This article was co-authored by Bess Ruff, MA. Bess Ruff is a Geography PhD student at Florida State University. She received her MA in Environmental Science and Management from the University of California, Santa Barbara in 2016. She has conducted survey work for marine spatial planning projects in the Caribbean and provided research support as a graduate fellow for the Sustainable Fisheries Group.

There are 17 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 42,863 times.

Science fairs are important and fun parts of many people’s educational experience. While some people approach their science fair project as just something to get through, other people are more committed to creating a project that is potentially award winning. However, there are many challenges to creating a winning project. Not only do you need to pick an exciting topic, but you’ve got to commit yourself to carrying your experiment or study through and producing conclusions that are unique. But don’t worry, with a little bit of thought and a lot of work, you could just win that blue ribbon.

Steps

Gathering Information About the Project

-

1Schedule a meeting with your teacher or project coordinator. After you’ve learned about the science fair, schedule a time to briefly discuss it with your teacher or the project coordinator. This way, you’ll form a clearer understanding of the rules and parameters of the project.

-

2Get project rules and review them. Make sure you have your own copy of the science fair project rules and then review them in detail. This is extremely important, as you want to be sure about rules and other requirements of the project. Properly reviewing the rules will ensure that there are no surprises down the road.

- Get a highlighter and go through the rules, highlighting key rules and requirements.

- Review the schedule of the project, along with preliminary due dates and final due dates.

- Make sure to take a look at the next level of competition if you win your school or district’s competition.[1]

- If you are confused by anything in the rules or can’t find all the answers you’re looking for, check with your teacher or project coordinator.

Advertisement -

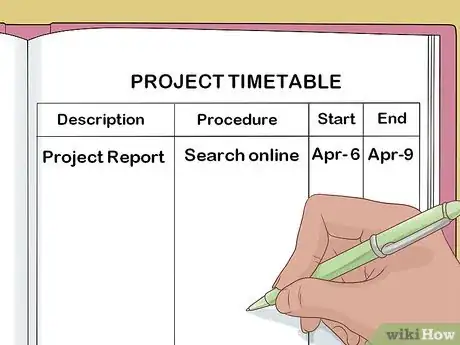

3Understand the timetable of the project. You might have several months to work on the project, or you might have just a few weeks. Once you’ve committed to competing in the project, look at the schedule and form an understanding of the important benchmarks you’ll have to meet to create a winning project. Keep your other responsibilities and obligations in mind (such as homework and extracurricular activities) when planning a schedule for your project.

-

4Choose a partner to work with on your science project, if you want and if allowed. If this is allowed, it can be a great way to cover more ground and share ideas together. One word of warning: choose wisely! Don't pair up with a person you know you won't work well with, or choose a particular partner just because they seem cool.

- Choose a person you have worked with in the past and have a good connection with.

- Avoid choosing a partner who isn't interested in science or who won't contribute equally.

- Work alone on your project if you do not work well with others, or if there are no suitable partners available.

Picking an Exciting Topic

-

1Think about what you find fun or interesting. Perhaps the most important element of winning a science fair is working on a project that you are excited and enthusiastic about. Being enthusiastic about your project will motivate you to go that extra mile. But if you’re not excited about the project, you probably won’t take the extra steps to do everything it takes to create the best project. To try to figure out what interests you, consider the following:

- Do you like to build things? Think about something mechanical.

- Are you interested in biology or agriculture? Consider a study of plant or animal life.

- Does the weather fascinate you? Consider a meteorology project.

- Brainstorm with your partner on this, if you have one.

-

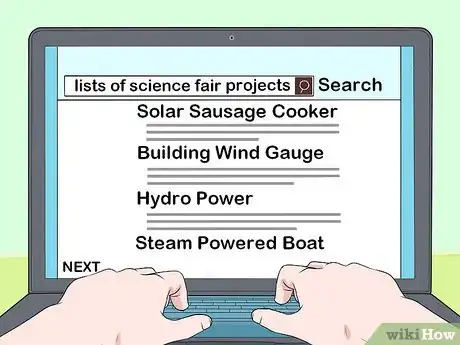

2Browse lists of potential science fair projects. There are many lists of really good potential projects available on the internet. Many of them have been done by other people, but they can serve as an inspiration for you to create your own unique project. Browse these lists to see if your interests line up with potential projects.[2] [3]

-

3Start doing research. If lists of projects don’t work out, start a search on your own. Using the subjects you find interesting, begin a search online, read books at your local library, or ask your teachers for certain topics that you may not know about, and might interest you.

- Begin with topics of interest to you personally and find scientific angles that arise from this interest.

- Ask yourself if the idea is doable before going too far with it.

- Don’t be afraid to spend time on research. You might have to spend a couple days or weeks at the library after school reading up on general topics in order to come up with an idea.[4]

-

4Try to develop an original project idea. Originality is often an important criterion for award winning projects. How original is your idea? The more original you are, and the more that you try to do an experiment in a different way from how it has been tried before, the better it will be received by the judges.[5]

-

5Vet your ideas. Once you’ve narrowed your potential projects down to a few, you need to examine whether they are good ideas, and whether they are doable or not. If you’ve got a brilliant idea, but you won’t have the resources or time to do it, then that idea is best shelved for another time. If you’ve got an easy idea, but it’s not original, don’t waste time on it.

- Discuss your favorite ideas with your science teacher to see if they think your potential projects might be good.

- Rank your ideas, and begin vetting the ones you are most interested in.

- Narrow your list down to the top 5.

- Make individual outlines for your top ideas. Make sure to briefly explore what your project will entail and how long it will take. Don’t spend more than a couple hours making your outlines for each idea. You might need to spend an hour or 2 on each idea. That’s okay.

- Put together preliminary budgets for each of your top 5. You might find that some projects are much more expensive than others, so keep this in mind when making your selection.[6]

Sorting Out the Logistics

-

1Decide on a location for the experiment. Your location may be limited by the project, or your experiment may be something you can do almost anywhere. Make sure to conduct the experiment or build your invention in the best, and most convenient, location possible. Consider these questions about your project:

- Can you do it in class?

- Can you perform your project at home?

- Will you be required to travel to conduct your experiment or to complete your project?

-

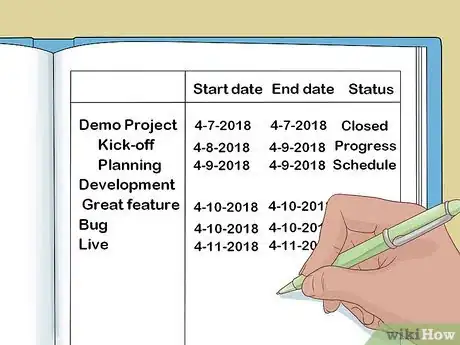

2Create a timeline for project completion. Now that you’ve got your project, and the basic information about it, you’ve got to create a timeline so you’ll be able to complete it before the due date. The timeline will really depend on how much time you have in your individual circumstances. Consider these factors:

- If your project is time-dependent, take that into account. For example, if you’re growing a cucumber plant, you’ll need to build in the 60-80 days that some varieties of cucumbers need to mature.

- If you’ve got to order supplies, build this in as well.

- Make sure to reserve time for compiling data, writing your reports, and designing your visual presentation after the experiment has concluded.[7]

-

3Put together a budget. Chances are, you don’t have an unlimited amount of money for your project. Find out how much you have, and then go through the list of resources you’ll need to acquire in order to create the project. This is something you might have considered earlier, but now you’ll have to make a much more specific budget. List every little thing you might need, as expenses mount quickly.[8]

-

4Work out what equipment and resources you need. Working out your equipment and resources should have been something you explored in the vetting process. Now you just need to secure that equipment and other resources, so that you have all of the items and needs sorted ahead of performing the experiment. If something is missing, the experiment might fail for lack of whatever it is rather than for other reasons.

- Is the equipment available in your school? Go ahead and secure permission to use it.

- Are you borrowing items from someone else? Talk to them and provide specifics on when you will need equipment or whatever else it is you are borrowing.

- Do you need to order special supplies online? Now is the time to go ahead and order those supplies.

-

5Consider what you need to keep safe during the experiment. This may be as simple as wearing old clothes or working over a sink. Or, it might mean that you need safety goggles, head protection or some sort of safe room or box, etc. Know what is needed before starting and be sure you can meet the all safety requirements completely.[9]

Completing Your Project

-

1Establish a hypothesis. For almost all science fair projects, you’ll need to start with a hypothesis. A hypothesis is an educated guess about how your project/experiment will work out. It is essentially your guess about what the results of the project will be. The results of your experiment will either support or contradict your hypothesis.

- The hypothesis needs to be something that you can and will test.

- You need to form a hypothesis before you begin the experiment or project.

- You should form your hypothesis after you’ve done a good job researching and sorting out your logistics.

- An example of a hypothesis is: “If I don’t water a fern for 10 days, the fern will die.”[10] [11]

-

2Perform the experiment you've chosen. Begin your project and start the experiment. Put time and care into whatever project you’ve chosen. This might be a long and tedious process, but it could just pay off with a blue ribbon!

- If you’re germinating seeds, make sure you do it correctly.

- If you’re building some sort of device or contraption, make sure you don’t do it in a rush.

- If you’re doing something that requires it, include a control element to test the outcomes against.

-

3Document everything. Along the way, document every part of the process and experiment. All of this documentation will help you when it comes time to compile your data and create your reports. It is best to over-document instead of under-document, as you never know what information might be useful when you’re creating your report and arriving at conclusions.

- Take photos if possible.

- Keep dated and timed records.

- Keep a journal of everything you do, everything you observe, and what works and doesn’t work. If you’re testing a new model airplane and something small failed, document that in your journal.

- Consider a video diary of your experiment. This way is a great way to capture small details without spending lots of time writing them down.[12]

-

4Resolve your hypothesis. Once you’ve completed your experiment, you need to look at the data and decide whether or not your hypothesis was correct. Don’t be afraid to be wrong. Let the data speak for themselves. After all, you’re the one that performed the experiment, and if you did so diligently, then that is really good evidence either for or against your hypothesis.

-

5Form your conclusions. After you’ve resolved your hypothesis and reviewed the data, you need to come to a larger conclusion about the project. What do your data really say about what you were testing or creating? Be brave when it comes to this. If you’ve got results that contradict what others have previously said, don’t hide it. After all, you’ve documented your process and you have evidence to support your results.

- When forming your conclusion, do so in a clear and concise way. Make sure you can easily articulate your conclusion.

- Don't guess or jump to conclusions that are not supported by facts, data, and observation.

- Don't let your hypothesis or expectations cloud your conclusion. Let the results speak for themselves.[13]

Creating Your Report

-

1Prepare graphs, images and videos. Using the data you’ve documented and collected, prepare graphs, tables, or other ways of displaying your information. Print out or develop your photographs. Edit your videos. These elements highlight your data and process. They make it easier for people to read your paper/poster/outline, etc. and makes the end result more interesting.[14]

- If you choose to make a video, make sure that it is easy to hear, logical in sequence, and shows clearly what has been done. Back up a video with a printed overview, as a paper copy of the things said in the video will help the judges and can be read by anyone interested.

- Make sure graphs are labeled clearly and are large enough to be viewed from at least 5 feet (1.5 meters) away.

- Make sure you include short explanations (at least 1-2 sentences) of any data you include through graphs or images.

- If you’ve got some sort of invention, make sure you clean it (of grease, oils, saw dusts, whatever) and prepare it to be displayed to others.

-

2Create a written report. Using all of your data, create a written report of your project. The length of the written report might vary, depending on specific contest rules. It may range from 3 to 20 pages. It may also depend on your project, the importance and number of images and graphs you include, and more. Consider including:

- A brief overview of the project that explains your project in clear and concise terms, and explains why you were interested in it in the first place.

- Your preliminary research.

- Your hypothesis.

- The process of your experiment.

- Your findings.

- Your conclusions. Also make sure to make a comment about the relevance or practical usage of your findings in everyday life.[15]

-

3Prepare a display of your experiment. Perhaps the most important part of your project, after the experiment itself, is preparing a visual display of your project. This display will often include graphs and images that you’ve already created. It will often be on a large cardboard or poster board display. You’ll include much of the same information you included in your written report, but it will be condensed considerably so people can view the project quickly and get a good idea of your process and findings. Consider including:

- The hypothesis you tested.

- An explanation of how the experiment was carried out.

- An outline of your findings.

- General and specific observations of what happened during the experiment

- Graphs, charts, and images that are particularly helpful for individuals seeing your project for the first time.

- Anything unusual or interesting that you spotted.

- The conclusions you've reached, detailed and explained clearly.[16]

-

4Practice an oral presentation. Your oral presentation is going to be extremely important when it comes to communicating your findings to judges and others who will be viewing your project. Make sure your oral presentation highlights and explains all of the material on your visual presentation.

- Talk judges and other observers through the material on your poster board.

- Make sure your oral presentation is between 3 and 5 minutes long.

- Practice this presentation to family and friends ahead of delivering it in front of a class or in front of judges.

- Speak clearly and slowly when delivering your oral presentation.

-

5Be prepared to answer questions. Make an answer sheet with FAQs (frequently asked questions) that you think students, teachers and judges might ask. This will help you to identify important things to focus on in your presentation and it will help calm any nerves you might have about being asked questions.[17]

-

6Enjoy presenting the project. You've put in a lot of effort and helped continue humanity's quest for knowledge about the world and universe in which we live. Through sharing your ideas with others, you're helping to keep the scientific tradition going. Be enthusiastic and to think about your project as something important.

Community Q&A

-

QuestionHow can I not be shy when I'm presenting in front of the whole school?

Community AnswerPractice in front of someone who will be there, then when you're presenting, find them in the audience and focus on them.

Community AnswerPractice in front of someone who will be there, then when you're presenting, find them in the audience and focus on them. -

QuestionHow can I make my project stand out from my competition?

Luna RoseTop AnswererStart your project earl so you have lots of time. Research it carefully. Spell-check everything. Use color to decorate it, and choose a color scheme (e.g. red, purple, and blue) to make it stand out. Don't be afraid to ask an adult to help proofread or brainstorm with you. Time and effort do make a big difference. Do your best, and be proud of your results.

Luna RoseTop AnswererStart your project earl so you have lots of time. Research it carefully. Spell-check everything. Use color to decorate it, and choose a color scheme (e.g. red, purple, and blue) to make it stand out. Don't be afraid to ask an adult to help proofread or brainstorm with you. Time and effort do make a big difference. Do your best, and be proud of your results. -

QuestionShould I hand write or type my information on the poster board?

Oliviap3016Community AnswerWhichever you think fits your project best. If you have neat handwriting and think it would look good on the poster, feel free to write it! If your handwriting is usually messy, typing may be better for you.

Oliviap3016Community AnswerWhichever you think fits your project best. If you have neat handwriting and think it would look good on the poster, feel free to write it! If your handwriting is usually messy, typing may be better for you.

Warnings

- Don't plagiarize other people’s work. Copying doesn't advance human knowledge, and you can lose marks or worse if the judges find out.⧼thumbs_response⧽

- Choose your topic wisely. A topic that is too hard or too odd will make the whole project less enjoyable.⧼thumbs_response⧽

References

- ↑ https://student.societyforscience.org/international-rules-pre-college-science-research

- ↑ http://www.sciencebuddies.org/science-fair-projects/science_project_ideas.php

- ↑ http://sciencefair.math.iit.edu/projects/

- ↑ http://school.discoveryeducation.com/sciencefaircentral/Science-Fair-Projects.html

- ↑ http://reekoscience.com/science-resources/science-fair-secrets-how-to-win-the-science-fair

- ↑ http://www.cyberbee.com/science/prep_sites.html

- ↑ http://school.discoveryeducation.com/sciencefaircentral/Getting-Started/Sample-Timeline.html

- ↑ http://www.moneycrashers.com/elementary-science-fair-project-ideas/

- ↑ http://www.sciencebuddies.org/science-fair-projects/project_ideas/Safety_Guidelines.shtml

- ↑ http://www.sciencebuddies.org/science-fair-projects/project_hypothesis.shtml#keyinfo

- ↑ http://www.softschools.com/examples/science/hypothesis_examples/104/

- ↑ http://ecuip.lib.uchicago.edu/sciencefair/html/wizard/02_experimenting_06b_Documenting-data.html

- ↑ http://www.sciencebuddies.org/science-fair-projects/project_conclusions.shtml

- ↑ www.exposciencesnb.ca/bar-graphs-tables-pie-charts-oh-my.pdf

- ↑ http://www.sciencebuddies.org/science-fair-projects/project_research_paper.shtml

- ↑ http://www.super-science-fair-projects.com/science-fair.html

- ↑ http://debmcalister.com/2013/02/03/how-to-help-your-kid-win-a-science-fair/

-Electric-Shock-Step-9.webp)