Centralist Republic of Mexico

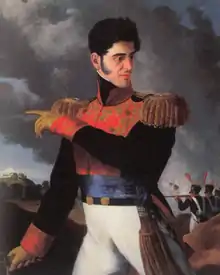

The Centralist Republic of Mexico (Spanish: República Centralista de México), or in the anglophone scholarship, the Central Republic,[2] officially the Mexican Republic (Spanish: República Mexicana), was a unitary political regime established in Mexico on October 23, 1835, under a new constitution known as the Seven Laws after conservatives repealed the federalist Constitution of 1824 and ended the First Mexican Republic. It would ultimately last until 1846 when the Constitution of 1824 was restored at the beginning of the Mexican American War. Two presidents would predominate throughout this era: Santa Anna, and Anastasio Bustamante.

Mexican Republic República Mexicana | |

|---|---|

| 1835–1846 | |

| |

| Capital | Mexico City |

| Common languages | Spanish (official), Nahuatl, Yucatec Maya, Mixtecan languages, Zapotec languages |

| Religion | Roman Catholic (official religion) |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic under a military dictatorship |

| President | |

• 1835–1836 | Miguel Barragán (first) |

• 1846 | José Mariano Salas (last) |

| Legislature | Congress |

| Senate | |

| Chamber of Deputies | |

| History | |

| 23 October 1835 | |

| 15 December 1835 | |

| 2 March 1836 | |

| 28 December 1836 | |

| 1846–1848 | |

| 22 August 1846 | |

| Population | |

• 1836[1] | 7,843,132 |

• 1842[1] | 7,016,300 |

| Currency | Mexican real |

| ISO 3166 code | MX |

| Today part of | Mexico United States |

| History of Mexico |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The Centralist Republic marked nearly ten years of uninterrupted rule by the Conservative Party. Conservatives had attributed the political chaos of the First Mexican Republic to the empowerment of states over the federal government and mass participation in the political system through universal male suffrage. Conservative elites saw the solution to the problem as abolishing the federal system and creating a centralized one, reminiscent of the political system during the colonial era.[3]

The political and economic chaos that had marked the First Republic, however, continued well throughout the Centralist Republic. Infighting among the conservatives resulted in administrations continuing to be interrupted by successful military coups, and another centralist constitution known as the Bases Orgánicas would be attempted in 1843. Significant political and military agitation for the restoration of the federalist system continued as well. The period was marked by multiple secession attempts across Mexico, including the loss of Texas and Yucatan, and two international conflicts: the Pastry War, caused by French citizens' economic claims against the Mexican government, and the Mexican–American War, as a consequence of the annexation of Texas by the United States.

Background

The First Mexican Empire fell in 1823, without having produced a constitution for the newly independent nation. Such a responsibility now fell upon the Supreme Executive Power, which was serving as a provisional government. The controversy between centralism and federalism first notably emerged during the debates regarding the new constitution, through factions which would eventually become the liberals and the conservatives. The most prominent opponent of the federal system during these debates was Father Mier. He argued that the nation needed a strong centralized government to guard against Spanish attempts to reconquer her former colony, and that a federation rather suited a situation in which previously sovereign states were attempting to unite as had happened with the United States. New Spain had never been made up of autonomous provinces; federation for Mexico, according to Mier would then be an act of separation rather than unification and only lead to internal conflict.[4] The arguments for federation prevailed however, motivated by the long struggle during the independence war to seek as much autonomy as possible, and an eagerness to reap the salaries that would accompany local bureaucracies.[5]

The newly established First Mexican Republic proved to be unstable, and presidential administrations were regularly interrupted by military coups. By 1833, the progressive Valentín Gómez Farías was president of the republic, sharing power with Antonio López de Santa Anna, who at this point supported the liberals. The Farías administration however provoked opposition most notably through an anti-clerical campaign. The revolts would continue up until in 1834 Santa Anna switched sides and supported a coup against Farías. Santa Anna however, not only called for Farias' overthrow, but for the dissolution of congress. On October 23, 1835, a newly elected congress voted to turn itself into a constituent congress tasked with drafting a new constitution. The resulting centralist document came to be known as the Siete Leyes, and was formally promulgated in December, 1836. Now would begin a decade of conservative and centralist rule led by Santa Anna whom the congress expected to be the first president under the new constitution.[6]

Government

Constitution of 1835: the Siete Leyes

The constitutional laws of the Mexican Republic, better known as the Seven Laws, replaced the Constitution of 1824.[7][8]

- The 15 articles of the first law granted citizenship to those who could read and had an annual income of 100 pesos, except for domestic workers, who did not have the right to vote. These centralist provisions narrowed the rights of darker, poorer, and less educated men, who had been empowered under the federal constitution.

- The second law allowed the President to close Congress and suppress the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation. Military officers were not allowed to assume this office. With these provisions there were no checks and balances, allowing the president to govern autocratically.

- The 58 articles of the third law established a bicameral Congress of Deputies and Senators, elected by governmental bodies. Deputies had four-year terms; Senators were elected for six years. Since the president had the power to dissolve congress, the legislature was a weak body.

- The 34 articles of the fourth law specified that the Supreme Court, the Senate of Mexico, and the Meeting of Ministers each nominate three candidates, and the lower house of the legislature would select from those nine candidates the President and Vice-president,

- The fifth law had an 11-member Supreme Court elected in the same manner as the President and Vice-President.

- The 31 articles of the sixth law eliminated the federal republic's states with centralized administrative departments, fashioned after the French model, whose governors and legislators were designated by the President. In the federal system, states elected their legislatures, who in turn had exercised power within the federal system.

- The seventh law prohibited a reversion to the pre-reform laws for a period of six years.

The seven laws were enacted by the interim President of Mexico, José Justo Corro, and the Congress.

Constitution of 1843: the Bases Orgánicas

In 1841, Antonio López de Santa Anna assumed the Presidency of Mexico, with extraordinary powers to govern and legislate; and he announced elections for a new Congress that would draft a new Constitution. After being elected in 1842, the Constituent Congress drafted a new Federalist constitution, much to the dislike of Santa Anna.

Because of this, Santa Anna issued a pronuncimiento which disbanded the Congress in December 1842 and replaced the Congress with a new legislative body appointed by him. This Junta Nacional Legislativa (Junta de Notables) drafted a new centralist constitution, the 1843 Bases Orgánicas, which went into effect on 12 June 1843. Santa Anna claimed the constitution was "a charter that was to facilitate popular elections, provide order, and guarantee people's rights." It further empowered the executive and "consolidated the centralist republic."[9] It furthered narrowed the franchise to vote, restricting it to adult men who earned over 200 pesos a year. Restrictions on who could belong to the Senate meant that only the wealthy, such as owners of landed estates, merchants, and miners could serve.[10]

Despite elites' wariness about electoral participation of the masses, the Bases Orgánicas sought to educate Mexico's populace within seven years, with the aim of opening male suffrage to those who were literate. Santa Anna personally had a strong commitment to education.[11] Although the Bases Orgánicas restored the Centralist government that Santa Anna wanted, the former States were awarded greater national representation and influence for their Departmental assemblies.

The Bases Orgánicas dissolved the Supreme Court and transferred those powers to the President. Elections held later that year under the Bases Orgánicas resulted in Santa Anna being re-elected as President, but the newly-elected Congress was found to be too independent for Santa Anna's comfort. When Santa Anna tried to dissolve it, the legislature claimed immunity and went into exile. Santa Anna was toppled in December 1844 by a coup of disaffected politicians, and Congress replaced Santa Anna in accordance with the Constitution of September 12, 1844, with José Joaquín de Herrera.

Herrera, recognizing the reality that Texas had been lost, tried to win his Government's recognition of the Republic of Texas as a means to prevent its annexation to the United States. In response, opponents accused Herrera of attempting to sell Texas and Alta California. On December 29, 1845, the United States annexed Texas to its territory. Mariano Paredes with the help of General Arrillaga, who was sent to secure the northern border, instead approached Mexico City, deposed De Herrera, and appointed himself as President.

History

Fall of the First Mexican Republic

In 1832, Santa Anna was elected president as a liberal and proceeded to alternate the power of the presidency with his vice-president Valentin Gomez’ Farias. The joint administration and the liberal congress elected that year attempted a series of unprecendented anti-clerical reforms triggering national backlash and scattered revolts.

Santa Anna at first rejected multiple offers to join in overthrowing Gomez Farias, but in April, 1834, as there was increasing backlash against the anti-clerical campaign, as his estate at Manga de Clavo was being flooded with pleas from all over the country to restrain Gomez Farias and Congress, and as there was ongoing infighting among Gomez Farias’ progressive supporters, Santa Anna decided in April to finally take action. [12]

The president Gomez Farias was overthrown and prominent liberal and federalist thinkers Jose Luis Mora and Lorenzo de Zavala were exiled from the nation. [13]

Santa Anna’s First Period of Rule

Santa Anna dissolved the national congress, state congresses, and replaced state governors and municipal governments with loyalists.[14][15] He however also maintained that the Constitution of 1824 was still in effect and held elections for a new congress before the end of the year. Santa Anna at this point retired to Manga de Clavo to rule from the background, as he had during the Gomez Farias administration and he was replaced by Miguel Barragan.

On October 23, 1835, the bicameral congress decreed to unite and turn itself into a constituent congress tasked with drafting a new constitution. Barragan died of typhus on February, 1836 upon which he was replaced by Jose Justo Corro. Spain and the Holy See recognized the independence of Mexico during the Corro administration. [16] Meanwhile, the resulting centralist constitution which came to be known as the Siete Leyes, and was formally promulgated in December, 1836.[17]

Certain regions of the nation however, responded to the new constitution by attempting to secede, most notably Texas.

Texas Revolution

On March 2, 1836, after a decade of failing to gain provincial autonomy, Texas declared its independence at Washington on the Brazos. Among the delegates voting for independence was the exiled Lorenzo de Zavala.[18] As the Mexican government began to lose control of the region, Santa Anna had begun to lead an army north towards Texas since November, 1835. The Battle of the Alamo ended with a Mexican victory on March 6.[19] Santa Anna, however, was routed and captured by Sam Houston at the Battle of San Jacinto on April 21. [20] Santa Anna subsequently signed a treaty recognizing Texan Independence. On July 29, 1836, the Mexican government issued a manifesto disowning Santa Anna’s arrangements and urging a continuation of the war. [21]

Meanwhile, Corro’s administration had ended and Anastasio Bustamante, who had previously been president during the First Mexican Republic was elected president in 1837. [22]

Anastasio Bustamante’s Rule

Shortly after the inauguration, news arrived that the Spanish government had recognized Mexican independence, in a treaty concluded at Madrid with the Mexican plenipotentiary, Miguel Santa Maria on December 28, 1836. The treaty was ratified by the Mexican congress on May, 1837. [23]

Pastry War

France had long been attempting to negotiate settlements of damages experienced by its citizens during Mexican conflicts. The claims of a Mexico City baker would end up giving the subsequent conflict its name. Diplomatic talks broke down on January, 1838, and French warships arrived in Veracruz on March. A French ultimatum was rejected and France declared that it would now blockade the Mexican ports. Another round of negotiations broke down and the French began to bombard Veracruz on November 27. The Fortress of San Juan de Ullua could not withstand the French artillery and surrendered the following day, and the Mexican government responded by declaring war. Santa Anna emerged from his private life at Manga del Clavo to lead troops against the French.

On December 5, three French divisions were sent to land at Veracruz to capture the forts of Santiago, Concepcion, and to arrest Santa Anna. The forts were captured, but the division tasked with finding Santa Anna was fought off at the baracks of La Merced. Santa Anna lost a leg in the fighting which gained him much public sympathy after the disgrace he suffered for losing in Texas. Nonetheless the French had effective control of Veracruz and the results of the war so far led to Bustamante’s cabinet to resign. [24]

Great Britain which also had interests in Mexico had been feeling the effects of the French blockade, and had anchored thirteen vessels in Veracruz as a show of force. France, who did not wish either to enter a conflict with England or to further invade Mexico once again entered into negotiations. An agreement was reached in April, 1838 which resulted in a French departure and a Mexican agreement to pay damages to France [25]

Urrea Federalist Rebellion

In October 1838, another rebellion against the government broke out at Tampico, and soon placed itself under the command of General Urrea who intended to restore the federalist system. The revolt rapidly spread, and the rebels now succeeded in overthrowing the governors of Monterey and Nuevo Leon and in March, 1839 government reinforcements under General Cos were routed. [26]

Bustamante stepped down from the presidency and assumed command of the armed forces himself. The presidency in the meantime was held by Santa Anna who had been rehabilitated by his role in the Pastry War. Government forces defeated the rebels at the Battle of Acajete on May 3, 1839. Urrea however escaped and retreated into Tampico which fell to government forces on June 11 with Urrea being exiled.[27]

Loss of Yucatan

Bustamante would now go on to face the most serious separatist crisis the country had experienced since the Texas Revolution. Years of frustration with exise taxes, levies, conscription, and increase of custom duties culminated in the standard of revolt being raised at Tizimin on May, 1839. Valladolid was captured in February, 1840 and joined by Merida. The entire north-east of the Yucatan Peninsula declared itself independent until Mexico should restore the federal system. Campeche was captured on June 6, and now the entire peninsula was in the hands of the rebels, who proceeded to elect a legislature and form an alliance with Texas[28]

Gomez Farias Federalist Rebellion

Bustamante was not able to suppress the Yucatan movement and its success inspired the federalists to renew their struggle. General Urrea had been arrested but continued to conspire with his associates and on July 15, 1840, he was broken out of prison. With a group of select men, Urrea broke into the National Palace, and took Bustamante hostage. Juan Almonte, the minister of war had meanwhile escaped to organize a rescue.[29]

Valentin Gomez Farias, the exiled last president of the First Mexican Republic, had now arrived in the country to take command of the revolt. Government and federalist forces now converged at the capital. Federalists occupied the entire vicinity of the National Palace while government forces prepared their positions for an attack. Skirmishes broke out the entire afternoon, sometimes involving artillery. [30]

The conflict appeared to be reaching a stalemate, and the president was released in order to try and reach a negotiation. Negotiations broke down and the capital had to face twelve days of warfare, which resulted in property damage, civilian loss of life, and a large exodus of refugees out of the city. [31] Now news was received that government reinforcements were on the way under the command of Santa Anna. Rather than face a protracted conflict that would destroy the capital, negotiations were started again and an agreement was reached whereby there would be a ceasefire, and the rebels would be granted amnesty.[32]

Bustamante’s Overthrow

In response to national financial and political crises, Mariano Paredes on August 8, 1841, published a manifesto to his fellow commander generals, calling for the creation of a new government. He gathered as many troops as he could, gathered more on the way and entered the city of Tacubaya where he was joined by Santa Anna. In September, Bustamante resigned the presidency once again to lead the troops personally and left the presidency to the finance minister Javier Echeverria. He attempted to proclaim support for the federal system in order to divide his enemies, but the ploy failed. The insurgents were triumphant and Bustamante officially surrendered power through the Estanzuela Accords on October 6, 1841.

A military junta was formed which wrote the Bases of Tacubaya, a plan which swept away the entire structure of government, except the judiciary, and also called for elections for a new constituent congress meant to write a new constitution. Santa Anna then placed himself at the head of a provisional government.[33]

Santa Anna’s Second Period of Rule

Unfortunately for Santa Anna and his centralist allies, the subsequently elected congress, installed on June, 10, 1842 was strongly federalist. Santa Anna began to scheme to dissolve the congress, and left Nicolas Bravo in charge of the presidency on October 26, 1842. [34] Congress was dissolved on December 19, 1842, and replaced by a centralist Junta of Notables.[35] The Junta produced a new constitution known as the Bases Orgánicas on June 12, 1843.

By mid 1844 there were rising tensions with the United States over the matter of Texas, and a series of forced loans had resulted in much disaffection. Paredes who had previously played a key role in overthrowing Bustamante, was considering once again leading a revolution.[36] Paredes proclaimed against the government in Guadalajara and was joined by the north of the country.[37]

Without the authorization of congress, Santa Anna led an army north against the revolt and overthrew the government of Queretaro. The nominal president at this time was Valentin Canalizo, though under the influence of Santa Anna. Congress condemned Santa Anna for having assumed military command without their authority. The ministers were censured by congress for allowing Santa Anna to imprison the Departmental Assembly of Queretaro and for replacing its governor. The Canalizo administration responded by having congress shut down, and explaining that its measures were necessary given the ongoing emergency of a potential American annexation of Texas.

This led to a military uprising against the government in the capital. Canalizo resigned and on December 6, 1844, congress was restored and Jose Joaquin Herrera was installed as the new president with a new ministry. The country was now divided into three loyalties between Herrera’s central government, Santa Anna’s military forces, and Mariano Paredes’ military forces.[38]

Paredes and Herrera joined forces and headed against Santa Anna . With the opposing forces about evenly matched, Santa Anna attempted to open negotiations, but Herrera would accept nothing less than unconditional surrender, and Santa Anna began plans to flee the country, only to be arrested near the town of Jico.[39]

Mexican-American War

Herrera Administration

As relations worsened with the United States, President Herrera had conceded the possibility of recognizing Texan independence as long as there was no annexation, but this was perceived by his opponents as an alienation of Mexican territory. Mariano Paredes issued a pronunciamiento in December, 1845 calling for the overthrow of the government[40] .President Herrera was not able to gather much support and resigned on December 30, 1845. Paredes and his forces entered the capital three days later.[41]

Paredes Administration

On January 3 Mariano Paredes ascended to the presidency. [42] On January 26, 1846, an official government convocation was decreed summoning an extraordinary congress with the power to make constitutional changes. It was to be made up of 160 deputies, organized on a corporatist basis, representing not geographical areas, but nine classes: land owners, merchants, miners, manufacturers, literary men, magistrates, public functionaries, clergy, and army, elected by the members of those classes. [43]

The United States had annexed Texas in December, 1845 and troops led by Zachary Taylor had begun to patrol territory that Mexico still claimed. Mexican troops clashed with American troops on the Rio Grande in April, and the United States declared war.

In the first few months of the war, the Paredes administration was confronted with a catastrophic series of losses. Mexicon forces were defeated at the Battle of Palo Alto and the Battle of Resaca de la Palma. U.S. forces under Zachary Taylor had crossed the Rio Grande, and undefeated through a series of battles made it as far south as Saltillo. Meanwhile American forces were seizing California.

The constituent congress met on July 28 and initially ratified Paredes as president and granted him emergency powers, but as the course of the war inflamed opposition against the government, and Paredes faced revolution, he resigned on July 28, choosing to return to the military to help with the war effort. [44]

Restoration of the Federalist System

On August 3, the garrisons of Vera Cruz and San Juan de Ulua revolted, proclaiming the plan of Guadalajara. Mariano Salas was made the provisional president, and on August 22 restored the Constitution of 1824, putting an end to Centralist Republic of Mexico.[45]

Armed opposition to the Central Republic

.svg.png.webp)

The conservatives' attempt to impose a unitary state produced armed resistance in regions that had most favored federalism. Centralism generated severe political instability, armed uprisings and secessions: The rebellions in Zacatecas, Alta California, Sonora, New Mexico, the Texas Revolution, the separation of Tabasco, the independence of Coahuila, Nuevo León and Tamaulipas that formed the Republic of the Rio Grande, and finally the independence of the state of Yucatán.

The Mexican Federalist War (armed opposition to the central republic) involved series of armed conflicts and political machinations between the Centrists and the Federalists.[46] Superficially the war can be viewed as a conflict between rival generals,[47] however the Centrist position favored a presidency that reflected the viceregal tradition of Spanish colonial times.[48] and the Federalists supported republicanism and local self-government (which in some cases such as Texas led ultimately to secession from Mexico).[47] Centrists tended to draw support from the privileged classes including prominent members of the Roman Catholic Church and professional officers of the Mexican army. They were in favor of a strong, central government and Roman Catholicism as the established church.[48]

Rebellion in Zacatecas

Zacatecas, a silver mining center in Mexico's north, was a strong proponent of federalism. The revolt in Zacatecas was the first rebellion to erupt as a reaction to the formation of the Central Republic. The rebellion began as a response to the order of the Central Government dissolving the State militias, which had been a foundation of state power. Zacatecas had previously been a supporter of Santa Anna in the political struggles of 1832 against conservative Anastasio Bustamante. Santa Anna himself led the Mexican army against the Zacatecas rebels, who were led by Governor Francisco García Salinas. Zacatecas had a militia of about four thousand men against the Central Government. In one of his many absences that were to come, Santa Anna left the Presidency to General Miguel Barragán. Likely Santa Anna did not want any state to challenge the power of the new central government and the army, but historian Will Fowler suggests that Santa Anna "expected his allies to be faithful even if he changed sides" when they did not support the Plan of Cuernavaca.[49] Governor García Salinas and his army were defeated in the 1835 Battle of Zacatecas.[50] As punishment for rebellious Zacatecas, the region of Aguascalientes was separated from Zacatecas and declared on 23 May 1835 to be Federation territory. Santa Anna's troops pillaged Zacatecas, and left the region embittered against him, but Zacatecos who surrendered to Santa Anna's forces were allowed to go free. Santa Anna himself profited from the conquest, carting off silver from the Fresnillo mine and distributing some of it to his friends, such as José María Tornel, with the Mexican treasury losing 180,000 pesos.[51]

Texan independence

The Texan Revolution began with the Battle of Gonzales on October 2, 1835. The discontent of the Anglo-American settlers had begun almost as soon as they began settling in Coahuila y Tejas in the 1820s. Many were from the slave-owning southern region of the US, so that the abolition of slavery in Mexico during the presidency of Vicente Guerrero was abhorrent. The rebellion of 1827 of Fredonia (in eastern Texas) led to the government issuing the Law of April 6, 1830 that increased the discontent of the colonists due to its attempts to restrict further US American immigration into Texas, among other things.

In 1831, the Mexican authorities provided the town of González with a small cannon to help protect themselves from frequent Comanche raids. As a consequence of the order of the government to dissolve the state militias, Colonel Domingo Ugartechea, Commander of Mexican troops in Texas, sent a small group of soldiers to González to reclaim the cannon. On October 1, settlers voted to refuse the request, even defending it by force if necessary. The standoff ended the next day without violence with the withdrawal of Colonel Ugartechea's soldiers.

After González residents' victory and later, the unsuccessful Siege of Béxar, the Central government won a series of victories against the region's settlers, most of them commanded by General José de Urrea. On February 23, 1836, the Army of Operations in Texas, headed by President Antonio López de Santa Anna, began the siege of the Alamo. Most of the soldiers involved in the siege had been recruited against their will. Nonetheless, The Alamo fell two weeks later on March 6, resulting in the deaths of all but two of the Texans defending the mission.

On April 21, the Battle of San Jacinto (also known as "La Siesta del San Jacinto") took place, where the Mexican army was attacked while sleeping and was totally defeated. Santa Anna was captured days after the battle and signed under duress the Treaties of Velasco, which recognized the independence of Texas on May 14. The Mexican government headed by José Justo Corro did not recognize the treaty, maintaining that Santa Anna had no authority to grant independence to the territory. Despite that, Texas remained de facto independent until 1845, when it was annexed to United States.

Rebellion in northeastern Mexico

The Republic of the Rio Grande was a proposed republic composed of the Mexican states of Coahuila, Nuevo León, Tamaulipas and parts of the current U.S. state of Texas. On 17 January 1840, a group of notables of the three states met close to Laredo. They planned a secession from Mexico and the formation of their own federal republic composed of the three states, with Laredo as the capital. However, the legislatures of the states (then departments) did not take any constitutional action to support the creation of the new republic and instead asked the central government for help to quell the rebellion. The insurgents, in turn, asked for help from the president of the Republic of Texas, Mirabeau B. Lamar, who gave them no support because Texas was looking for the recognition of its own independence from Mexico.

Finally, after a series of defeats, on 6 November 1840, Antonio Canales, Commander in Chief of the insurgent army, met with Mexican General Mariano Arista, who offered him the post of Brigadier General of the Mexican army to entice Canales to abandon his loyalty to the secessionists. Canales accepted the offer, and the bid for independence was ended.

Rebellion in California

In 1836, supporters of federalism in Alta California, under the leadership of Monterey-born Juan Bautista Alvarado, revolted against the Centralist Republic and succeeded in removing the Centralist Republic interim Governor of California, Nicolás Gutiérrez, from office. With the support of other Californio politicians such as José Castro and Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, Alvarado named himself the new governor of California and called a territorial congress which adopted a program known as the Monterey Plan that declared Alta California as an independent nation until the reinstatement of the Mexican constitution of 1824.[52] In 1837 the Mexican government named Carlos Antonio Carrillo as the new governor of California, and the citizens of Los Angeles rose in opposition to the rebels taking oaths of loyalty to the Centralist government.[52]: 105 However when Carrillo attempted to assert his rule as governor by marching northwards in 1838 he was defeated by Alvarado's forces in minor skirmishes at Las Flores and San Buenaventura and then captured.[52]: 106 The citizens of Los Angeles were then called into a public assembly and the ayuntamiento voted to recognize Alvaroda as the legitimate governor of California.[52]: 107 The Mexican government responded by recognizing Alvarado's governorship in 1839 after which the Californian population, now satisfied that it had a strong governor that would represent its interests, ended its bid for independence.[52]: 107

Rebellion in New Mexico

On 1 August 1837 in Santa Cruz, New Mexico, a popular revolution against the Mexican Centralist Republic Governor Albino Pérez took place due in large part to widespread opposition to the governor's ineffective policies towards custom officials, who according to the revolutionaries were using corrupt taxation practices in order to take advantage of the lucrative Santa Fe Trail trade. Pérez attempted to raise a militia in response but on 8 August he was decapitated in a raid by a group of Indians and his head was taken to be displayed in public in Santa Fe. Along with Pérez at least 20 other government officials were killed and a new "popular junta" government was proclaimed. This government proved unpopular and a counterrevolutionary movement led by previous New Mexican governor and Albuquerque native Manuel Armijo rose in response with Armijo winning consecutive military victories and writing to the Mexican Central government requesting support and additional troops to quell the uprising. The rebellion would last until January 1838 with Armijo defeating the rebel leader José Gonzales in battle and proceeding to have the rebel leader publicly executed in Santa Cruz.

Rebellion in northwestern Mexico

In December 1837 former Mexican General José de Urrea, a veteran of the Texas Rebellion on the Mexican side, turned against the Centralist government and began a pro-federalist revolt in Sonora with the intention of reestablishing the 1824 Constitution of Mexico as the law of the land. With the support of federalist politicians in Sonora, Urrea gathered followers and traveled to Sinaloa in hopes of appealing to the federalist politicians there as well. However, he was instead intercepted and defeated in Sinaloa by Centralist government forces and was taken prisoner effectively ending the rebellion in Sonora and Sinaloa.

Rebellion in Tabasco

The Tabasco rebellion started in 1839. Like the other rebellions, it was led by Federalist rebels who opposed the Centralist government being implemented in Mexico. The rebels took several major cities and also asked for aid from the Government of Texas, who supported them with two boats. This rebellion culminated in January 1841, with the triumph of the Federalists and the fall of the Centralist Governor José Ignacio Gutiérrez.

The then-Mexican President Anastasio Bustamante, in retaliation for this rebellion, closed the port of San Juan Bautista, which affected the economic life of the territory. This caused further agitation among the Federalist Tabasco authorities, who then on February 13, 1841, declared Tabasco's independence from Mexico.

Months later, Antonio López de Santa Anna, in response to the declaration of independence, threatened to send in the troops if it was not reversed while also assuring the Tabasco authorities that Federalism would soon be reinstated. This combined threat and promise culminated in the reinstatement of Tabasco into the Mexican Republic on December 2, 1842. But four years later, Tabasco again declared its independence in November 1846 as a protest to the lack of Central government assistance in resisting the American occupation of its coast earlier that same year.

Independence of Yucatán

Yucatán joined the Federation in 1823 under a special status, the Federated Republic, as stipulated by the Constitution of Yucatán of 1825.

When the Federal system was changed to a Centralist system, Yucatán considered their pact with Mexico dissolved. After several demands by Yucatán to the Central government to restore the Federalist Constitution of 1824, revolution broke out in Yucatán on 29 May 1839. After a series of victories by the Yucatán militia against Mexican Army installations and troops, the Central Government declared war on Yucatán. On 4 March 1840, the Congress of Yucatan decreed that as long as the Mexican nation is not governed according to federal law, the State of Yucatán would remain separated from it, retaining the power to establish its own legislature.

On March 31, 1841, a new constitution of Yucatán was enacted, which established innovations such as freedom of worship, freedom of the press and the constitutional and legal bases of the Writ of Amparo. On October 1, 1841, the Chamber of Deputies of Yucatán issued the Act of Independence of the Yucatán Peninsula.

Santa Anna sent retired Mexican Supreme Court Justice and revolutionary hero Andrés Quintana Roo to dialogue with the Yucatecan authorities to negotiate their return to Mexico. The meeting resulted in signed treaties that were beneficial for Yucatán, and which were later rejected by Santa Anna. Santa Anna then sent Mexican troops to Yucatán to quell the rebellion, but his troops were defeated. Having failed to subdue the peninsula, Santa Anna then imposed a trade blockade. The blockade forced the Yucatecan authorities to negotiate with Santa Anna. On 5 December 1843, new treaties were signed that restored Yucatán relations with Mexico, but Yucatán continued to govern itself under its own laws and leaders. In 1845, Mexican President José Joaquín de Herrera set aside those treaties and again raised tensions between Yucatán and Mexico.

After Federalism was restored in 1846, Yucatán decided to rejoin Mexico, but a considerable minority opposed the reinstatement due to the U.S. invasion of Mexico in the Mexican–American War (1846–48). On 30 July 1847, Yucatán's Maya population rebelled in a conflict now known as the Caste War. The war forced Yucatán to seek help from Mexico, which negotiated their return to the Republic, which took place on 17 August 1848. The conflict in Yucatan was largely contained, with the Yucatecan government declaring victory. However, pockets of resistance continued to exist for another 50 years, when Mexican army troops destroyed the last Maya stronghold.

The flag of the Republic of Yucatán, created as part of its declaration of independence from Mexico, is still widely used as a civil emblem in the state and there are proposals even today to adopt it as the official state flag.

Engraved stone tells a few episodes of the Caste War between 1854 and 1855. Although the Centralist regime had already formally disappeared by that time, the stone still mentions the "Department of YUCATÁN".

References

- "Portal Politico del Ciudadano INEP, A. C." INEP.org. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- Michael P. Costeloe, The Central Republic in Mexico and the 'Hombres de bien in the Age of Santa Anna. Cambridge University Press 1993.

- Costeloe, The Central Republic in Mexico, 1835-1846. Hombres de Bien in the Age of Santa Anna.

- Priestly, Joseph (1864). The Mexican Nation: A History. p. 261.

- Priestly, Joseph (1864). The Mexican Nation: A History. p. 263.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. Bancroft Company. pp. 144–145.

- Felipe Tena Ramírez, Leyes fundamentales de México, 1808-1971. pp. 202–248.

- Michael P. Costeloe, "Siete Leyes (1836)" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 4, p. 25. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- Fowler, Santa Anna of Mexico, p. 215.

- Fowler, Santa Anna of Mexico p. 216.

- Fowler, Santa Anna of Mexico, pp. 217-18.

- Zamacois, Niceto (1880). Historia de Mexico Tomo XII (in Spanish). JF Parres. pp. 44–45.

- Parkes, Henry (1938). A History of Mexico. Houghton Mifflin. p. 197.

- Parkes, Henry (1938). A History of Mexico. Houghton Mifflin. p. 197.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. Bancroft Company. p. 141.

- Bazant, "From Independence to the Liberal Republic, 1821-1867" p. 16.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. Bancroft Company. pp. 144–145.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. Bancroft Company. p. 165.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. Bancroft Company. pp. 167–168.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. Bancroft Company. p. 171.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. Bancroft Company. pp. 173–174.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. Bancroft Company. p. 179.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 181.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. pp. 198–200.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. pp. 202–204.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. pp. 209–210.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. pp. 209–212.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. pp. 218–219.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. pp. 218–219.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 221.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 222.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 223.

- Rivera Cambas, Manueldate=1873. Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II. J.M. Aguilar Cruzpages=287.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 254.

- Rivera Cambas, Manueldate=1873. Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II. J.M. Aguilar Cruzpages=250.

- Rivera Cambas, Manueldate=1873. Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II. J.M. Aguilar Cruzpages=288.

- Rivera Cambas, Manueldate=1873. Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II. J.M. Aguilar Cruzpages=288.

- Rivera Cambas, Manueldate=1873. Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II. J.M. Aguilar Cruzpages=288.

- Rivera Cambas, Manueldate=1873. Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II. J.M. Aguilar Cruzpages=288.

- Rivera Cambas, Manueldate=1873. Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II. J.M. Aguilar Cruzpages=288.

- Rivera Cambas, Manueldate=1873. Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II. J.M. Aguilar Cruzpages=289.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 293.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 295.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 299.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. pp. 299–300.

- Jaques, Tony, ed. (2007), Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A Guide to 8,500 Battles from Antiquity through the Twenty-first Century (3 volumes page ed.), Greenwood Publishing Group, pp. 5, p. 5, 890, 907, 993–994, ISBN 978-0-313-33536-5

- Mann, James Saumarez (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 339.

- "Mexico - Independence: Early Republic". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Fowler, Santa Anna of Mexico, p. 159.

- Bazant, Jan. "From Independence to the Liberal Republic, 1821-1867" in Mexico since Independence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1991, p. 15.

- Fowler, Santa Anna of Mexico, p. 160.

- James Miller Guinn (1906). History of the State of California and Biographical Record of the Sacramento Valley, California: An Historical Study of the State's Marvelous Growth from Its Earliest Settlement to the Present Time. Chapman Publishing Company. pp. 102–3.

Further reading

- Barker, Nancy. The French Experience in Mexico, 1821-1861. University of North Carolina Press 2011. ISBN 978-0807896150

- Calcott, Wilfred H. Santa Anna: The Story of the Enigma Who Once Was Mexico. Hamden CT: Anchon 1964.

- Costeloe, Michael P. The Central Republic in Mexico, 1835-1846: Hombres de Bien in the Age of Santa Anna. Cambridge University Press 1993. ISBN 978-0521530644

- Fowler, Will. Santa Anna of Mexico. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 2007. ISBN 978-0-8032-1120-9

- Hale, Charles A. Mexican Liberalism in the Age of Mora, 1821-1853. New Haven: Yale University Press 1968. ISBN 978-0300005318

- Van Young, Eric. Stormy Passage: Mexico from Colony to Republic, 1750-1850. Lanham MD: Rowman and Littlefield 2022. ISBN 9781442209015