Massacres of Azerbaijanis in Armenia (1917–1921)

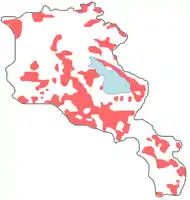

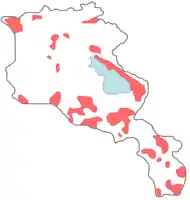

In the aftermath of World War I and during the Armenian–Azerbaijani and Russian Civil wars, there were mutual massacres committed by Armenians and Azerbaijanis against each other. While a significant portion of the Muslim population (Mostly Tatars[lower-alpha 1]) of the Erivan Governorate were displaced during the internecine conflict due to the actions of Armenian irregulars and militias, the government of Armenia pursued a policy of ethnic homogenisation in affected areas. Starting in 1918, Armenian partisans expelled and massacred thousands of Azerbaijani Muslims in Zangezur and destroyed their settlements in an effort to "re-Armenianize" the region. These actions were cited by Azerbaijan as a reason to start a military campaign in Zangezur. Ultimately, Azerbaijan took in and resettled tens of thousands of Muslim refugees from Armenia. The total number of killed is a matter of scholarly dispute. By the outset of Armenia's independence, the country's Turkic population was more than 10 thousand.

Background

Following the Russian annexation of Iranian Armenia, tens of thousands of Armenians repatriated to Russian Armenia in 1828–1831, thereby regaining an ethnic majority in their homeland for the first time in "several hundred years".[3] Despite this, the Russian Empire census indicated there to be over 240 thousand Muslims on the territory of present-day Armenia in 1897, indicated by previous censuses to be mostly Tatars[lower-alpha 1] (forming over 30 percent of the population).[4] As a result of rising nationalism in the South Caucasus, ethnic clashes erupted between Armenians and Tatars in the Russian Empire between 1905 and 1907, resulting in massacres of thousands[5] and the destruction of 128 and 158 Armenian and Tatar villages, respectively.[6]

Until the Ottoman invasion of the South Caucasus in 1918, Armenians and Tatars lived "relatively peacefully" throughout the First World War.[7] Tensions rose after both Armenia and Azerbaijan became briefly independent from Russia in 1918 as both quarrelled over where their common borders lay.[8][9]

Events

Expert on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict Thomas de Waal wrote that Azerbaijanis in Armenia became the "collateral victims" of the Armenian genocide carried out by the Ottoman Empire years prior; also adding that despite Azerbaijanis being represented by three delegates in an eighty-seat Armenian parliament, they were universally targeted as "Turkish fifth columnists".[10] In the aftermath of World War I, and during the Armenian–Azerbaijani war and Russian Civil War, there were mutual massacres committed by Armenians and Azerbaijanis against each other.[9] The Erivan Governorate, which formed a part of the Armenian republic,[11] had a "significant Muslim population until 1919".[12]

In April 1920, British journalist C. E. Bechhofer Roberts described the state of Armenia: "You cannot persuade a party of frenzied nationalists that two blacks do not make a white; consequently, no day went by without a catalogue of complaints from both sides, Armenian and Tartar, of unprovoked attacks, murders, village burnings and the like. Superficially, the situation was a series of vicious circles. Tartar and Armenian attacked and retaliated for attacks. Fear drove on each side to fresh excesses."[13]

In the Erivan Governorate and Kars Oblast

Mustafa Kemal, the leader of the Turkish National Movement, in justifying an invasion of Armenia, stated that reportedly nearly 200 villages were burned by Armenians and most of their 135 thousand inhabitants were "eliminated".[14] Historian Richard Hovannisian wrote that nearly a third of the 350 thousand Muslims of the Erivan Governorate were displaced from their villages in 1918–1919 and living in the outskirts of Yerevan or along the former Russo-Turkish border in emptied Armenian homes. In 1919, the Armenian government declared the right of return of all refugees, however, this was unimplemented in emptied Muslim settlements occupied by Armenian refugees.[15] During his tenure as minister of war, Rouben Ter Minassian transferred many of the 30 thousand Armenian refugees from Zangezur to replace evicted Muslims and homogenise certain areas,[16] such regions included Erivan (present-day Ararat) and Daralayaz.[17] Ter Minassian, displeased with the fact that Azerbaijanis in Armenia lived on fertile lands, waged at least three campaigns aimed at cleansing Azerbaijanis from 20 villages outside Erivan, as well as in the south of the country. According to French historian (and Ter Minassian's daughter-in-law) Anahide Ter Minassian, to achieve his goals, he used intimidation and negotiations, but above all, "fire and steel" and "the most violent methods to 'encourage' Muslims in Armenia" to leave.[10] Historian Benjamin Lieberman wrote: "For some 20 miles (32 kilometres) along Lake Sevan … deserted houses lay 'in ruins from internecine conflicts between Armenians and Tatars.'"[18]

In October 1919, Muslim authorities in Kars appealed to Azerbaijan for means to transport 25 thousand refugees.[19]

In Zangezur

Throughout 1918–1921, Armenian commanders Andranik Ozanian[20][21][22][23][24][25][26] and Garegin Nzhdeh brought about a "re-Armenianization" of Zangezur[27][28][29][30][31] through the expulsion of tens of thousands[32] (40[33]–50 thousand[34][35]) and the massacre of 10 thousand Azerbaijanis.[36] A message dated 12 September from the local county chief indicated that the villages of Rut, Darabas, Agadu, Vagudu were destroyed, and Arikly, Shukyur, Melikly, Pulkend, Shaki, Kiziljig, the Muslim part of Karakilisa, Irlik, Pakhlilu, Darabas, Kyurtlyar, Khotanan, Sisian, and Zabazdur were set aflame, resulting in the deaths of 500 men, women, and children.[37] In the Barkushat–Geghvadzor valleys and southeast of Goris, nine villages and forty hamlets were "wiped out" in January 1920 in an act of retribution for the massacre of Armenians in Agulis.[38]

The number of Muslim settlements in Zangezur destroyed by Andranik and Nzhdeh is given by different authors as 24,[33] 49 (9 villages and 40 hamlets),[38] or 115.[34][35] The destruction of these settlements and the restriction imposed by local Armenians on Muslim shepherds taking their flocks into Zangezur was cited by Azerbaijan as the reason for their military campaign against Zangezur in late-1919.[33] During the 1921 anti-Soviet revolt established as the Republic of Mountainous Armenia, Nzhdeh, in taking control of Zangezur, drove "out the last of its Azerbaijani population".[28] According to Mark Levene, 250 Muslim villages had been burnt in the eastern Caucasus by May 1918—as a result of a killing spree initiated by Armenian units led by Andranik.[39]

Casualties and displaced persons

| Region | Settlements destroyed | Population displaced | Population massacred |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erivan Governorate | 135,000[40] | ||

| ↳ Surmalu uezd | 24[41]–38[42] | 40,000[42] | |

| Kars oblast | 10,000[43] | ||

| Zangezur uezd | 49[38]–115[35] | 40,000[33]–50,000[35] | 10,000[36] |

| TOTAL | 73–153 | 225,000–235,000 | 10,000 |

Aftermath

In April 1920, the archbishop of Yerevan, Khoren I of Armenia, admitted that "a few Tatar villages under the Armenian Government have suffered" while also justifying it by stating that "they were the aggressors, either they actually attacked us, or they were being organised by the Azerbaijan agents and official representatives to rise against the Armenian Government."[44]

Changes in ethnic composition

By time of Armenia's sovietisation, "more than 10 thousand Turks" remained within the borders of Armenia.[45] By the time of 1922 agricultural census, some 60 thousand Azerbaijani refugees had been repatriated, thereby bringing their total up to 72,596.[45] Muslims numbered 240,323 (30.1 percent of the population) in 1897,[4] by 1922, Turko-Tatars[lower-alpha 1] numbered 77,767 (9.9 percent of the population).[46]

Zangezur census data

According to the Russian Empire census for the year 1897, the territory of Armenian-controlled Zangezur was 68 percent (59,207) Armenian and 31 percent (27,031) Muslim with a total population of 87,252.[4] According to the Armenian agricultural census of 1922, the first census after the brief independence of Armenia, it was revealed that Zangezur's population had declined to 75,994, 89 percent (67,587) of whom were Armenians and 11 percent (8,224) were Azerbaijanis.[46] Thus, the Armenian population had increased by 14 percent whilst the Azerbaijani Muslim population decreased by 70 percent.

| Nationality | 1897[4] | 1922[46] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | |

| Armenians | 59,207 | 67.9 | 67,587 | 88.9 |

| Muslims[lower-alpha 2] | 27,031 | 31.0 | 8,224 | 10.8 |

| Others | 1,014 | 1.2 | 183 | 0.2 |

| TOTAL | 87,252 | 100.0 | 75,994 | 100.0 |

Azerbaijani Government's reaction

To assist the destitute 70–80 thousand Muslim refugees living south of Yerevan (50 thousand of whom were dependent on relief aid during the winter), the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic transferred large amounts of funds. It was reported in 1919–1920 that there were 13 thousand Muslims in Yerevan and another 50 thousand throughout Armenia. Muslims, in contrast with their coreligionists in the south of the country lived "acceptably" and with "generally cordial" interethnic relations in the north. The 40 thousand Muslims who had fled from Armenia to Azerbaijan were resettled through a 69 million ruble allocation by the Azerbaijani government.[19]

Contemporary assessment

Turkish-German historian Taner Akçam criticized Turkish efforts to equate these events with the previous Armenian genocide. He also criticzed the death figures in primary sources for often being "freely invented by the authors" and exaggerations of "destroyed villages" referring to settlements of 4–5 inhabitants.[47] Besides this, Akçam also criticizes accounts under which the Muslim deaths are just further revenge killings typical of the period:

There is no doubt that the events in Caucasus [between 1917 and 1922] were part of a historical continuity in the region. However, while there is continuity of the actors, there are significant changes to the context in which these events took place. The decline of empires and rise of new nation-states changed the nature of the events in very important ways that negate a description of Muslim deaths during this period as simply "acts of revenge." The newly formed Armenian state was itself attempting to establish an ethnically homogenous nation.[47]

See also

Notes

- Prior to 1918, Azerbaijanis were generally known as "Tatars". This term, employed by the Russians, referred to Turkic-speaking Muslims of the South Caucasus. After 1918 with the establishment of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, and "especially during the Soviet era", the Tatar group identified itself as "Azerbaijani".[1][2]

- The 1922 agricultural census enumerated the number of "Turko-Tatars".

References

- Bournoutian 2018, p. 35 (note 25).

- Tsutsiev 2014, p. 50.

- Herzig & Kurkchiyan 2005, p. 66.

- Korkotyan 1932, pp. 164–165.

- Hovannisian 1967, p. 264.

- Akouni 2011, p. 30.

- Wright 2003, p. 98.

- de Waal 2003, pp. 127–128.

- Kaufman 2001, p. 58.

- de Waal 2015, p. 75.

- Herzig & Kurkchiyan 2005, p. 110.

- Bournoutian 2015, p. 33.

- de Waal 2003, pp. 143.

- Hovannisian 1996b, p. 247.

- Hovannisian 1982, p. 178.

- Bloxham 2005, p. 103.

- Leupold 2020, p. 25.

- Lieberman 2013, p. 136.

- Hovannisian 1982, p. 182.

- de Waal 2003, pp. 127–129.

- Arslanian 1980, p. 93.

- Namig 2015, p. 240.

- Gerwarth & Horne 2012, p. 179.

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 87.

- Hovannisian 1982, p. 207.

- Leupold 2020, p. 24.

- Broers 2019, p. 4.

- de Waal 2003, p. 129.

- Chorbajian 1994, p. 134.

- Zakharov 2017, pp. 105–106.

- Ovsepyan 2001, p. 224.

- de Waal 2003, p. 80.

- Hovannisian 1982, p. 213.

- Mammadov & Musayev 2008, p. 33.

- Balayev 1990, p. 43.

- Coyle 2021, p. 49.

- Buldakov 2010, pp. 893–894.

- Hovannisian 1982, p. 239.

- Levene 2013, p. 217.

- Hovannisian 1996b, p. 147.

- Hovannisian 1982, p. 106.

- Chmaïvsky 1919, p. 8.

- Hovannisian 1996a, p. 122.

- Bloxham 2005, p. 105.

- Korkotyan 1932, p. 184.

- Korkotyan 1932, p. 167.

- Akçam 2007, p. 330.

Bibliography

- Akçam, Taner (2007). A Shameful Act: The Armenian Genocide and the Question of Turkish Responsibility. New York: Metropolitan Books. ISBN 978-0805079326.

- Akouni, E. (2011). Political Persecution: Armenian Prisoners Of The Caucasus (a Page Of The Tzar's Persecution). Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1179951164.

- Arslanian, Artin H. (1980). "Britain and the question of Mountainous Karabagh". Middle Eastern Studies. 16 (1): 92–104. doi:10.1080/00263208008700426. ISSN 0026-3206.

- Balayev, Aydyn (1990). Азербайджанское национально-демократическое движение 1917-1929 гг [The Azerbaijani national-democratic movement in 1917–1929] (in Russian). Baku. ISBN 978-5-8066-0422-5. Archived from the original on 7 November 2022.

- Bloxham, Donald (2005). The Great Game of Genocide: Imperialism, Nationalism, and the Destruction of the Ottoman Armenians. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-927356-1. OCLC 57483924.

- Bournoutian, George (2015). "Demographic Changes in the Southwest Caucasus, 1604–1830: The Case of Historical Eastern Armenia". Forum of EthnoGeoPolitics. Amsterdam. 3 (2). ISSN 2352-3654.

- Bournoutian, George A. (2018). Armenia and Imperial Decline: The Yerevan Province, 1900–1914. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-06260-2. OCLC 1037283914.

- Broers, Laurence (2019). Armenia and Azerbaijan: Anatomy of a Rivalry. Edinburgh, UK. ISBN 978-1-4744-5054-6. OCLC 1127546732.

- Buldakov, V. P. (2010). Хаос и этнос. Этнические конфликты в России, 1917-1918 гг [Chaos and ethnicity: Ethnic conflicts in Russia, 1917–1918] (in Russian). Moscow: Novy khronograf. ISBN 978-5-94881-160-4. OCLC 765812131.

- Chmaïvsky, Imprimerie H. (1919). L'Etat du Sud-Ouest du Caucase [Southwestern Caucasus State] (in French). Batoum: le Comité central pour la défense des intérêts de la population du Sud-Ouest. Archived from the original on 16 November 2022. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- Chorbajian, Levon (1994). The Caucasian Knot: The History & Geopolitics of Nagorno-Karabagh. Patrick Donabédian, Claude Mutafian. London: Atlantic Highlands, NJ. ISBN 1-85649-287-7. OCLC 31970952.

- Coyle, James J. (2021). Russia's Interventions in Ethnic Conflicts: The Case of Armenia and Azerbaijan. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-59573-9. ISBN 978-3-030-59572-2. S2CID 229424716.

- de Waal, Thomas (2003). Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0814719459.

- de Waal, Thomas (2015). Great Catastrophe: Armenians and Turks in the Shadow of Genocide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-935070-4. OCLC 897378977.

- Gerwarth, Robert; Horne, John, eds. (2012). War in Peace: Paramilitary Violence in Europe after the Great War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191626531. OCLC 827777835.

- Herzig, Edmund; Kurkchiyan, Marina (2005). The Armenians: Past and Present in the Making of National Identity. London: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-203-00493-0. OCLC 229988654.

- Hovannisian, Richard G (1967). Armenia on the Road to Independence, 1918. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520005747. OCLC 1028172352.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1971). The Republic of Armenia: The First Year, 1918–1919. Vol. 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520019843.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1982). The Republic of Armenia: From Versailles to London, 1919–1920. Vol. 2. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520041868.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1996a). The Republic of Armenia: From London to Sèvres, February–August 1920. Vol. 3. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520088030.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1996b). The Republic of Armenia: Between Crescent and Sickle: Partition and Sovietization. Vol. 4. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520088047.

- Kaufman, Stuart J. (2001). Modern Hatreds: The Symbolic Politics of Ethnic War. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8736-1.

- Kazemzadeh, Firuz (1951). The Struggle for Transcaucasia (1917–1921). New York City: Philosophical Library. ISBN 978-0-95-600040-8.

- Korkotyan, Zaven (1932). Խորհրդային Հայաստանի բնակչությունը վերջին հարյուրամյակում (1831-1931) [The population of Soviet Armenia in the last century (1831–1931)] (PDF) (in Armenian). Yerevan: Pethrat. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2022.

- "Les musulmans en Arménie". Le Temps. 25 July 1920.

- Leupold, David (2020). Embattled Dreamlands: the Politics of Contesting Armenian, Kurdish and Turkish Memory. New York. ISBN 978-0-429-34415-2. OCLC 1130319782.

- Levene, Mark (2013). Devastation: The European Rimlands 1912–1938. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191505546.

- Lieberman, Benjamin (2013). Terrible Fate: Ethnic Cleansing in the Making of Modern Europe. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4422-3038-5. OCLC 866448976.

- Mammadov, Ilgar; Musayev, Tofik (2008). Армяно-азербайджанский конфликт: История, Право, Посредничество [Armenian–Azerbaijani conflict: history, law, mediation] (in Russian) (2nd ed.). Baku: Graf and K Publishing House. ISBN 9785812509354.

- Namig, Sadiqova Sayyara (2015). "Unforgettable Azerbaijani painter Huseyn Aliyev". Problemy Sovremennoy Nauki I Obrazovaniya. 12 (42). ISSN 2304-2338.

- Ovsepyan, Vache (2001). Гарегин Нжде и КГБ [Garegin Nzhdeh and the KGB] (in Russian). Yerevan. Archived from the original on 30 October 2007.

- Tarasov, Stanislav (7 July 2014). "Зачем Азербайджану Новая "Историческая Родина"" [Why does Azerbaijan need a new 'historical homeland']. iarex.ru. Archived from the original on 14 October 2022.

- Tsutsiev, Arthur (2014). Atlas of the Ethno-Political History of the Caucasus. Translated by Nora Seligman Favorov. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300153088.

- Volkova, Nataliya G. (1969). Gardanov, V. K. (ed.). Кавказский этнографический сборник [Caucasian ethnographical collection] (PDF) (in Russian). Vol. 4. Moscow: Nauka. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 July 2022.

- Wright, John (2003). Transcaucasian Boundaries. New York: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0805079326.

- творчество (Фольклор), Народное (2018). Andranik. Armenian Hero. New York: ЛитРес. ISBN 9785040624676.

- Zakharov, Nikolay (2017). Law, Ian (ed.). Post-Soviet Racisms. Leeds, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-47692-0. OCLC 976083039.