Group 7 element

Group 7, numbered by IUPAC nomenclature, is a group of elements in the periodic table. They are manganese (Mn), technetium (Tc), rhenium (Re), and bohrium (Bh). All known elements of group 7 are transition metals.

| Group 7 in the periodic table | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| ↓ Period | |||||||||

| 4 |  25 Transition metal | ||||||||

| 5 |  43 Transition metal | ||||||||

| 6 |  75 Transition metal | ||||||||

| 7 | Bohrium (Bh) 107 Transition metal | ||||||||

|

Legend

| |||||||||

Like other groups, the members of this family show patterns in their electron configurations, especially the outermost shells resulting in trends in chemical behavior.

Chemistry

Like other groups, the members of this family show patterns in its electron configuration, especially the outermost shells:

| Z | Element | No. of electrons/shell |

|---|---|---|

| 25 | manganese | 2, 8, 13, 2 |

| 43 | technetium | 2, 8, 18, 13, 2 |

| 75 | rhenium | 2, 8, 18, 32, 13, 2 |

| 107 | bohrium | 2, 8, 18, 32, 32, 13, 2 |

Bohrium has not been isolated in pure form.

History

Manganese was discovered much earlier than the other group 7 elements owing to its much larger abundance in nature. While Johan Gottlieb Gahn is credited with the isolation of manganese in 1774, Ignatius Kaim reported his production of manganese in his dissertation in 1771.[1]

Group 7 contains the two naturally occurring transition metals discovered last: technetium and rhenium. Rhenium was discovered when Masataka Ogawa found what he thought was element 43 in thorianite, but this was dismissed; recent studies by H. K. Yoshihara suggest that he discovered rhenium instead, a fact not realized at the time. Walter Noddack, Otto Berg, and Ida Tacke were the first to conclusively identify rhenium;[2] it was thought they discovered element 43 as well, but as the experiment could not be replicated, it was dismissed. Technetium was formally discovered in December 1936 by Carlo Perrier and Emilio Segré, who discovered technetium-95 and technetium-97. Bohrium was discovered in 1981 by a team led by Peter Armbruster and Gottfried Münzenburg by bombarding bismuth-209 with chromium-54.

Occurrence and production

Manganese

Manganese comprises about 1000 ppm (0.1%) of the Earth's crust, the 12th most abundant of the crust's elements.[3] Soil contains 7–9000 ppm of manganese with an average of 440 ppm.[3] The atmosphere contains 0.01 μg/m3.[3] Manganese occurs principally as pyrolusite (MnO2), braunite (Mn2+Mn3+6)(SiO12),[4] psilomelane (Ba,H2O)2Mn5O10, and to a lesser extent as rhodochrosite (MnCO3).

The most important manganese ore is pyrolusite (MnO2). Other economically important manganese ores usually show a close spatial relation to the iron ores, such as sphalerite.[6][7] Land-based resources are large but irregularly distributed. About 80% of the known world manganese resources are in South Africa; other important manganese deposits are in Ukraine, Australia, India, China, Gabon and Brazil.[5] According to 1978 estimate, the ocean floor has 500 billion tons of manganese nodules.[8] Attempts to find economically viable methods of harvesting manganese nodules were abandoned in the 1970s.[9]

In South Africa, most identified deposits are located near Hotazel in the Northern Cape Province, with a 2011 estimate of 15 billion tons. In 2011 South Africa produced 3.4 million tons, topping all other nations.[10]

Manganese is mainly mined in South Africa, Australia, China, Gabon, Brazil, India, Kazakhstan, Ghana, Ukraine and Malaysia.[11]

For the production of ferromanganese, the manganese ore is mixed with iron ore and carbon, and then reduced either in a blast furnace or in an electric arc furnace.[12] The resulting ferromanganese has a manganese content of 30 to 80%.[6] Pure manganese used for the production of iron-free alloys is produced by leaching manganese ore with sulfuric acid and a subsequent electrowinning process.[13]

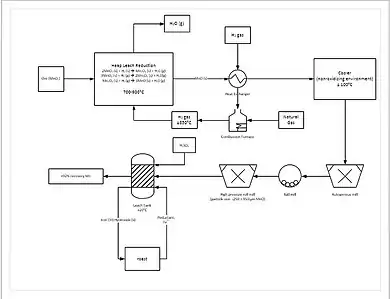

A more progressive extraction process involves directly reducing (a low grade) manganese ore in a heap leach. This is done by percolating natural gas through the bottom of the heap; the natural gas provides the heat (needs to be at least 850 °C) and the reducing agent (carbon monoxide). This reduces all of the manganese ore to manganese oxide (MnO), which is a leachable form. The ore then travels through a grinding circuit to reduce the particle size of the ore to between 150 and 250 μm, increasing the surface area to aid leaching. The ore is then added to a leach tank of sulfuric acid and ferrous iron (Fe2+) in a 1.6:1 ratio. The iron reacts with the manganese dioxide (MnO2) to form iron(III) oxide-hydroxide (FeO(OH)) and elemental manganese (Mn):

This process yields approximately 92% recovery of the manganese. For further purification, the manganese can then be sent to an electrowinning facility.[14]

In 1972 the CIA's Project Azorian, through billionaire Howard Hughes, commissioned the ship Hughes Glomar Explorer with the cover story of harvesting manganese nodules from the sea floor.[15] That triggered a rush of activity to collect manganese nodules, which was not actually practical. The real mission of Hughes Glomar Explorer was to raise a sunken Soviet submarine, the K-129, with the goal of retrieving Soviet code books.[16]

An abundant resource of manganese in the form of Mn nodules found on the ocean floor.[17][18] These nodules, which are composed of 29% manganese,[19] are located along the ocean floor and the potential impact of mining these nodules is being researched. Physical, chemical, and biological environmental impacts can occur due to this nodule mining disturbing the seafloor and causing sediment plumes to form. This suspension includes metals and inorganic nutrients, which can lead to contamination of the near-bottom waters from dissolved toxic compounds. Mn nodules are also the grazing grounds, living space, and protection for endo- and epifaunal systems. When theses nodules are removed, these systems are directly affected. Overall, this can cause species to leave the area or completely die off.[20] Prior to the commencement of the mining itself, research is being conducted by United Nations affiliated bodies and state-sponsored companies in an attempt to fully understand environmental impacts in the hopes of mitigating these impacts.[21]

Technetium

Technetium was created by bombarding molybdenum atoms with deuterons that had been accelerated by a device called a cyclotron. Technetium occurs naturally in the Earth's crust in minute concentrations of about 0.003 parts per trillion. Technetium is so rare because the half-lives of 97Tc and 98Tc are only 4.2 million years. More than a thousand of such periods have passed since the formation of the Earth, so the probability of survival of even one atom of primordial technetium is effectively zero. However, small amounts exist as spontaneous fission products in uranium ores. A kilogram of uranium contains an estimated 1 nanogram (10−9 g) equivalent to ten trillion atoms of technetium.[22][23][24] Some red giant stars with the spectral types S-, M-, and N contain a spectral absorption line indicating the presence of technetium.[25][26] These red giants are known informally as technetium stars.

Rhenium

Rhenium is one of the rarest elements in Earth's crust with an average concentration of 1 ppb;[27][2] other sources quote the number of 0.5 ppb making it the 77th most abundant element in Earth's crust.[28] Rhenium is probably not found free in nature (its possible natural occurrence is uncertain), but occurs in amounts up to 0.2%[27] in the mineral molybdenite (which is primarily molybdenum disulfide), the major commercial source, although single molybdenite samples with up to 1.88% have been found.[29] Chile has the world's largest rhenium reserves, part of the copper ore deposits, and was the leading producer as of 2005.[30] It was only recently that the first rhenium mineral was found and described (in 1994), a rhenium sulfide mineral (ReS2) condensing from a fumarole on Kudriavy volcano, Iturup island, in the Kuril Islands.[31] Kudriavy discharges up to 20–60 kg rhenium per year mostly in the form of rhenium disulfide.[32][33] Named rheniite, this rare mineral commands high prices among collectors.[34]

Most of the rhenium extracted comes from porphyry molybdenum deposits.[35] These ores typically contain 0.001% to 0.2% rhenium.[27] Roasting the ore volatilizes rhenium oxides.[29] Rhenium(VII) oxide and perrhenic acid readily dissolve in water; they are leached from flue dusts and gasses and extracted by precipitating with potassium or ammonium chloride as the perrhenate salts, and purified by recrystallization.[27] Total world production is between 40 and 50 tons/year; the main producers are in Chile, the United States, Peru, and Poland.[36] Recycling of used Pt-Re catalyst and special alloys allow the recovery of another 10 tons per year. Prices for the metal rose rapidly in early 2008, from $1000–$2000 per kg in 2003–2006 to over $10,000 in February 2008.[37][38] The metal form is prepared by reducing ammonium perrhenate with hydrogen at high temperatures:[39]

- 2 NH4ReO4 + 7 H2 → 2 Re + 8 H2O + 2 NH3

- There are technologies for the associated extraction of rhenium from productive solutions of underground leaching of uranium ores.[40]

Bohrium

Bohrium is a synthetic element that does not occur in nature. Very few atoms have been synthesized, and also due to its radioactivity, only limited research has been conducted. Bohrium is only produced in nuclear reactors and has never been isolated in pure form.

Applications

The facial isomer of both rhenium and manganese 2,2'-bipyridyl tricarbonyl halide complexes have been extensively researched as catalysts for electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction due to their high selectivity and stability. They are commonly abbreviated as M(R-bpy)(CO)3X where M = Mn, Re; R-bpy = 4,4'-disubstituted 2,2'-bipyridine; and X = Cl, Br.

Rhenium

The catalytic activity of Re(bpy)(CO)3Cl for carbon dioxide reduction was first studied by Lehn et al.[41] and Meyer et al.[42] in 1984 and 1985, respectively. Re(R-bpy)(CO)3X complexes exclusively produce CO from CO2 reduction with Faradaic efficiencies of close to 100% even in solutions with high concentrations of water or Brønsted acids.[43]

The catalytic mechanism of Re(R-bpy)(CO)3X involves reduction of the complex twice and loss of the X ligand to generate a five-coordinate active species which binds CO2. These complexes will reduce CO2 both with and without an additional acid present; however, the presence of an acid increases catalytic activity.[43] The high selectivity of these complexes to CO2 reduction over the competing hydrogen evolution reaction has been shown by density functional theory studies to be related to the faster kinetics of CO2 binding compared to H+ binding.[44]

Manganese

The rarity of rhenium has shifted research toward the manganese version of these catalysts as a more sustainable alternative.[43] The first reports of catalytic activity of Mn(R-bpy)(CO)3Br towards CO2 reduction came from Chardon-Noblat and coworkers in 2011.[45] Compared to Re analogs, Mn(R-bpy)(CO)3Br shows catalytic activity at lower overpotentials.[44]

The catalytic mechanism for Mn(R-bpy)(CO)3X is complex and depends on the steric profile of the bipyridine ligand. When R is not bulky, the catalyst dimerizes to form [Mn(R-bpy)(CO)3]2 before forming the active species. When R is bulky, however, the complex forms the active species without dimerizing, reducing the overpotential of CO2 reduction by 200-300 mV. Unlike Re(R-bpy)(CO)3X, Mn(R-bpy)(CO)3X only reduces CO2 in the presence of an acid.[44]

Technetium

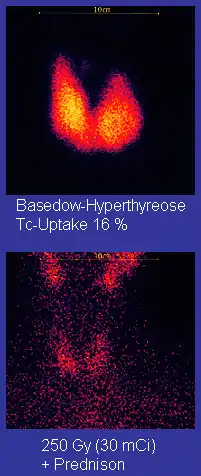

Technetium-99m ("m" indicates that this is a metastable nuclear isomer) is used in radioactive isotope medical tests. For example, Technetium-99m is a radioactive tracer that medical imaging equipment tracks in the human body.[22][46][47] It is well suited to the role because it emits readily detectable 140 keV gamma rays, and its half-life is 6.01 hours (meaning that about 94% of it decays to technetium-99 in 24 hours).[48] The chemistry of technetium allows it to be bound to a variety of biochemical compounds, each of which determines how it is metabolized and deposited in the body, and this single isotope can be used for a multitude of diagnostic tests. More than 50 common radiopharmaceuticals are based on technetium-99m for imaging and functional studies of the brain, heart muscle, thyroid, lungs, liver, gall bladder, kidneys, skeleton, blood, and tumors.[49] Technetium-99m is also used in radioimaging.[50]

The longer-lived isotope, technetium-95m with a half-life of 61 days, is used as a radioactive tracer to study the movement of technetium in the environment and in plant and animal systems.[51]

Technetium-99 decays almost entirely by beta decay, emitting beta particles with consistent low energies and no accompanying gamma rays. Moreover, its long half-life means that this emission decreases very slowly with time. It can also be extracted to a high chemical and isotopic purity from radioactive waste. For these reasons, it is a National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) standard beta emitter, and is used for equipment calibration.[52] Technetium-99 has also been proposed for optoelectronic devices and nanoscale nuclear batteries.[53]

Like rhenium and palladium, technetium can serve as a catalyst. In processes such as the dehydrogenation of isopropyl alcohol, it is a far more effective catalyst than either rhenium or palladium. However, its radioactivity is a major problem in safe catalytic applications.[54]

When steel is immersed in water, adding a small concentration (55 ppm) of potassium pertechnetate(VII) to the water protects the steel from corrosion, even if the temperature is raised to 250 °C (523 K).[55] For this reason, pertechnetate has been used as an anodic corrosion inhibitor for steel, although technetium's radioactivity poses problems that limit this application to self-contained systems.[56] While (for example) CrO2−

4 can also inhibit corrosion, it requires a concentration ten times as high. In one experiment, a specimen of carbon steel was kept in an aqueous solution of pertechnetate for 20 years and was still uncorroded.[55] The mechanism by which pertechnetate prevents corrosion is not well understood, but seems to involve the reversible formation of a thin surface layer (passivation). One theory holds that the pertechnetate reacts with the steel surface to form a layer of technetium dioxide which prevents further corrosion; the same effect explains how iron powder can be used to remove pertechnetate from water. The effect disappears rapidly if the concentration of pertechnetate falls below the minimum concentration or if too high a concentration of other ions is added.[57]

As noted, the radioactive nature of technetium (3 MBq/L at the concentrations required) makes this corrosion protection impractical in almost all situations. Nevertheless, corrosion protection by pertechnetate ions was proposed (but never adopted) for use in boiling water reactors.[57]

Bohrium

Bohrium is a synthetic element and is too radioactive to be used in anything.

Precautions

Although being an essential trace element in the human body, manganese can be somewhat toxic if ingested in higher amounts than normal. Technetium should be handled with care due to its radioactivity.

Biological role and precautions

Only manganese has a role in the human body. It is an essential trace nutrient, with the body containing approximately 10 milligrams at any given time, being mainly in the liver and kidneys. Many enzymes contain manganese, making it essential for life, and is also found in chloroplasts. Technetium, rhenium, and bohrium have no known biological roles. Technetium is, however, used in radioimaging.

References

- "Manganese - Element information, properties and uses | Periodic Table". www.rsc.org. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- "Rhenium - Element information, properties and uses | Periodic Table". www.rsc.org. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- Emsley, John (2001). "Manganese". Nature's Building Blocks: An A-Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 249–253. ISBN 978-0-19-850340-8.

- Bhattacharyya, P. K.; Dasgupta, Somnath; Fukuoka, M.; Roy Supriya (1984). "Geochemistry of braunite and associated phases in metamorphosed non-calcareous manganese ores of India". Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 87 (1): 65–71. Bibcode:1984CoMP...87...65B. doi:10.1007/BF00371403. S2CID 129495326.

- USGS Mineral Commodity Summaries 2009

- Holleman, Arnold F.; Wiberg, Egon; Wiberg, Nils (1985). "Mangan". Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie (in German) (91–100 ed.). Walter de Gruyter. pp. 1110–1117. ISBN 978-3-11-007511-3.

- Cook, Nigel J.; Ciobanu, Cristiana L.; Pring, Allan; Skinner, William; Shimizu, Masaaki; Danyushevsky, Leonid; Saini-Eidukat, Bernhardt; Melcher, Frank (2009). "Trace and minor elements in sphalerite: A LA-ICPMS study". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 73 (16): 4761–4791. Bibcode:2009GeCoA..73.4761C. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2009.05.045.

- Wang, X; Schröder, HC; Wiens, M; Schlossmacher, U; Müller, WEG (2009). "Manganese/polymetallic nodules: micro-structural characterization of exolithobiontic- and endolithobiontic microbial biofilms by scanning electron microscopy". Micron. 40 (3): 350–358. doi:10.1016/j.micron.2008.10.005. PMID 19027306.

- United Nations Ocean Economics and Technology Office, Technology Branch, United Nations (1978). Manganese Nodules: Dimensions and Perspectives. Marine Geology. Vol. 41. Springer. p. 343. Bibcode:1981MGeol..41..343C. doi:10.1016/0025-3227(81)90092-X. ISBN 978-90-277-0500-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Manganese Mining in South Africa – Overview". MBendi.com. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Elliott, R; Coley, K; Mostaghel, S; Barati, M (2018). "Review of Manganese Processing for Production of TRIP/TWIP Steels, Part 1: Current Practice and Processing Fundamentals". JOM. 70 (5): 680–690. Bibcode:2018JOM....70e.680E. doi:10.1007/s11837-018-2769-4. S2CID 139950857.

- Corathers, L. A.; Machamer, J. F. (2006). "Manganese". Industrial Minerals & Rocks: Commodities, Markets, and Uses (7th ed.). SME. pp. 631–636. ISBN 978-0-87335-233-8.

- Zhang, Wensheng; Cheng, Chu Yong (2007). "Manganese metallurgy review. Part I: Leaching of ores/secondary materials and recovery of electrolytic/chemical manganese dioxide". Hydrometallurgy. 89 (3–4): 137–159. doi:10.1016/j.hydromet.2007.08.010.

- Chow, Norman; Nacu, Anca; Warkentin, Doug; Aksenov, Igor & Teh, Hoe (2010). "The Recovery of Manganese from low grade resources: bench scale metallurgical test program completed" (PDF). Kemetco Research Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2012.

- "The CIA secret on the ocean floor". BBC News. 19 February 2018. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- "Project Azorian: The CIA's Declassified History of the Glomar Explorer". National Security Archive at George Washington University. 12 February 2010. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- Hein, James R. (January 2016). Encyclopedia of Marine Geosciences - Manganese Nodules. Springer. pp. 408–412. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Hoseinpour, Vahid; Ghaemi, Nasser (1 December 2018). "Green synthesis of manganese nanoparticles: Applications and future perspective–A review". Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology. 189: 234–243. doi:10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.10.022. PMID 30412855. S2CID 53248245. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- International Seabed Authority. "Polymetallic Nodules" (PDF). isa.org. International Seabed Authority. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Oebius, Horst U; Becker, Hermann J; Rolinski, Susanne; Jankowski, Jacek A (January 2001). "Parametrization and evaluation of marine environmental impacts produced by deep-sea manganese nodule mining". Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography. 48 (17–18): 3453–3467. Bibcode:2001DSRII..48.3453O. doi:10.1016/s0967-0645(01)00052-2. ISSN 0967-0645.

- Thompson, Kirsten F.; Miller, Kathryn A.; Currie, Duncan; Johnston, Paul; Santillo, David (2018). "Seabed Mining and Approaches to Governance of the Deep Seabed". Frontiers in Marine Science. 5. doi:10.3389/fmars.2018.00480. S2CID 54465407.

- Emsley 2001, pp. 422–425

- Dixon, P.; Curtis, David B.; Musgrave, John; Roensch, Fred; Roach, Jeff; Rokop, Don (1997). "Analysis of Naturally Produced Technetium and Plutonium in Geologic Materials". Analytical Chemistry. 69 (9): 1692–1699. doi:10.1021/ac961159q. PMID 21639292.

- Curtis, D.; Fabryka-Martin, June; Dixon, Paul; Cramer, Jan (1999). "Nature's uncommon elements: plutonium and technetium". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 63 (2): 275. Bibcode:1999GeCoA..63..275C. doi:10.1016/S0016-7037(98)00282-8.

- Hammond 2004, p. 4-1.

- Moore, C. E. (1951). "Technetium in the Sun". Science. 114 (2951): 59–61. Bibcode:1951Sci...114...59M. doi:10.1126/science.114.2951.59. PMID 17782983.

- Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- Emsley 2001, pp. 358–360.

- Rouschias, George (1974). "Recent advances in the chemistry of rhenium". Chemical Reviews. 74 (5): 531. doi:10.1021/cr60291a002.

- Anderson, Steve T. "2005 Minerals Yearbook: Chile" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- Korzhinsky, M. A.; Tkachenko, S. I.; Shmulovich, K. I.; Taran Y. A.; Steinberg, G. S. (2004-05-05). "Discovery of a pure rhenium mineral at Kudriavy volcano". Nature. 369 (6475): 51–52. Bibcode:1994Natur.369...51K. doi:10.1038/369051a0. S2CID 4344624.

- Kremenetsky, A. A.; Chaplygin, I. V. (2010). "Concentration of rhenium and other rare metals in gases of the Kudryavy Volcano (Iturup Island, Kurile Islands)". Doklady Earth Sciences. 430 (1): 114. Bibcode:2010DokES.430..114K. doi:10.1134/S1028334X10010253. S2CID 140632604.

- Tessalina, S.; Yudovskaya, M.; Chaplygin, I.; Birck, J.; Capmas, F. (2008). "Sources of unique rhenium enrichment in fumaroles and sulphides at Kudryavy volcano". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 72 (3): 889. Bibcode:2008GeCoA..72..889T. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2007.11.015.

- "The Mineral Rheniite". Amethyst Galleries.

- John, D. A.; Taylor, R. D. (2016). "Chapter 7: By-Products of Porphyry Copper and Molybdenum Deposits". In Philip L. Verplanck and Murray W. Hitzman (ed.). Rare earth and critical elements in ore deposits. Vol. 18. pp. 137–164.

- Magyar, Michael J. (January 2012). "Rhenium" (PDF). Mineral Commodity Summaries. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2013-09-04.

- "MinorMetal prices". minormetals.com. Retrieved 2008-02-17.

- Harvey, Jan (2008-07-10). "Analysis: Super hot metal rhenium may reach "platinum prices"". Reuters India. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- Glemser, O. (1963) "Ammonium Perrhenate" in Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry, 2nd ed., G. Brauer (ed.), Academic Press, NY., Vol. 1, pp. 1476–85.

- Rudenko, A.A.; Troshkina, I.D.; Danileyko, V.V.; Barabanov, O.S.; Vatsura, F.Y. (2021). "Prospects for selective-and-advanced recovery of rhenium from pregnant solutions of in-situ leaching of uranium ores at Dobrovolnoye deposit". Gornye Nauki I Tekhnologii = Mining Science and Technology (Russia). 6 (3): 158–169. doi:10.17073/2500-0632-2021-3-158-169. S2CID 241476783.

- Hawecker, Jeannot (1984). "Electrocatalytic Reduction of Carbon Dioxide Mediated by Re(bipy)(CO)3Cl (bipy = 2,2'-bipyridine)". J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun.: 328–330. doi:10.1039/C39840000328.

- Sullivan, B. Patrick (1985). "One- and Two-electron Pathways in the Electrocatalytic Reduction of CO2 by fac-Re(bpy)(CO)3Cl (bpy = 2,2'-bipyridine)". J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun.: 1414–1416. doi:10.1039/C39850001414.

- Grice, Kyle (2014). "Recent Studies of Rhenium and Manganese Bipyridine Carbonyl Catalysts for the Electrochemical Reduction of CO2". Advances in Inorganic Chemistry. 66: 163–188. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-420221-4.00005-6. ISBN 9780124202214.

- Francke, Robert (2018). "Homogeneously Catalyzed Electroreduction of Carbon Dioxide -- Methods, Mechanisms, and Catalysts". Chemical Reviews. 118 (9): 4631–4701. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00459. PMID 29319300.

- Bourrez, Marc (2011). "[Mn(bipyridyl)(CO)3Br]: an abundant metal carbonyl complex as efficient electrocatalyst for CO2 reduction". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 50 (42): 9903–9906. doi:10.1002/anie.201103616. PMID 21922614.

- Laurence Knight (30 May 2015). "The element that can make bones glow". BBC. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- Guérin B; Tremblay S; Rodrigue S; Rousseau JA; et al. (2010). "Cyclotron production of 99mTc: an approach to the medical isotope crisis" (PDF). Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 51 (4): 13N–6N. PMID 20351346.

- Rimshaw, S. J. (1968). Hampel, C. A. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of the Chemical Elements. New York: Reinhold Book Corporation. pp. 689–693.

- Schwochau 2000, p. 414.

- Alberto, Roger; Nadeem, Qaisar (2021). "Chapter 7. 99m Technetium-Based Imaging Agents and Developments in 99Tc Chemistry". Metal Ions in Bio-Imaging Techniques. Springer. pp. 195–238. doi:10.1515/9783110685701-013. S2CID 233684677.

- Schwochau 2000, pp. 12–27.

- Schwochau 2000, p. 87.

- James S. Tulenko; Dean Schoenfeld; David Hintenlang; Carl Crane; Shannon Ridgeway; Jose Santiago; Charles Scheer (2006-11-30). University Research Program in Robotics REPORT (PDF) (Report). University of Florida. doi:10.2172/895620. Retrieved 2007-10-12.

- Schwochau 2000, pp. 87–90.

- Emsley 2001, p. 425.

- "Ch. 14 Separation Techniques" (PDF). EPA: 402-b-04-001b-14-final. US Environmental Protection Agency. July 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-03-08. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- Schwochau 2000, p. 91.

Bibliography

- Hammond, C. R. (2004). Lide, David R. (ed.). CRC handbook of chemistry and physics : a ready-reference book of chemical and physical data. Boca Raton : CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-0485-9.

- Schwochau, K. (2000). Technetium: Chemistry and Radiopharmaceutical Applications. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-29496-1.