Yuanlingshan

Yuanlingshan (Chinese: 圓領衫; pinyin: yuánlǐngshān; lit. 'round collar jacket') is a form of round-collared upper garment (called shan) in Hanfu; it is also referred to as yuanlingpao (Chinese: 圓領袍; pinyin: yuánlǐngpáo; lit. 'round collar gown/robe') or panlingpao (Chinese: 盤領袍; pinyin: pánlǐngpáo) when used as a robe (called paofu[1]: 17 ).[2][3] The yuanlingshan and yuanlingpao were both developed under the influence of Hufu from the Donghu people in the early Han dynasty[4] and later on by the Wuhu (including the Xianbei people) in the Six dynasties period.[4] The yuanlingpao is a formal attire usually worn by men, though it was also fashionable for women to wear it in some dynasties, such as in the Tang dynasty.[2] In the Tang dynasty, the yuanlingpao could also transform into the fanlingpao.[5]

| Yuanlingshan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Men wearing yuanlingpao, Tang dynasty painting, 706 AD. | |||||||

Woman wearing a yuanlingshan with skirt, Ming dynasty | |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 圓領衫 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 圆领衫 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Round collar shirt | ||||||

| |||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 圓領袍 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 圆领袍 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Round collar robe/ Round collar gown | ||||||

| |||||||

| Third alternative Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 盤領袍 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 盘领袍 | ||||||

| |||||||

| English name | |||||||

| English | Round collar robe | ||||||

There are also specific forms of yuanlingpao and yuanlingshan which are named based on its decorations and construction; for example, the panling lanshan (Chinese: 盤領襴衫), also called lanshan (Chinese: 襴衫) for short,[6][3] bufu,[7]: 185–186 wulingshan (Chinese: 無領衫; lit. 'collarless shirt'),[8][9] longpao (Chinese: 龍袍; lit. 'dragon robe'), and mangfu (Chinese: 蟒服; lit. 'python clothing').

Terminology

The term yuanlingshan is literally translated as "round collar shirt", being composed of the Chinese characters yuanling (Chinese: 圆领; lit. 'Round collar'), which literally translates to round collar and shan (Chinese: 衫), literally translated as "shirt".

The term yuanlingpao is literally translated as "round collar robe (or gown)", being composed of the Chinese characters yuanling and pao (Chinese: 袍), an abbreviation for the term paofu (Chinese: 袍服), which is literally translated as "robe" or "gown".

The term panling lanshan (Chinese: 盤領襴衫) or lanshan (Chinese: 襴衫) refers to a specific form of yuanlingpao with bottom horizontal band attached at the knee-level and follows the shenyi system.[6][3]

The term bufu (Chinese: 补服) is generic term which refers to clothing decorated with a rank badge called buzi (Chinese: 补子; pinyin: bǔzi), which is typically a mandarin square or roundels, to indicate its wearer's rank.[10]: 64 [7]: 185–186 They were typically worn by government officials.[7]: 185–186

When a yuanlingpao or yuanlingshan is decorated with Chinese dragons called long (simplified Chinese: 龙; traditional Chinese: 龍) or decorated with mang (Chinese: 蟒; lit. 'python') decorations (including in the forms of roundels or square rank badge), the generic term longpao or "mangfu" is applied respectively depending on the number of dragon-claws used and the period of time.[note 1]

History

Han dynasty

The yuanlingpao and yuanlingshan were both a common form of clothing for the Hu people.[4] During the Eastern Han dynasty, some forms of Hanfu started to be influenced by the Hufu of the Hu people, and garments with yuanling started to appear.[4] However, in this period, the yuanlingpao was typically used as an undergarment.[4][11] The collar of the Han dynasty yuanlingpao were not turned on both sides and the shape of its edges were similar to the styles worn in the Sui and Tang dynasties.[4] It was also during the early years of the Han dynasty that the shape of the yuanlingpao worn in the later dynasties, such as in the Ming dynasties, started to develop.[11]

Wei, Jin, Northern, and Southern dynasties / Six dynasties

It was only in the era of the Six dynasties that the yuanlingpao began to be worn as an outer garment[11] under the influence of the culture of ethnic minorities (Wuhu) which founded the minority nationalities regime in the Wei and Jin dynasties period.[4] It is also during the Six dynasties period that the yuanlingpao started to be worn as a form of formal clothing.[11] Thus, these ethnic minorities also played a significant role in laying the foundation for the popularity of the yuanlingpao used in the subsequent dynasties.[4]

Influence of the Xianbei

When the Wuhu entered the Central plains, their dressing culture influenced the clothing culture of the Han people in the Central plains.[4] These northern nomads, including the Xianbei, also introduced new clothing styles, including a form of clothing referred as quekua (Chinese: 缺胯), a form of crotch-length long jacket with either round or snug (plunged) collar with tight sleeves and less overlap than the traditional Hanfu allowing for greater ease of freedom (especially when horse riding) and which strongly impacted Chinese fashion.[12]: 317

.jpg.webp)

The Northern Wei period was marked by the cultural integration between the Xianbei and the Han Chinese. The Xianbei ruling elites adopted Chinese clothing and Chinese customs; in addition, the Han Chinese started to integrate some of the Xianbei's nomadic style clothing, which included high boots and the yuanlingpao and/or yuanlingshan with narrow sleeves, into Han clothing.[13]: 183, 185–186 In the Northern Wei, however, the yuanlingpao worn by unearthed terracotta warriors were closed in the zuoren-style instead of youren-style, which reflects its Hufu characteristics.[note 2][5] Since the Northern Wei dynasty, the shapes of the Han Chinese's paofu also started to be influenced by the yuanlingpao-style robe which originated in Western Asia and were then spread to the East through the Sogdians of Central Asia.[5]

In the Northern and Southern dynasties, the yuanlingpao of the Xianbei was localized by the Han Chinese losing the connotation of being Hufu and developed into a new form of Hanfu, called panling lanshan, through the addition of a new seam structure called lan (Chinese: 襕; pinyin: Lán) which conforms to the tradition of the Hanfu and by following the Han Chinese's shenyi system.[6][3]

.jpg.webp) Yuanlingpao worn by an acrobat figure, Northern Wei

Yuanlingpao worn by an acrobat figure, Northern Wei Women wearing yuanlingshan with skirt, Northern Wei, Datong.

Women wearing yuanlingshan with skirt, Northern Wei, Datong..jpg.webp) Xianbei men wearing quekua in the form yuanlingpao, Fresco from the Tomb of Lou Rui, Northern Qi (550-577 AD)

Xianbei men wearing quekua in the form yuanlingpao, Fresco from the Tomb of Lou Rui, Northern Qi (550-577 AD) Xianbei men wearing quekua in the form of yualingpao and the lapel gown, Northern Qi.

Xianbei men wearing quekua in the form of yualingpao and the lapel gown, Northern Qi.

Influence of the Sogdians

The Sogdians and their descendants (mostly from the merchant class) who lived in China during this period also wore a form of knee-length, yuanling-style kaftan that retained their own ethnic characteristics but also showed some influences from East Asia (i.e., Chinese and early Turks).[14] Under the influence and the demands of the Chinese population, most Sogdian attire in China had to be closed to the right in the youren-style.[14] Their kaftan would often be buttoned up the neck forming the round collar but occasionally the collar (or lower button) would be undone to form lapel robes,[14][5] a style sometimes referred as fanlingpao (Chinese: 翻领袍; pinyin: fānlǐngpáo; lit. 'Lapel robe'). This dressing custom of wearing fanlingpao-style robes was later inherited and developed into the yuanlingpao of the subsequent Tang and Sui dynasties.[5]

Sui and Tang dynasties, Five dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period

In the Tang dynasty, the descendants of the Xianbei and the other non-Chinese people who ruled northern China from 304 – 581 AD lost their ethnic identity and became Chinese; the term Han was used to refer to all people of the Tang dynasty instead of describing the population ruled by the Xianbei elites during the Northern dynasties.[15]

The yuanlingpao and yuanlingshan, tied with a belt (typically a leather belt[16]) at the waist, became a typical form of fashion for both Tang dynasty men and women as it was fashionable for women to dress like men in this period.[1]: 34–36 [2] Both the yuanlingpao and the yuanlingshan also became the main form of clothing for men.[16] Both the yuanlingpao and yuanlingshan of this period had a long and straight back and front with a border at the collar; the front and back of the garments each have a piece of fabric attached in order to tied the clothing around the waist; the sleeves could be tight or loose; if the sleeves were tight, they were designed to facilitate its wearer's ease of movements.[16] Trousers were worn under the yuanlingpao.[2] Some women also wore banbi under their yuanlingpao.[17]

A male ride wearing a yuanlingshan, Tang dynasty

A male ride wearing a yuanlingshan, Tang dynasty Eunuchs wearing yuanlingpao with loose sleeves, Tang dynasty tomb, 706 AD.

Eunuchs wearing yuanlingpao with loose sleeves, Tang dynasty tomb, 706 AD. Women (middle and right) wearing yuanlingpao with tight and narrow long sleeves, Tang dynasty tomb, 706 AD.

Women (middle and right) wearing yuanlingpao with tight and narrow long sleeves, Tang dynasty tomb, 706 AD. Servant girl wearing a yuanlingpao with loose sleeves, Tang dynasty painting, mid 8th century AD.

Servant girl wearing a yuanlingpao with loose sleeves, Tang dynasty painting, mid 8th century AD. Servant girl with loose sleeves yuanlingpao, Tang dynasty, mid 8th century AD.

Servant girl with loose sleeves yuanlingpao, Tang dynasty, mid 8th century AD..jpg.webp) Woman cross-dressing; she is wearing a banbi under her yuanlingpao; Tang dynasty.

Woman cross-dressing; she is wearing a banbi under her yuanlingpao; Tang dynasty. Emperor Yizong of Tang, late Tang dynasty.

Emperor Yizong of Tang, late Tang dynasty. Tomb of Wang Chuzhi, Five dynasties and ten kingdoms period.

Tomb of Wang Chuzhi, Five dynasties and ten kingdoms period. Polo players wearing yuanlingpao with tight sleeves on horseback, Tang dynasty

Polo players wearing yuanlingpao with tight sleeves on horseback, Tang dynasty

A horizontal band, one distinguishing feature of men's Tang dynasty clothing, could also be attached to the lower region of the yuanlingpao.[18]: 81 In the Tang dynasty, a long, red panling lanshan with long sleeves was worn by the scholars and government officials; it was worn together with a headwear called futou.[19] In 630 during the 4th year of Zhen Guan, colours regulations for the panling lanshan of the officials were decreed: purple for the 3rd and 4th rank officials; bright red for the 5th rank officials; green for the 6th and 7th rank officials; and blue for the 8th and 9th officials.[18]: 81 In the Kaiyuan era (713 – 741 AD), slaves and the common soldiers also started to wear the scholar's panling lanshan.[20]

Panling lanshan, Tang dynasty.

Panling lanshan, Tang dynasty. Mourning attendant wearing panling lanshan, Tang Dynasty

Mourning attendant wearing panling lanshan, Tang Dynasty A Tang dynasty man (middle) wearing a panling lanshan, notice the large horizontal band at the bottom of the robe.

A Tang dynasty man (middle) wearing a panling lanshan, notice the large horizontal band at the bottom of the robe.

Foreign influences

In the Tang dynasty, it was also popular for people to use fabrics (such as brocade) to decorate the collars, sleeves and front of the yuanlingpao; this form of clothing decoration customs is known as 'partial decorations of gowns' and was influenced by the Sogdians of Central Asia who had entered China since the Northern and Southern dynasties period.[21] Influenced by foreign cultures,[21] some yuanlingpao could have a band of fabric decorated with Central Asian roundels which would run down at the centre of the robe as a form of partial decoration.[17]

It was also popular to wear Hufu.[20] Almost all figurines and mural paintings depicting female court attendants dressed in men's clothing are wearing Hufu.[17] The Hufu which was popular in this period was the clothing worn by the Tartars and the people who lived in the Western regions,[22] which was brought from the Silk Road.[23] The double overturned lapels with tight-fitting sleeves was known as kuapao, a robe which originated from Central Asia.[24] During this period, the yuanlingpao could be turned into a fanlingpao under the influence of Hufu by unbuttoning the robes; the fanlingpao could be also be turned back into a yuanlingpao when buttoned.[5] In some unearthed pottery figures wearing fanlingpao dating from the Tang dynasty, it was found that the yuanlingpao had three buttons on the collar.[5] After the High Tang dynasty period, the influences of Hufu progressively started to fade and the clothing started to become more and more loose.[22]

Song dynasty

During the Song dynasty, the official dress worn by Song court officials were the yuanlingpao with long, loose and broad sleeves.[25]: 275 [26]: 3 The colours of the yuanlingpao were also regulated based on the official's ranks.[25]: 275 [26]: 3 The yuanlingpao had a large overlapping region being held down by a broad strip of fabric;[26]: 3 it also had a long line which divided the front part of the gown.[25]: 275 Kerchief (typically futou), leather belt, and yudai (Chinese: 魚袋; lit. 'fish-bag'), black hide boots or shoes, would be worn by the court officials as accessories.[25]: 275 [26]: 3

Maids of Song dynasty empress wearing yuanlingpao.

Maids of Song dynasty empress wearing yuanlingpao. Northern Song Male buddhist donor with a loose-sleeved dark yuanlingpao.

Northern Song Male buddhist donor with a loose-sleeved dark yuanlingpao. Emperor Taizong of Song wearing a very large sleeved yuanlingpao.

Emperor Taizong of Song wearing a very large sleeved yuanlingpao. Song dynasty Emperor Duzong wearing a very large sleeved yuanlingpao.

Song dynasty Emperor Duzong wearing a very large sleeved yuanlingpao.

Liao dynasty

Khitan men wore the Khitan-style yuanlingpao with a belt at their waist and trousers tucked into felt boots.[27]: 46 [28] The Khitan-style yuanlingpao differed from those worn by the Han Chinese.[29] In terms of design and construction, the yuanlingpao of the Khitan had both back and side slits; the side slits are found at the lower region of the robes.[30] The back slits facilitated horse-riding and protected their legs from the cold.[29] Some of them had no slits.[30] Their yuanlingpao had narrow sleeves,[28] closed on the left side,[30] was unadorned.[29]

Khitan men wearing tight sleeves yuanlingpao, Liao dynasty.

Khitan men wearing tight sleeves yuanlingpao, Liao dynasty. Khitan guard wearing tight sleeves yuanlingpao, Liao dynasty.

Khitan guard wearing tight sleeves yuanlingpao, Liao dynasty. Khitan men wearing tight sleeves yuanlingpao

Khitan men wearing tight sleeves yuanlingpao

Jin dynasty

Men wearing yuanlingpao, Jurchen Jin dynasty,

Men wearing yuanlingpao, Jurchen Jin dynasty,

Western Xia

.jpg.webp) Men wearing round collar robe, Western Xia mural.

Men wearing round collar robe, Western Xia mural. Western xia men wearing tight sleeves yuanligpao.

Western xia men wearing tight sleeves yuanligpao.

Yuan dynasty

Ming dynasty

Following the founding of the Ming dynasty, the emperor restored the old system of the Tang and Song dynasties.[11] The yuanlingpao and yuanlingshan are also the most common form of attire for both male and female, officials, and nobles during the Ming Dynasty. The yuanlingpao and/or yuanlingshan were not typically worn alone; underneath, a sleeveless vest called dahu and an inner robe (either the tieli or zhishen) could also be worn.

The difference between yuanlingpao or yuanlingshan of the civilians and the officials (and nobles) is the use of a buzi (either a mandarin square or roundels rank badge[10]: 64 ) on it and the fabric materials used.[11][note 3] The clothing of the Ming dynasty were predominantly red in colour.[11] However, there was also strict colour regulations and specific colours were used on the yuanlingshan or yuanlingpao depending on the ranks of officials.[11][note 4] During an Imperial Funeral, Ming officers wore a grey blue yuanlingshan without a Mandarin square, wujiaodai (Chinese: 烏角帶; pinyin: wūjiǎodài; lit. 'black horn belt') and wushamao. This set was known as Qingsufu (Chinese: 青素服).

The Ming dynasty yuanlingpao and yuanlingshan were typically characterized by the "cross plane structure" with the back and front being bounded by the middle seam of the sleeves, symmetrical front and back and the left and right side are more or less symmetrical; there is a centre-line which is the axis of this symmetry.[11] It has a round collar without a high-standing collar which is secured with button; it overlaps on the front side and closes at the right side in the youren-style, which follows the traditional Hanfu system.[11] It also have side slits on the right and left side. The sleeves of the yuanlingshan are mostly in a style called pipaxiu (Chinese: 琵琶袖; pinyin: pípáxiù; lit. 'pipa sleeves'), which means the sleeves are large but curved to form a narrow sleeve cuff, to facilitate movements and be more practical in daily lives.[11] Men's yuanlingpao and yuanlingshan also have side panels called anbai (Chinese: 暗擺; pinyin: ànbǎi; lit. 'hidden pendulum') at the side slits to conceal the undergarments.[11] These side panels are also referred as 'side ears' which are unique structures in the Ming dynasty's yuanlingpao; this specific structure reflect the combination Hanfu and ethnic minority costumes (i.e. the Mongols).[11] The 'side ear' also allows for greater ease of movement and can increase the looseness of robe.[11]

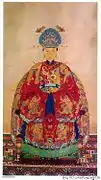

A noblewomen yuanlingpao, Ming dynasty.

A noblewomen yuanlingpao, Ming dynasty.

Unearthed Ming dynasty artifact.

Unearthed Ming dynasty artifact. Ming dynasty court official.

Ming dynasty court official. Ming Emperor wearing the round-collar robes decorated with dragon roundels. This form of dress is called the longpao (i.e., the dragon robes)

Ming Emperor wearing the round-collar robes decorated with dragon roundels. This form of dress is called the longpao (i.e., the dragon robes).jpg.webp) Round collared robe, from the Tomb of Emperor Wanli, Ming dynasty.

Round collared robe, from the Tomb of Emperor Wanli, Ming dynasty. Yuanlingshan artifact.

Yuanlingshan artifact.

Qing dynasty

During the Qing dynasty, the Manchu rulers enforced the tifayifu policy along with the 10 exemptions; among the exempted people were the Han Chinese women who were allowed to continue wearing the Ming-style Hanfu and the theatre performers on-stage.[31][32] While qizhuang was used in dominant sphere of society (ritual and official locations), Hanfu continued to be used in the subordinate societal sphere, such as in women's quarters and theatres.[31]

Yuanlingpao (court robe), Qing dynasty, 19th century.[33]

Yuanlingpao (court robe), Qing dynasty, 19th century.[33] A woman's wedding yuanlingshan, also known as mangao, closes with buttons on the right side. It was typically worn together with a skirt known as mangchu

A woman's wedding yuanlingshan, also known as mangao, closes with buttons on the right side. It was typically worn together with a skirt known as mangchu A child yuanlingpao, 19th century

A child yuanlingpao, 19th century.jpg.webp) Hong Xiuquan's silk Dragon robe

Hong Xiuquan's silk Dragon robe

Wedding garment

Officials' and/or the nobles' yuanlingpao were also a form of wedding attire for commoners. The groom wears a wushamao and the yuanlingpao of a 9th rank official robe. The bride wears the fengguan and a red yuanlingpao or yuanlingshan with the xiapei of a noblewoman.

Influence and derivatives

Dallyeong

In Korea, the yuanlingpao was introduced during the Tang dynasty into what is known as the dallyeong (Korean: 단령; Hanja: 團領; RR: danryeong; Korean pronunciation: [daɭjʌoŋ]).[34] During the rule of Queen Jindeok of Silla, Kim Chunchu personally travelled to the Tang dynasty to request for clothing and belts and voluntarily accepted the official uniform system of the Tang dynasty; this included the dallyeong among many other clothing items.[35] Since then, the dallyeong continued to be worn until the end of Joseon.[34] Under the reign of King U in late Goryeo, the dallyeong was adopted as an official gwanbok when the official uniform system of the Ming dynasty was imported.[36]

Wonsam

The initial shape of the wonsam worn by women from the 15th to 16th century was similar to the dallyeong and included the use of collar which was similar to the dallyeong-style collar.[37]

Japan

In Japan, the formal court attire for men and women was established by the start of the 8th century and was based on the court attire of the Tang dynasty.[38] The round collared robe called ho in the Sokutai (束帯), which was worn by the Japanese Emperors, and the noblemen,[39] was adopted from the yuanlingpao.[40]

According to the Ming dynasty's Government letter against Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the Ming Government bestowed on him a set of changfu (Chinese: 常服羅) containing a red yuanlingpao with qilin mandarin square (Chinese: 大紅織金胷背麒麟圓領), a dark blue dahu (Chinese: 青褡護), and a green tieli (Chinese: 綠貼裏).

Áo viên lĩnh

According to the book Weaving a realm by the Vietnam Center, the áo viên lĩnh (Hán tự: 襖圓領), a 4-long flap robe with round neck,[41] was imported to Vietnam from China.[42] However, this fashion gradually faded away from their daily lives due to the clothing reforms decreed by the Nguyen lords.[42]

Men wearing áo viên lĩnh, painting from The Mahasattva Trúc Lâm Coming Out of the Mountains, 1363.

Men wearing áo viên lĩnh, painting from The Mahasattva Trúc Lâm Coming Out of the Mountains, 1363. Áo viên lĩnh of Vietnamese people in Đàng Trong, 1675.

Áo viên lĩnh of Vietnamese people in Đàng Trong, 1675. Áo viên lĩnh in the Lê dynasty

Áo viên lĩnh in the Lê dynasty

See also

Notes

- A Chinese dragon can be found in with 3, 4 or 5 claws. From the ancient times to the Song dynasty, Chinese dragons were typically depicted with 3 claws. From the Ming dynasty, a Chinese dragon was defined as having 5 claws while the 4-clawed dragon was referred as mang (python). There is a clear difference between the Dragon robe and mangfu. See page Mangfu, Dragon robe, Japanese dragon for more details.

- Zuoren refers to having the garment closing on the left side while youren refers to having the garments closing on the right side.

- In the Ming dynasty, officials were silk or leno silk. The ordinary civilians however wore coarse clothing made of cotton and linen.

- According to the Ming dynasty regulations officials ranking from the 1st to 4th grades wore red; the 5th to 7th wore green, and the 8th to 9th also wore green.

References

- Hua, Mei (2011). Chinese clothing (Updated ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom. ISBN 978-0-521-18689-6. OCLC 781020660.

- Wang, Xinyi; Colbert, François; Legoux, Renaud (2020). "From Niche Interest to Fashion Trend: Hanfu Clothing as a Rising Industry in China". International Journal of Arts Management. 23 (1). Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- 유혜영 (1992). "돈황석굴벽화에 보이는 일반복식의 연구".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Wang, Fang (2018). "Study on Structure and Craft of Traditional Costumes of Edge" (PDF). Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Economics and Management, Education, Humanities and Social Sciences (EMEHSS 2018). Atlantis Press: 584–588. doi:10.2991/emehss-18.2018.118. ISBN 978-94-6252-476-7.

- Zhao, Qiwang (2020). "Western Cultural Factors in Robes of Wei, Jin, Southern and Northern Dynasties as Well as Sui and Tang Dynasties" (PDF). 2020 3rd International Conference on Arts, Linguistics, Literature and Humanities (ICALLH 2020). Francis Academic Press, UK: 141–147. doi:10.25236/icallh.2020.025 (inactive 31 December 2022).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of December 2022 (link) - "Chinese Traditional Costume - Lanshan for Scholars - 2022". www.newhanfu.com. 2020-11-28. Retrieved 2022-05-18.

- Introduction to Chinese culture : cultural history, arts, festivals and rituals. Guobin Xu, Yanhui Chen, Lianhua Xu, Kaiju Chen, Xiyuan Xiong, Wenquan Wu. Singapore. 2018. ISBN 978-981-10-8156-9. OCLC 1030303372.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - "Guide of the Ming Dynasty Shan/Ao Types for Girls - 2022". www.newhanfu.com. 2021-07-02. Retrieved 2022-06-13.

- "Guide to Hanfu Types Summary & Dress Codes (Ming Dynasty)". www.newhanfu.com. 2021-04-04. Retrieved 2022-06-13.

- China : a historical and cultural dictionary. Michael Dillon. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon. 1998. ISBN 0-7007-0438-8. OCLC 38866522.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Yang, Shuran; Yue, Li; Wang, Xiaogang (2021-08-01). "Study on the structure and virtual model of "xiezhi" gown in Ming dynasty" (PDF). Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 1986 (1): 012116. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1986/1/012116. ISSN 1742-6588. S2CID 236985886.

- Dien, Albert E. (2007). Six dynasties civilization. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07404-8. OCLC 72868060.

- Migration and membership regimes in global and historical perspective : an introduction. Ulbe Bosma, Kh Kessler, Leo Lucassen. Leiden: Brill. 2013. ISBN 978-90-04-25115-1. OCLC 857803189.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Yatsenko, Sergey A. (2012). "Sogdian Costume in Chinese and Sogdian Art of the 6th-8th centuries". Serica - Da Qin, Studies in Archaeology, Philology and History on Sino-Western Relations. G. Malinowski, A. Paron, B. Szmoniewski, Wroclaw (1 ed.). Wydawnictwo GAJT. pp. 101–114. ISBN 9788362584406.

- Holcombe, Charles (2018). A history of East Asia : from the origins of civilization to the twenty-first century. Cambridge University Press. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-1-107-11873-7. OCLC 1117553352.

- Zang, Yingchun (2003). Zhongguo chuan tong fu shi [中国传统服饰] [Chinese traditional costumes and ornaments]. 李竹润., 王德华., 顾映晨. (Di 1 ban ed.). Beijing: Wu zhou chuan bo chu ban she. ISBN 7-5085-0279-5. OCLC 55895164.

- Chen, Bu Yun (2013). Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) (Thesis). Columbia University. doi:10.7916/d8kk9b6d.

- 5000 years of Chinese costumes. Xun Zhou, Chunming Gao, 周汛, Shanghai Shi xi qu xue xiao. Zhongguo fu zhuang shi yan jiu zu. San Francisco, CA: China Books & Periodicals. 1987. ISBN 0-8351-1822-3. OCLC 19814728.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Ka Shing, Charles Ko (2014-01-01). "The Development of Academic Dress in China". Transactions of the Burgon Society. 14 (1). doi:10.4148/2475-7799.1119. ISSN 2475-7799.

- Yang, Shao-yun (2017). Chen, BuYun (ed.). "Changing Clothes in Chang'an". China Review International. 24 (4): 255–266. ISSN 1069-5834. JSTOR 26892132.

- Zhao, Qiwang (2019). "The Origin of Partial Decorations in Gowns of the Northern Qi and Tang Dynasties". 2nd International Conference on Cultures, Languages and Literatures, and Arts: 342–349.

- "Woman's Costume in the Tang Dynasty". en.chinaculture.org. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2021-06-30.

- "Woman's Costume in the Tang Dynasty". en.chinaculture.org. p. 1. Archived from the original on 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2021-06-30.

- China : dawn of a golden age, 200-750 AD. James C. Y. Watt, Prudence Oliver Harper, Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2004. p. 311. ISBN 1-58839-126-4. OCLC 55846475.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Zhang, Qizhi (2015). An introduction to Chinese history and culture. Heidelberg. ISBN 978-3-662-46482-3. OCLC 907676443.

- Zhu, Ruixi; 朱瑞熙 (2016). A social history of middle-period China : the Song, Liao, Western Xia and Jin dynasties. Bangwei Zhang, Fusheng Liu, Chongbang Cai, Zengyu Wang, Peter Ditmanson, Bang Qian Zhu (Updated ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom. ISBN 978-1-107-16786-5. OCLC 953576345.

- Tackett, Nicolas (2017). The origins of the Chinese nation : Song China and the forging of an East Asian world order. Cambridge, United Kingdom. ISBN 978-1-107-19677-3. OCLC 991722388.

- Li, Laiyu (2017). "辽代契丹人的服饰——云想衣裳系列" [Clothing of the Khitans in Liao Dynasty - Yunxiang Clothes Series]. www.kaogu.cn. Retrieved 2022-06-16.

- "契丹袍服及辽朝乐舞人物服饰 - 历史文化 - 巴林左旗人民政府网" [Khitan robes and costumes of music and dance figures of the Liao Dynasty]. www.blzq.gov.cn. Bairin Zuoqi People's Government. 2020. Retrieved 2022-06-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Li, Yan (2013). "契丹袍与女真袍" [Khitan robes and Jurchen robes]. zhuangshi. Retrieved 2022-06-16.

- Wang, Guojun (2019). "Absent Presence: Costuming and Identity in the Qing Drama A Ten-Thousand Li Reunion". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 79 (1): 97–130. doi:10.1353/jas.2019.0005. ISSN 1944-6454. S2CID 228163567.

- Su, Wenhao (2019). "Study on the Inheritance and Cultural Creation of Manchu Qipao Culture". Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research. Atlantis Press. 368: 208–211. doi:10.2991/icassee-19.2019.41. ISBN 978-94-6252-837-6. S2CID 213865603.

- "Court Robe - 19th century". www.metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 2021-12-23. Retrieved 2021-12-23.

- Fashion, identity, and power in modern Asia. Kyunghee Pyun, Aida Yuen Wong. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. 2018. p. 116. ISBN 978-3-319-97199-5. OCLC 1059514121. Archived from the original on 2018.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Ju-Ri, Yu; Jeong-Mee, Kim (2006). "A Study on Costume Culture Interchange Resulting from Political Factors". Journal of the Korean Society of Clothing and Textiles. 30 (3): 458–469. ISSN 1225-1151.

- Choi, Eunsoo. "Dallyeong (團領)". Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Culture. Retrieved 2022-06-15.

- Lim, Hyunjoo; Cho, Hyosook (2013). "A Study on the Periodic Characteristics of Wonsam in the Joseon Dynasty". Journal of the Korean Society of Costume. 63 (2): 29–44. doi:10.7233/jksc.2013.63.2.029. ISSN 1229-6880. S2CID 191358407.

- Yarwood, Doreen (2011). Illustrated encyclopedia of world costume. Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications, Inc. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-486-43380-6. OCLC 678535823.

- Traditional Japanese literature : an anthology, beginnings to 1600. Haruo Shirane (Abridged ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. 2012. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-231-50453-9. OCLC 823377029.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - "Dress - Japan". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2022-04-23. Retrieved 2021-04-02.

- "Vietnamese woman revives country's ancient clothes". Tuoi Tre News. 2019-10-08. Archived from the original on 2019-10-08. Retrieved 2021-06-30.

- Nguyen, Hannah (2020-06-14). "Weaving a Realm: Bilingual book introduces Vietnam's costumes from the 15th century". Vietnam Times. Archived from the original on 2020-07-18. Retrieved 2021-07-01.