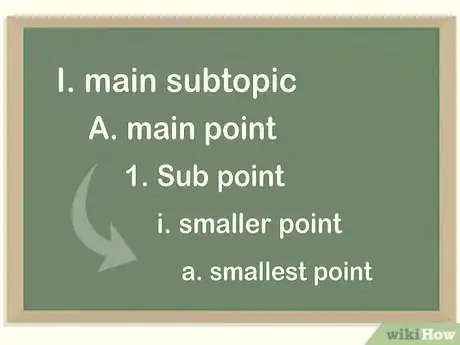

5Break up each section into digestible subtopics. If your students are uncertain about how to flesh out the numbered sections of their outlines, encourage them to use their indented letter lines to deep-dive into the same topic. This will get them in a frame of mind to treat each paragraph of their essay as its own miniature essay, complete with a thesis statement (roman numeral), supporting points (capital letters), and contextual info (Arabic numbers). This will ensure that every section adds something essential to the piece.

- Don’t forget to go over how to establish a logical flow. Following up a paragraph on the effects of sleep deprivation on standardized test scores with one providing a definition of sleep deprivation could feel disjointed and leave the reader confused. In this case, it makes more sense to define the term clearly before showing what it does.

Tip: In longer pieces, each important idea could encompass a series of paragraphs related by theme or evidence rather than a single self-contained paragraph.

-

6Offer your students guidance on crafting a memorable conclusion. Draw parallels between the introduction and conclusion and show how they work in tandem to book-end the body of the essay. Similar to the way the introduction delivers the thesis statement, a good conclusion should recap the main ideas found in each of the interior sections and create a sense of symmetry and finality, giving the piece the closure it needs.[10] [11]

- Advise your students not to rush their conclusions. They should understand that the conclusion is arguably the most critical part of the essay, as it gives them a chance to bring together each of the ideas they’ve been developing.[12]

- Direct your students to use clear and direct language to construct their closing paragraphs. Even if the findings of an essay are ambiguous, the statement made by the conclusion shouldn’t be.

Making Use of Helpful Exercises

-

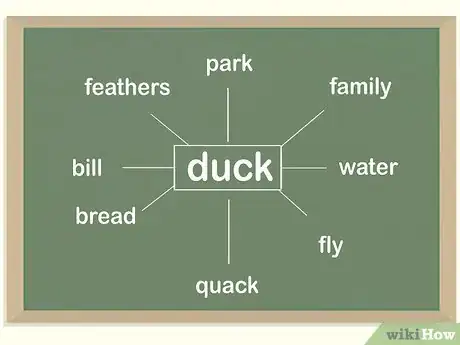

1Create word clusters to get your students generating ideas. Give your students a word and have them write it down inside a circle in the middle of a piece of paper. When they’re ready, set a timer for 5-10 minutes and challenge them to surround the word with smaller bubbles containing as many related words as possible. Reassure them that there are no wrong answers—all they’re doing is conditioning their minds to reflexively conjure up ideas they can then work into their essays.[13]

- If you give your students the word “duck,” for instance, they might end up with words like “water,” “feathers,” “bill,” “bread,” “park,” “quack,” “fly,” and “family.”

- Word clusters and other forms of free-association also make excellent warm up exercises before you actually get into organization or composition.

- This exercise will benefit students of all ages and writing levels, from grade school to college.

-

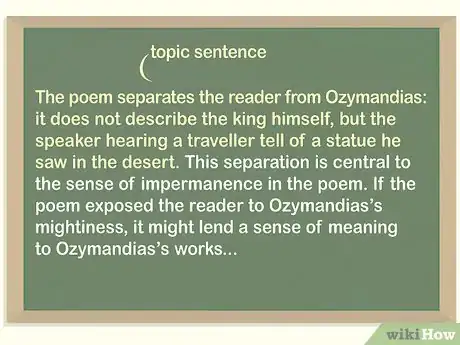

2Have your students identify the topic sentence in various sample paragraphs. Hand out a selection of scholarly papers, or photocopy a few passages from a textbook or nonfiction title to look at together. As you read through your example text, instruct your students to circle or underline what they think is the topic sentence in each paragraph. Afterwards, have them explain their reasoning for choosing the sentence that they did.

- Students who are below a high school reading level will have an easier time with texts containing short, direct sentences that convey simple ideas clearly.

- If you want to increase the difficulty of this exercise a bit, another option is to scramble the sentences in each paragraph so that they’re out of order and have your students pick the topic sentence out of the disorganized jumble.

Tip: History books make great teaching aids for dissecting paragraph structure, as they’re often meticulously organized and tend to proceed in a clear, linear manner.

-

3Practice creating outlines by deconstructing existing texts. For this exercise, your students will work in reverse to produce a detailed outline from a finished piece of writing. First, have them read through an example essay to familiarize themselves with the topic and content. Then, task them with dividing the information up into discrete sections, each with a main idea and a bulleted list of subtopics and supporting ideas stemming from the thesis or topic sentence.[14]

- You can either use the same text you used to pinpoint topic sentences or print off a different batch of examples to keep things fresh and get high school-aged students used to working with different kinds of information.

- One of the advantages of this exercise is that it allows students to focus exclusively on organizing key information without having to worry about what they’re writing.

-

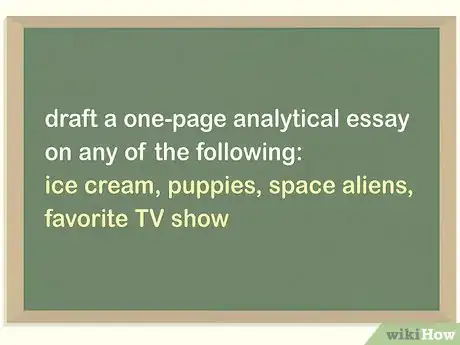

4Draft short mock essays on silly subjects. Have your students come up with an outline for a one-page analytical essay on ice cream, puppies, space aliens, their favorite TV series, or another simple and lighthearted topic. Then, give them 15-20 minutes to develop a rough essay from their outline. This will give them the opportunity to practice the skills they’ve been learning in a low-pressure environment.[15]

- Have your students spend at least 5 minutes planning what they're going to write.[16]

- Let young students write about their interests in order to keep them motivated.[17]

- The whole point of writing mock essays is to work quickly and freely, so be sure to tell your students not to stress over their word choice or rack their brains trying to make a compelling argument.

- Mock essays will be most useful to 5th and 6th grade students who are getting their first taste of essay-writing.

-

5Help older students come up with working titles for their essays. No piece of formal writing is complete without a title. Briefly touch on the title’s role in focusing the content of their essays and offering a preview of one or more of the key ideas or themes to come. Follow up with a brainstorming session to experiment with possible titles using elements pulled from their outlines.[18]

- Try this rapid-fire titling exercise with your students: think up a list of conditions (one word, two words, five words, begins with a question, references popular song lyrics, etc.) then give them 5 minutes to formulate a title that satisfies each of the conditions. By the end of the exercise, they’ll have a better grasp of how to formulate a title that serves a specific purpose.[19]

- Titling is one of the funnest parts of essay writing for many students. It lets them flex their creativity and show off their ability to appeal to the reader’s sensibilities on an emotional level.

References

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/the_writing_process/developing_an_outline/types_of_outlines.html

- ↑ https://www.tacoma.uw.edu/sites/default/files/global/documents/library/essay_outline_worksheet.pdf

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/thesis-statements/

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/the_writing_process/thesis_statement_tips.html

- ↑ https://www.umuc.edu/current-students/learning-resources/writing-center/writing-resources/getting-started-writing/prewriting-and-outlining.cfm

- ↑ https://www.bucks.edu/media/bcccmedialibrary/pdf/ThesisStatementsandIntroductionsJuly08_000.pdf

- ↑ https://www.brighthubeducation.com/help-with-writing/34236-how-to-write-an-outline/

- ↑ http://rasmussen.libanswers.com/faq/32339

- ↑ Richard Perkins. Writing Coach & Academic English Coordinator. Expert Interview. 1 September 2021.

- ↑ Richard Perkins. Writing Coach & Academic English Coordinator. Expert Interview. 1 September 2021.

- ↑ https://writingcenter.fas.harvard.edu/pages/ending-essay-conclusions

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/conclusions/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/faculty-resources/tips-on-teaching-writing/in-class-writing-exercises/

- ↑ https://busyteacher.org/20229-teaching-the-art-of-outlining-in-composition.html

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/faculty-resources/tips-on-teaching-writing/in-class-writing-exercises/

- ↑ Richard Perkins. Writing Coach & Academic English Coordinator. Expert Interview. 1 September 2021.

- ↑ Richard Perkins. Writing Coach & Academic English Coordinator. Expert Interview. 1 September 2021.

- ↑ https://umanitoba.ca/student/academiclearning/media/Writing_a_Great_Title_NEW.pdf

- ↑ http://writing.umn.edu/sws/assets/pdf/quicktips/titles.pdf