Republican People's Party

The Republican People's Party (Turkish: Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi, pronounced [dʒumhuːɾiˈjet haɫk 'paɾtisi] (![]() listen), acronymized as CHP [dʒeːheːpeˑ]) is a Kemalist and social democratic political party in Turkey.[5] It is the oldest political party in Turkey, founded by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the first president and founder of the modern Turkish Republic. The party is also cited as the founding party of modern Turkey.[6] Its logo consists of the Six Arrows, which represent the foundational principles of Kemalism: republicanism, reformism, laicism (Laïcité/Secularism), populism, nationalism, and statism. It is currently the second largest party in Grand National Assembly with 135 MPs, behind the ruling conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP).

listen), acronymized as CHP [dʒeːheːpeˑ]) is a Kemalist and social democratic political party in Turkey.[5] It is the oldest political party in Turkey, founded by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the first president and founder of the modern Turkish Republic. The party is also cited as the founding party of modern Turkey.[6] Its logo consists of the Six Arrows, which represent the foundational principles of Kemalism: republicanism, reformism, laicism (Laïcité/Secularism), populism, nationalism, and statism. It is currently the second largest party in Grand National Assembly with 135 MPs, behind the ruling conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP).

The political party has its origins in the various resistance groups founded during the Turkish War of Independence. Under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk they united in the 1919 Sivas Congress. In 1923, the "People's Party", soon adding the word "Republican" to its name, declared itself to be a political organisation and announced the establishment of the Turkish Republic, with Atatürk as its first president. As Turkey moved into its authoritarian one-party period, the CHP was the apparatus of implementing far reaching political, cultural, social, and economic reforms in the country.

After World War II, Atatürk's successor, İsmet İnönü, allowed for multi-party elections, and the party initiated a peaceful transition of power after losing the 1950 election, ending the one-party period and beginning Turkey's multi-party period. The years following the 1960 military coup saw the party gradually trend towards the center-left, which was cemented once Bülent Ecevit became chairman in 1972. The CHP, along with all other political parties of the time, was banned by the military junta of 1980. The CHP was re-established with its original name by Deniz Baykal on 9 September 1992, with the participation of a majority of its members from the pre-1980 period. Since 2002 it has been the main opposition party to the ruling AKP.[7] In 2010 Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu became chairman of the CHP.

It is a founding party of the Nation Alliance, a diverse coalition of opposition parties against the AKP and their People's Alliance. In addition, CHP is an associate member of the Party of European Socialists (PES), a member of the Socialist International, and the Progressive Alliance. Many politicians of CHP have declared their support for LGBT rights and the feminist movement in Turkey. The party is pro-European and supports Turkish membership to European Union and NATO.

History

Establishment: 1919–1923

The Republican People's Party has its origins in the resistance organizations, known as Defence of Rights Associations, created in the immediate aftermath of World War I in the Turkish War of Independence. In the Sivas Congress, Mustafa Kemal Pasha (Atatürk) and his colleagues united the Defence of Rights Associations into the Association for the Defence of National Rights of Anatolia and Rumelia (Anadolu ve Rumeli Müdâfaa-i Hukuk Cemiyeti) (A-RMHC), and called for elections in the Ottoman Empire to elect representatives associated with the organization. Most members of the A-RMHC were previously associated with the Committee of Union and Progress.[8]

A-RMHC members proclaimed the Grand National Assembly as a counter government from the Ottoman government in Istanbul. Grand National Assembly forces militarily defeated Greece, France, and Armenia, overthrew the Ottoman government, and abolished the monarchy. After the 1923 election, A-RMHC was transformed into a political party called the People's Party (Halk Fırkası). Because of the unanimity of the new parliament, the republic was proclaimed, the Treaty of Lausanne was ratified, and the Caliphate was abolished the next year.[9]

One-party period: 1923–1950

Atatürk era

In 1924, opposition to Mustafa Kemal Atatürk resulted in the foundation of the Progressive Republican Party (TCF). Reacting to the foundation of the TCF, his People's Party changed its name to the Republican People's Party (Cumhuriyet Halk Fırkası, soon Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi) (CHP). The life of the TCF was short. The TCF faced allegations of involvement in the Sheikh Said rebellion and for conspiring with remaining members of the CUP to assassinate Atatürk in the İzmir Affair. Because of this the party was banned, and its members purged from the government. For the next two decades Turkey was under a one-party authoritarian regime, with one interruption; another brief experiment of opposition politics through the formation of the Liberal Republican Party.

From 1924–1946, the CHP introduced sweeping social, cultural, educational, economic, and legal reforms that transformed Turkey into a Western modeled state. Such reforms included the adoption of Swiss and Italian legal and penal codes, the acceleration of industrialization, land reform and rural development programs, forced assimilation policies, strict secularism, women's suffrage, and switching written Turkish from Arabic script into Latin script, to name a few. In the period of 1930–1939, Atatürk's CHP clarified its ideology by adopting the 'Six Arrows': republicanism, reformism, laïcité, populism, nationalism, and statism, as well as borrowing tenets from Communism and (Italian) Fascism.[10]

Opposition to Atatürk's reforms were suppressed by various coercive institutions and military force, at the expense of religious conservatives, Kurds, and communists. In the party's third convention, it clarified its approach towards the religious minorities of the Christians and the Jews, accepting them as real Turks as long as they adhere to the national ideal and use the Turkish language.[11] Under the state sanctioned secularist climate Alevis were able to make great strides in their emancipation, and to this day make up a core constituency of the CHP. With the onset of the Great Depression, the party divided into statist and liberal factions, being championed by Atatürk's prime minister İsmet İnönü and his finance minister Celal Bayar respectively. Atatürk mostly favored İnönü's policies, so economic development of the early republic was largely confined to state-owned enterprises and five-year plans.

İnönü era

On 12 November 1938, the day after Atatürk's death, his ally İsmet İnönü was elected the second president and assumed leadership of the Republican People's Party.[12] İnönü's presidency saw heavy state involvement in the economy and further rural development initiatives such as Village Institutes. On foreign affairs, the Hatay State was annexed and İnönü adopted a policy of neutrality despite attempts by the Allies and Axis powers to bring Turkey into World War II, during which extensive conscription was implemented to ensure an armed neutrality. Non-Muslims especially suffered when the CHP government implemented discriminatory "wealth taxes," labor battalions, and peon camps. Over the course of the war, the CHP eventually rejected pan-Turkism, with Turanists being purged in the Racism-Turanism Trials.

In the aftermath of World War II, İnönü called for a multi-party general election in 1946 – the first multi-party general election in the country's history. The Motion with Four Signatures resulted in the resignation of some CHP members including Bayar, who then founded the Democrat Party (DP), which challenged the party in the election. The result was a victory for the CHP, which won 395 of the 465 seats, amid criticism that the election did not live up to democratic standards. Under pressure by the new conservative parliamentary opposition and the United States, the party became especially anti-communist, and retracted some of its rural development programs and anti-clerical policies.[13][14][15]

The period between 1946 and 1950 saw İnönü prepare for a pluralistic Turkey as he abolished his title of "unchangeable chairman" of the CHP.[16][17] Four years later, a more free and fair general election was held in 1950 that led to the CHP losing power to the DP. İnönü presided over a peaceful transition of power. The 1950 election marked the end of the CHP's last majority government. The party has not been able to regain a parliamentary majority in any subsequent election since.[18]

Road to the center-left: 1950–1980

Due to the winner-take-all system in place during the 1950s, the DP achieved landslide victories in elections that were reasonably close, meaning the CHP was in opposition for 10 years. In the mean time, the party began a long transformation into a social democratic force. Even before losing power İnönü created the ministry of labor and signed workers protections into law, and universities were given autonomy from the state.[16] In its ninth congress in 1951, the youth branch and the women's branch were founded. In 1953, the establishment of trade unions and vocational chambers was proposed, and the right to strike for workers was added to the party program.[19]

Despite its name, the Democrat Party became increasingly authoritarian by the end of its rule. İnönü was harassed and almost lynched multiple times by DP supporters, and the DP government confiscated CHP property and harassed their members. The DP blocked the CHP from forming an electoral alliance with opposition parties for the 1957 snap election. By 1960, the DP accused the CHP of plotting a rebellion and threatened its closure. With the army concerned by the DP's authoritarianism, Turkey's first military coup was performed by junior officers. After one year of junta rule the DP was banned and Prime Minister Adnan Menderes and a couple of his ministers were tried and executed. Right-wing parties which trace their roots to the DP have since continuously attacked the CHP for their perceived involvement in the hanging of Menderes.[20]

The CHP emerged as the first-placed party at the general election of 1961, and formed a grand coalition with the Justice Party, a successor-party to the Democrat Party. This was the first coalition government in Turkey, which endured for seven-months. İnönü was able to form two more governments with other parties until the 1965 election. His labor minister Bülent Ecevit was instrumental in giving Turkish workers the right to strike and collective bargaining. As leader of the Democratic Left movement in the CHP, Ecevit contributed to the party adopting the Left of Centre (Ortanın solu) programme for that election, which they lost against the Justice Party.[21]

İnönü favored Ecevit's controversial faction, resulting in Turhan Feyzioğlu leaving and founding the Reliance Party. When asked about his reasoning for his favoring Ecevit, İnönü replied: "Actually we are already a left-to-center party after embracing Laïcité. If you are populist, you are (also) at the left of center."[22] İnönü remained as opposition leader and the leader of the CHP until 8 May 1972, when he was overthrown by Ecevit in a party congress, due to his endorsement of the military intervention of 1971.

Ecevit adopted a distinct left wing role in politics and, although remaining staunchly nationalist, attempted to implement democratic socialism into the ideology of CHP. Support for the party increased when he became prime minister in 1973 and invaded Cyprus. The 1970s saw the party solidify its relations with trade unions and leftist groups in an atmosphere of intense polarization and political violence. The CHP achieved its best ever result in a free and fair multi-party election under Ecevit, when in 1977, the party received 41% of the vote. Ecevit and his political rival Süleyman Demirel would constantly turnover the premiership as partisan deadlock took hold. This ended in a military coup in 1980, resulting in the banning of every political party and major politicians being jailed and banned from politics.[23]

Recovery period: 1980–2002

Both the party name "Republican People's Party" and the abbreviation "CHP" were banned until 1987. Until 1999, Turkey was ruled by the centre-right Motherland Party (ANAP) and the True Path Party (DYP), unofficial successors of the Democrat Party and the Justice Party, as well as, briefly, by the Islamist Welfare Party. CHP supporters also established successor parties. By 1985, Erdal İnönü, İsmet İnönü's son, consolidated two successor parties to form the Social Democratic Populist Party (SHP), while the Democratic Left Party (Turkish: Demokratik Sol Parti, DSP) was formed by Rahşan Ecevit, Bülent Ecevit's wife (Bülent Ecevit took over the DSP in 1987).[24]

After the ban on pre-1980 politicians was lifted in 1987, Deniz Baykal, a household name from the pre-1980 CHP, reestablished the Republican People's Party in 1992, and the SHP merged with the party in 1995. However, Ecevit's DSP remained separate, and to this day has not merged with the CHP.[25] Observers noted that the two parties held similar ideologies and split the Kemalist vote in the nineties. The CHP held an uncompromisingly secularist and establishmentalist character and supported bans of headscarves in public spaces and the Kurdish language.[26]

From 1991 to 1996, the SHP and then the CHP were in coalition governments with the DYP. Baykal supported Mesut Yılmaz's coalition government after the collapse of the Welfare-DYP coalition following the 28 February "post-modern coup." However, due to the Türkbank scandal, the CHP withdrew its support and helped depose the government with a no confidence vote. Ecevit's DSP formed an interim-government, during which the PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan was captured in Kenya. As such, in the election of 1999, the DSP benefited massively in the polls at the expense of CHP, and the party failed to exceed the 10% threshold (8.7% vote), not winning any seats.

Main opposition under Baykal: 2002–2010

In the 2002 general election, the CHP came back with 20% of the vote but 32% of the seats in parliament, as only it and the new AKP (Justice and Development Party) received above the 10% threshold to enter parliament. With DSP's collapse, CHP became Turkey's main Kemalist party. It also became the second largest party and the main opposition party, a position it has retained since. Since the dramatic 2002 election, the CHP has been racked by internal power struggles, and has been outclassed by the AKP governments of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Many of its members were critical of the leadership of CHP, especially Baykal, who they complained was stifling the party of young blood by turning away the young who turn either to apathy or even vote for the AKP.

_edit.jpg.webp)

In 2007, the culmination of tensions between the secularist establishment and AKP politicians turned into a political crisis. The CHP assisted undemocratic attempts by the army and judiciary to shut down the newly elected party. The crisis began with massive protests by secularists supported by the CHP in reaction to the AKP's candidate for the that year's presidential election: Abdullah Gül, due to his background in Islamist politics and his wife's wearing of the hijab. The CHP chose to boycott the election.[27]

Without quorum, Erdoğan called for a snap election to increase his mandate, in which the CHP formed an electoral alliance with the declining DSP, but gained only 21% of the vote. During the campaign season, a memorandum directed at the AKP was posted online by the Turkish Armed Forces. The CHP continued to boycott Gül's second attempt to be voted president, though this time Gül had the necessary quorum with MHP's participation and won.[28] The swearing-in ceremony was boycotted by the CHP and the Chief of the General Staff Yaşar Büyükanıt.[29]

The party also voted against a package of constitutional amendments to have the president elected by the people instead of parliament, which was eventually put to a referendum. The "no" campaign, supported by the CHP, failed, as a majority of Turks voted in favor of direct presidential elections. The final challenge against the AKP's existence was a 2008 closure trial which ended without a ban. Following the decision, the AKP government, in a covert alliance with the Gülen movement, began a purge of the Turkish military, judiciary, and police forces of secularists in the Ergenekon and Sledgehammer trials, which the CHP condemned.[30] Between 2002 and 2010, Turkey held three general elections and two local elections, all of which the CHP received between 18-23% of the vote.

An extraordinary vote in parliament saw half of the AKP's parliamentary group vote with the CHP against joining the US-lead coalition invasion of Iraq.[31]

Main opposition under Kılıçdaroğlu: 2010–present

On 10 May 2010, Deniz Baykal announced his resignation as leader of the Republican People's Party after a sex tape of him was leaked to the media. Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu was elected to be the new party leader.[32] Kılıçdaroğlu has been returning the CHP to its traditional social-democratic image and casting away its secularist statist–establishmentalist character. This has involved building bridges to voters it has traditionally not attracted: the devout, Kurds, and right-wing voters.[33]

However even with Kılıçdaroğlu at the helm, after four general elections the CHP has still not won an election, receiving between only 22 and 26% of the vote in parliamentary elections. The CHP supported the unsuccessful "no" campaign in the 2010 constitutional referendum. In his first general election in 2011, the party increased its support by 25% but not enough to unseat the AKP. The 2013 Gezi Park protests found much support in the CHP.

The 2014 presidential election was the first in which the position would be directly elected and came just after a massive corruption scandal. The CHP and MHP's joint candidate Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu still lost to Erdoğa with only 38% of the vote. The two parties were critical of the government's negotiations for peace with the PKK, which lasted from 2013–July 2015. In the June 2015 general election, the AKP lost its parliamentary majority due to the debut of the pro-Kurdish People's Democratic Party (HDP), which was possible because of strategic voting by CHP voters so the party could pass the 10% threshold.[34]

Coalition talks went nowhere. The CHP refused to govern with the AKP after negotiations, while MHP ruled out partaking in a government with HDP. In a snap election held that November, the AKP regained their parliamentary majority as well as MHP's support. Kılıçdaroğlu supported the government in the 2016 coup d'etat attempt, the subsequent purges, and incursions into Syria.[34] This support went so far as to help the government pass a law to lift parliamentary immunities, resulting in the jailing of MPs from the HDP, including Selahattin Demirtaş, as well as CHP lawmakers.[35] The party lead the unsuccessful "no" campaign for the 2017 constitutional referendum.

.jpg.webp)

By 2017, dissidents from MHP founded the Good Party. Kılıçdaroğlu was instrumental in the facilitating the rise of the new party by transferring MPs so they would have a parliamentary group to compete in the 2018 election. In the 2018 general election the CHP, Good Party, Felicity, and Democrat Party established the Nation Alliance to challenge the AKP and MHP's People's Alliance.[36][37] Though CHP's vote was reduced to 22%, strategic voting for the other parties yielded the alliance 33% of the vote. Their candidate for president: Muharrem İnce, received only 30% of the vote. The Nation Alliance was re-established for the 2019 local elections, which saw great gains for the CHP, capturing nearly 30% of the electorate. A tacit collaboration with the HDP (which continues to today) allowed for CHP to win the municipal mayoralties of İstanbul and Ankara.[33]

Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu is CHP's and the Nation Alliance's candidate for the 2023 presidential election, with Ekrem İmamoğlu and Mansur Yavaş, mayors of İstanbul and Ankara, running to be his vice-presidents. Several smaller parties to the CHP's right are running on its lists in the upcoming parliamentary election including DEVA, Future, Felicity, Democrat, and Change in Turkey. Kılıçdaroğlu and his counterpart in the Good Party Meral Akşener continue a close cooperation as leaders of opposition parties, and the two parties are gaining support especially amongst the youth,[38][39][40][41][42] due to the ongoing economic crisis and government mismanagement of the COVID-19 pandemic.[43]

Ideology and political positions

Domestic

The Republican People's Party is a centre-left[44] political party that espouses social democracy[45][46] and Kemalism.[47] The CHP describes itself as a ''modern social-democratic party, which is faithful to the founding principles and values of the Republic of Turkey".[48][49]

The distance between the party administration and many leftist grassroots, especially left-oriented Kurdish voters, contributed to the party's shift away from the political left.[50] Leftists criticize the party's continuous opposition to the removal of Article 301 of the Turkish penal code, which caused people to be prosecuted for "insulting Turkishness" including Elif Şafak and Nobel Prize winner author Orhan Pamuk, its conviction of Turkish-Armenian journalist Hrant Dink, its attitude towards minorities in Turkey, as well as its Cyprus policy.

Numerous politicians from the party have espoused support for LGBT rights,[51][52][53] and the feminist movement in Turkey.

Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu has repeatedly called for Selahattin Demirtaş and Osman Kavala to be released from jail.[54]

Foreign

The party holds a significant position in the Socialist International,[55] Progressive Alliance[56] and is an associate member of the Party of European Socialists. In 2014 the CHP urged the Socialist International to accept the Republican Turkish Party of Northern Cyprus as a full member.[57]

The CHP generally votes with the government in foreign policy, and supports Turkey's interventions in Syria, Libya, and, up until 2021, Iraq.[58]

The party is pro-European and supports Turkish membership to the European Union.[59]

Electorate

.jpg.webp)

The CHP draws its support from professional middle-class secular and liberally religious voters. It has traditional ties to the middle and upper-middle classes such as white-collar workers, retired generals, and government bureaucrats as well as academics, college students, left-leaning intellectuals and labour unions such as DİSK.[60]

The party also appeals to minority groups such as Alevis. According to The Economist, "to the dismay of its own leadership the CHP's core constituency, as well as most of its MPs, are Alevis."[61] The party's leader, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, is also an Alevi himself.[62]

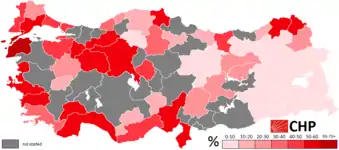

The CHP also draws much of their support from voters of big cities and coastal regions. The party's strongholds are the west of the Aegean Region (İzmir, Aydın, Muğla), the northwest of the Marmara Region (Turkish Thrace; Edirne, Kırklareli, Tekirdağ, Çanakkale), the east of the Black Sea Region (Ardahan and Artvin), and the Anatolian college town of Eskişehir.[63]

Party leaders

| No. | Name (Born–Died) |

Portrait | Term in Office | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881–1938) |  | 9 September 1923 | 10 November 1938 |

| 2 | İsmet İnönü (1884–1973) |  | 26 December 1938 | 8 May 1972 |

| 3 | Bülent Ecevit (1925–2006) | .jpg.webp) | 14 May 1972 | 30 October 1980 |

| Party closed down following the 12 September 1980 coup d'état | ||||

| 4 | Deniz Baykal (1938–2023) |  | 9 September 1992 | 18 February 1995 |

| 5 | Hikmet Çetin (1937–) |  | 18 February 1995 | 9 September 1995 |

| (4) | Deniz Baykal (1938–2023) |  | 9 September 1995 | 23 May 1999 |

| 6 | Altan Öymen (1932–) | .jpg.webp) | 23 May 1999 | 30 September 2000 |

| (4) | Deniz Baykal (1938–2023) |  | 30 September 2000 | 10 May 2010 |

| 7 | Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu (1948–) |  | 22 May 2010 | Incumbent |

Election results

General elections

| General election record of the Republican People's Party (CHP) 0–10% 10–20% 20–30% 30–40% 40–50% 50–60% 60–70% | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election | Leader | Vote | Seats | Changes | Result | Position | Map | ||||

| 1927 |  Mustafa Kemal Atatürk | — | 335 / 335 |

— | Majority government |  | |||||

| 1931 | — | 287 / 317 |

— | Majority government |  | ||||||

| 1935 | — | 401 / 428 |

— | Majority government |  | ||||||

| 1939 |  İsmet İnönü | — | unknown / 470 | — | — | Majority government |  | ||||

| 1943 | — | unknown / 492 | — | — | Majority government |  | |||||

| 1946 | — | 397 / 503 |

— | Majority government | |||||||

| 1950 | 3,176,561 | 69 / 492 |

39.45% | Main opposition |  | ||||||

| 1954 | 3,161,696 | 31 / 537 |

35.36% | Main opposition |  | ||||||

| 1957 | 3,753,136 | 178 / 602 |

41.09% | Main opposition |  | ||||||

| 1961 | 3,724,752 | 173 / 450 |

36.74% | Coalition government |  | ||||||

| 1965 | 2,675,785 | 134 / 450 |

28.75% | Main opposition |  | ||||||

| 1969 | 2,487,163 | 143 / 450 |

27.37% | Main opposition | |||||||

| 1973 | .jpg.webp) Bülent Ecevit | 3,570,583 | 185 / 450 |

33.30% | Coalition goverment |  | |||||

| 1977 Turkish general election |  6,136,171 | 213 / 450 |

41.38% | Minority government |  | ||||||

| 6 November 1983 | Party closed following the 1980 Turkish coup d'état and succeeded by the Populist Party (1983–85), the Social Democracy Party (1983-85) and the Social Democratic Populist Party (SHP) in 1985 after the latter two parties merged. The CHP was re-established in 1992 by dissident SHP members after banned political parties were allowed to re-establish, with the SHP and CHP merging in 1995. | ||||||||||

| 29 October 1987 | |||||||||||

| 20 October 1991 | |||||||||||

| 24 December 1995 |  Deniz Baykal |  3,011,076 | 49 / 550 |

10.71% | Opposition |  | |||||

| 18 April 1999 |  2,716,094 | 0 / 550 |

8.71% | Extra-parliamentary opposition |  | ||||||

| 3 November 2002 |  6,113,352 | 178 / 550 |

19.39% | Main opposition |  | ||||||

| 22 July 2007 |  7,317,808 | 112 / 550 |

20.88% | Main opposition |  | ||||||

| 12 June 2011 |  Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu |  11,155,972 | 135 / 550 |

25.98% | Main opposition |  | |||||

| 7 June 2015 |  11,518,139 | 132 / 550 |

24.95% | Main opposition |  | ||||||

| 1 November 2015 |  12,111,812 | 134 / 550 |

25.32% | Main opposition | .png.webp) | ||||||

| 24 June 2018 |  11,348,899 | 146 / 600 |

22.64% | Main opposition |  | ||||||

| 14 May 2023 | 13,655,909 |

TBD | 25.57% |

TBD | |||||||

Presidential elections

| Presidential election record of the Republican People's Party (CHP) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election | Candidate | Votes | % | Outcome | Map | |

| 10 August 2014 | _(cropped).jpg.webp) Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu Cross-party with MHP | 15,587,720 | 38.44% | 2nd |  | |

| 24 June 2018 | .jpg.webp) Muharrem İnce | 15,340,321 | 30.64% | 2nd |  | |

| 14 May 2023 | .png.webp) Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu |

TBD | TBD | TBD |  | |

Senate elections

| Election date | Party leader | Number of votes received | Percentage of votes | Number of senators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1961 | İsmet İnönü | 3,734,285 | 36,1% | 36 / 150 |

| 1964 | 1,125,783 | 40,8% | 19 / 51 | |

| 1966 | 877,066 | 29,6% | 13 / 52 | |

| 1968 | 899,444 | 27,1% | 13 / 53 | |

| 1973 | Bülent Ecevit | 1,412,051 | 33,6% | 25 / 52 |

| 1975 | 2,281,470 | 43,4% | 25 / 54 | |

| 1977 | 2,037,875 | 42,4% | 28 / 50 | |

| 1979 | 1,378,224 | 29,1% | 12 / 50 |

Local elections

| Election date | Party leader | Provincial council votes | Percentage of votes | Number of municipalities | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1963 | İsmet İnönü | 3,458,972 | 36,22% | 335 / 1,045 | |

| 1968 | 2,542,644 | 27,90% | 289 / 1,252 | ||

| 1973 | Bülent Ecevit | 3,708,687 | 37,09% | 551 / 1,640 | |

| 1977 | 5,161,426 | 41,73% | 714 / 1,730 | ||

| 1984 | Party closed following the 1980 Turkish coup d'état until 1993. | ||||

| 1989 | |||||

| 1994 | Deniz Baykal | 1,297,371 | 4,61% | 64 / 2,710 | |

| 1999 | 3,487,483 | 11,08% | 373 / 3,215 | ||

| 2004 | 5,848,180 | 18,38% | 467 / 3,193 | ||

| 2009 | 9,233,662 | 23,11% | 503 / 2,903 | ||

| 2014 | Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu | 10,938,262 | 26,34% | 226 / 1,351 |  |

| 2019 | 12,625,346 | 29,36% | 240 / 1,355 |  | |

See also

References

- Yenen, Alp (2018). "Elusive forces in illusive eyes: British officialdom's perception of the Anatolian resistance movement". Middle Eastern Studies. 54 (5): 788–810. doi:10.1080/00263206.2018.1462161. hdl:1887/74261. S2CID 150032953.

- Zürcher, Erik J. (1992). "The Ottoman Legacy of the Turkish Republic: An Attempt at a New Periodization". Die Welt des Islams. 32 (2): 237–253. doi:10.2307/1570835. ISSN 0043-2539. JSTOR 1570835.

- Üngör, Uğur Ümit (2008). "Geographies of Nationalism and Violence: Rethinking Young Turk 'Social Engineering'". European Journal of Turkish Studies. Social Sciences on Contemporary Turkey (7). doi:10.4000/ejts.2583. ISSN 1773-0546.

- "Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi" (in Turkish). Court of Cassation. Retrieved January 10, 2022.

- "The Republican People's Party (CHP) is Complicit in the Erosion of Democracy in Turkey". Georgetown Journal of International Affairs. 6 August 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- Ciddi, Sinan (2009). Kemalism in Turkish Politics: The Republican People's Party, Secularism and Nationalism. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-47504-4.

- "History of the CHP". chp.org.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 18 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Murat Sofuglu (26 January 2018). "Turks still debate whether Treaty of Lausanne was fair to Turkey". TRT World. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- Murat Sofuglu (26 January 2018). "Turks still debate whether Treaty of Lausanne was fair to Turkey". TRT World. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- Malik Mufti (2009). Daring and Caution in Turkish Strategic Culture: Republic at Sea. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 233. ISBN 9780230236387.

- Bali, Rifat N. Kieser, Hans-Lukas (ed.). Turkey Beyond Nationalism. I.B. Tauris. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-84511-141-0.

- Macfie, A.L. (2014). Atatürk. Routledge. p. 182. ISBN 978-1-138-83-647-1.

- Demirci, Fatih Kadro Hareketi ve Kadrocular, Dumlupınar Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 2006, sayı 15.

- Ergüder, J. 1927 Komünist Tevkifatı, "İstanbul Ağır Ceza Mahkemesindeki Duruşma", Birikim Yayınları, İstanbul, 1978

- Başvekalet Kararlar Dairesi Müdürlüğü 15 Aralık 1937 tarih, 7829 nolu kararname. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- Adem, Mahmut. "İsmet İnönü'nün Cumhurbaşkanlığı Döneminde Yükseköğretimdeki Gelişmeler (1938-1950)". İnönü Vakfı. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017.

- Akşin, Sina. "I. DEVRİM YOLU ve KARŞI-DEVRİM GİRİŞİMLERİ". İnönü Vakfı. Archived from the original on 7 May 2017.

- Manuel Álvarez-Rivera. "Election Resources on the Internet: Elections to the Turkish Grand National Assembly". Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- "İnönü'nün MBK'ye gönderdiği Menderes mektubu". Ensonhaber. 24 September 2012.

- "İnönü'nün MBK'ye gönderdiği Menderes mektubu". Ensonhaber. 24 September 2012.

- Gülsüm Tütüncü Esmer. "Propaganda, Söylem ve Sloganlarla Ortanın Solu" (PDF) (in Turkish). Dokuz Eylül University. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- İsmet İnönü foundation page by Şerafettin Turan (in Turkish)

- Ustel, Aziz (14 July 2008). "Savcı, Ergenekon'u Kenan Evren'e sormalı asıl!". Star Gazete (in Turkish). Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- Ciddi, Sinan (13 January 2009). Kemalism in Turkish Politics: The Republican People's Party, Secularism and Nationalism. Routledge. p. 79. ISBN 9781134025596.

- Ciddi, Sinan (13 January 2009). Kemalism in Turkish Politics: The Republican People's Party, Secularism and Nationalism. Routledge. p. 79. ISBN 9781134025596.

- Goksedef, Ece (19 April 2023). "Turkey's soft-spoken Kemal Kilicdaroglu takes on powerful Erdogan". British Broadcasting Corperation.

- Çarkoğlu, Ali (20 October 2009). "A New Electoral Victory for the 'Pro-Islamists' or the 'New Centre-Right'? The Justice and Development Party Phenomenon in the July 2007 Parliamentary Elections in Turkey". South European Society and Politics. 12 (4): 501–519. doi:10.1080/13608740701731457. S2CID 153992923 – via Taylor & Francis.

- Çarkoğlu, Ali (20 October 2009). "A New Electoral Victory for the 'Pro-Islamists' or the 'New Centre-Right'? The Justice and Development Party Phenomenon in the July 2007 Parliamentary Elections in Turkey". South European Society and Politics. 12 (4): 501–519. doi:10.1080/13608740701731457. S2CID 153992923 – via Taylor & Francis.

- Koylu, Hilal. "Köşk'e ilk davet eşsiz". Radikal (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- "Turkey to add Gülen movement to list of terror groups: President". Hurriyet Daily News. 27 May 2016.

- "Turkish Parliament Refuses to Allow U.S. Troops In". Deutsche Welle. 3 November 2003.

- "Turkish opposition leader quits over 'sex tape'". BBC News. 10 May 2010.

- Bozarslan, Mahmut. "In Turkey, Erdogan challenger attracts solid Kurdish support, a decisive vote". Al-Monitor.

- Toksabay, Ece (25 August 2016). "Turkish opposition leader targeted by Kurdish militants - minister". Reuters.

- Zaman, Amberin. "Meet Kemal Kilicdaroglu, Turkey's long-derided opposition head who could dethrone Erdogan". Al-Monitor.

- "The "Nation Alliance" officially forms". amp.dw.com (in Turkish). Retrieved 18 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "'Millet ittifakı' resmen kuruldu: Protokolün detayları ortaya çıktı". cumhuriyet.com.tr. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- "AKP'de Z kuşağı endişesi Erdoğan'a şarkı söylettirdi". cumhuriyet.com.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- "Son anket: Yandaş anket şirketinden Erdoğan'a kötü haber!". cumhuriyet.com.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- "CHP'nin oyları yükseliyor!". Yurt Gazetesi (in Turkish). Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- "Metropoll'den gündeme damga vuracak 'Z kuşağı' anketi: 'Kararsız', 'protesto oy' ve 'cevap yok' şıkkına yüklendiler". Haberler.com (in Turkish). 5 July 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- "Turkey's Generation Z: A Youth Challenge to Erdoğan". Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies. 10 August 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- "Dar gelirli seçmen anketi: AKP düşüyor, HDP yükselişte". Tele1 (in Turkish). 9 September 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- Uras, Umut (29 March 2019). "New test for Erdogan: What's at stake in Turkish local elections?". Istanbul: Al Jazeera. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- "Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi – Parti İçi Eğitim Birimi" (PDF).

- "The Republican People's Party (CHP) is Complicit in the Erosion of Democracy in Turkey". Georgetown Journal of International Affairs. 6 August 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- Liza Mügge (2013). "Brussels Calling: The European organisation of migrants from Turkey". In Dirk Halm; Zeynep Sezgin (eds.). Migration and Organized Civil Society: Rethinking National Policy. Routledge. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-136-24650-0.

- Seçim Bildirgesi (Election Manifesto), Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi, page 4. (in Turkish) Archived 27 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Nordsieck, Wolfram (2018). "Turkey". Parties and Elections in Europe. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

- Güneş Ayata (1992). CHP (Örgüt ve İdeoloji). Gündoğan Yayınları. p. 320. ISBN 9755200452.

- "CHP'li Böke'den Alperen Ocakları'na sert tepki: Tehdide seyirci kalmayız".

- "CHP'li Mahmut Tanal 'Trans Onur Yürüyüşü'nde TOMA'nın üzerine çıktı".

- "CHP'den LGBT'ler için İş Kanunu teklifi".

- "Main opposition leader calls for release of Kavala, Demirtaş". Duvar English. 21 October 2021.

- Socialist International – List of member parties Archived 7 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Parties & Organisations". Progressive Alliance. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- "Parti Tüzüğü" (in Turkish). cumhuriyetciturkpartisi.org. 22 May 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- "Turkey extends Syria and Iraq military missions by two years". Al Jazeera. 26 October 2021.

- Alfred Stepan; Ahmet T. Kuru, eds. (2012). "The European Union and the Justice and Development Party". Democracy, Islam, and Secularism in Turkey. Columbia University Press. p. 184, paragraph 2. ISBN 9780231159333.

- "CHP'li Kani Beko: Grevin kazananı olmaz" (in Turkish). t24.com.tr. 3 March 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- "Identity: Proud to be a Turk: But what does it mean?". The Economist. 6 February 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- "Kılıçdaroğlu Alevi olduğu için Erdoğan yüzde 67 oy alacak". odatv.com (in Turkish). Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- "CHP Seçim Sonuçları: 31 Mart 2019 CHP Yerel Seçim Sonuçları". Sözcü (in Turkish). Retrieved 18 September 2021.

.svg.png.webp)