Orstkhoy

The Orstkhoy,[lower-alpha 1] exonyms: Karabulaks,[lower-alpha 2] Balsu,[5] Baloy[lower-alpha 3] are a historical ethnoterritorial society among the Chechen and Ingush people. Their homeland is in the upper reaches of the Assa and Fortanga rivers in the historical region of Orstkhoy-Mokhk (the Sernovodsky District of the Chechen Republic and the border part of the Achkhoy-Martanovsky District of Chechnya, Russia, modern most of the Sunzhensky District of Ingushetia). In the tradition of the Chechen ethno-hierarchy, it is considered one of the nine historical Chechen tukkhums, in the Ingush tradition as one of the seven historical Ingush shahars.[6][7]

.jpg.webp) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| ? | |

| | ? |

| | ? |

| Languages | |

| Chechen, Ingush | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam | |

General information

Ingush origins

The first descriptions of the Orstkhoys by European authors in the second half of the 18th century identified them predominantly with the Ingush. The first author was J. A. Güldenstädt, who mentions the majority of Orstkhoy villages among other Ingush proper and opposes all of them together to the Chechens.[8] Ten years later, L. L. Shteder, making notes about Karabulaks, gives an almost textbook description of the unique details of typical Ingush vestments, cited by travelers and authors of the late 18th-19th centuries, often replicated on the images of that era and no longer characteristic of any other of the peoples Caucasus.[lower-alpha 4][9] The German scientist Professor Johann Gottlieb Georgi, in his fundamental encyclopedic Description of all the peoples living in the Russian state wrote about Karabulaks stating that, "Before anything they were called Yugush (Ingush), but they call themselves Arshtas",[10] while another German scientist, P. S. Pallas, also states that the Karabulaks specifically come from the Ingush (Ghalghaï).[11]

The German geographer and statistician Georg Hassel, in his geographical description of the Russian Empire and Dshagatai mentioned Orstkhoy as an Ingush tribe and also some of Orstkhoy ancestral villages as Ingush when enlisting the territorial division of the Ingush.[12] Subsequently, S.M. Bronevsky confirmed the identity of the Orstkhoy with the Ingush.[13] Just like Güldenstädt, S. M. Bronevsky also mentioned many Orstkhoy ancestral villages as Ingush in 1823.[14] General Staff I.I. Nordenstamm in his "Brief Military statistical description" compiled from information collected during the expedition in 1832 stated that "the Kara-Bulakh language is similar to the Galash dialect, and the latter is similar to the Galgai and Kist dialects."[15] Platon Zubov[16] and Nikolay Danilevsky[17] stated that the Kists, Ingush and Karabulaks all speak the same language. Nikolay Danilevsky also noted that the Chechen dialect differed from the root language.[17]

In 1842, Nazranians and part of Karabulaks made an appeal to the Russian administration where they called themselves "Ingush people".[18]

In the Russian Empire, on the basis of scientific, statistical and ethnographic data, the Orstkhoy were officially classified as Ingush alongside Galashians, Nazranians and other Ingush societies.[lower-alpha 5] In "Overview of the political state of the Caucasus" in 1840[19] as well as in the "Military Statistical Review of the Russian Empire" in 1851, the Orstkhoy are indicated as Ingush.[20] The Orstkhoy were perceived as Ingush by Imperial Russia, as well as in the Imamate of Imam Shamil.[lower-alpha 6]

I. Ivanov, in his article "Chechnya" published in the Moskvityanin magazine, wrote that Chechnya borders on the west with the Ingush tribes Tsori, Galgai, Galash and Karabulak.[22] The Czech-German biologist and botanist Friedrich Kolenati in his work about the Caucasians, wrote about the Orstkhoy as an Ingush tribe alongside Galashians, Kists and others.[23] Adolf Berge in his work "Chechnya and Chechens" gave the following nomenclature of the Ingush: Nazranians, Karabulaks, Galashians, Dzherakh, Kists[lower-alpha 7] Galgai, Tsorins and Akkins.[24][25][26][27] V. A. Volkonsky stated that the Ingush people consist of societies to which he added Orstkhoy and one of the subgroups of Orstkhoy – Merzhoy.[28] A. Rzhevusky in his work "Tertsy" wrote about Karabulaks and Galashians as the restless and militant Ingush societies.[29] According to V. Chudinov, the Karabulaks, Galashians and Alkhons are Ingush who belong to the Arshtkhoy tribe.[30] According to Vasily Potto, Nazranians and Orstkhoy are Ingush societies who once formed one rather a significant and powerful tribe.[31] Russian Count and Minister of War Dmitry Milyutin wrote in his memorials that the Orstkhoy are Ingush who made up part of the Ingush population of the Vladikavkazsky okrug.[32]

Later in the 20th-21th centuries, the Orstkhoy as one of the Ingush societies were indicated by I. Pantyukhov,[33] G. K. Martirosian,[34] E. I. Krupnov[35][36] and O. S. Pavlova.[37]

In Soviet times, Orstkhoy were also officially included in the Ingush, as reflected on their passports.[lower-alpha 8] In Great Soviet Encyclopedia, Orstkhoy are indicated as Ingush.[38] In the scientific community in the second half of the 20th to the early 21st century, the ethnicity of the Orstkhoy is defined as one of the Ingush societies.[lower-alpha 9] The Soviet historian and ethnographer E.I Krupnov in 1971 wrote in his book "Medieval Ingushetia" that the remaining Karabulaks (Orstkhoy) who don't consider themselves Chechens live in Ingushetia in villages such as Arshty, Dattykh, Bamut, Sagopshi.[36]

In the censuses conducted before the Deportation, the vast majority of population of the tribal villages Sagopshi, Dattykh, Alkun, Sarali Opiev, Bamut, Gandalbos was Ingush.[lower-alpha 10]

18th century

The first descriptions of the Orstkhoys by European authors in the second half of the 18th century also identified them with the Chechens. The first author was the German cartographer and printmaker Jacob von Staehlin who in his work "Geographical menology for 1772" included the Karabulaks (Orstkhoy), Chechens, Atakhizs and also Tavlins in the territory of "Kumytskaya or Sandy land",[47] also referred by him as the "Kumytskaya or Chechen land".[48] J. A. Güldenstädt mentions that Karabulaks speak in a Chechen or Midzheg dialect of the Kistin language and that Chechens are often understood as the whole Kistin nation (in this case Nakh Peoples). In 1781, L.L. Städer, while making notes about the Karabulaks, mentions that out of their neighbors the Chechens are closest to them in language and origin.[9] Johann Gottlieb Georgi also mentions that the Karabulak language consists of Kistin and Chechen dialects."[49]

19th century

Many Russian and European authors noted during the early and late 19th century that the Orstkhoy tribe was part of the Chechen nation, among them Baron R. F. Rozen who in 1830 believed that the Chechens are divided … into societies under the name of Chechens themselves or Mechigiz, Kachkalyks, Mechikovites, Aukhites and Karabulaks (Orstkhoy) …" Nordenstam also remarked in 1834 that "Karabulaki (Orstkhoy), Aukhites and Kachkalyk people speak dialects of the Chechen language".[50] Also of note is Nikolay Danilevsky who in 1846 noted that the Karabulaks are a subgroup of the Chechen nation.[51] Ivanov connected a part of Karabulaks with the "Peaceful Chechens"[52] and Kolenati referred to the land Karabulaks inhabit on as Chechnya.[23] Russian colonels such as Baron Stahl mentioned the Orstkhoy by the Chechen self name "Nakhche" in 1852.[53] The Russian-German general A.P. Berger in 1859 also connected the Chechen self name "Nakhche" to the Orstkhoy:

“Here is the calculation of all the tribes into which it is customary to divide the Chechens. In the strict sense, however, this division has no basis. It is completely unknown to the Chechens themselves. They call themselves Nakhche, i.e. "people" and this refers to the entire people who speak the Chechen language and its dialects. The mentioned names were given to them either from auls, like Tsori, Galgay, Shatoi, etc., or from rivers and mountains, like Michikovtsy and Kachkalyks. It is very likely that sooner or later all or most of the names we have given will disappear and the Chechens will retain one common name.[54]

The military historian A. L. Zisserman, who served 25 years in the Caucasus, also mentions the Karabulaks in his book, stating "All this valley up to the right bank of the Terek River is inhabited…. Karabulaks and Chechens, etc., belonging by language and customs, with insignificant differences and shades, to one Chechen tribe (Nachkhe)."[55] In the Bulletin of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society for 1859, Karabulaki-Orstkhois are noted as Chechens.[56] 19th Century Caucasian military historian V. A. Potto also attributed the Karabulaks to the Chechen people. [57] Historian N. F. Dubrovin in 1871 in his historical work History of war and dominion of Russians in the Caucasus states the following: in addition to these societies, the Chechen tribe is divided into many generations, which are named by Russians by the names of auls, or mountains, or rivers, in the direction of which their auls were located. For example, Karabulaki (Orstkhoevtsy), on a plain irrigated by the rivers Assa, Sunzha, and Fortanga, etc.[58] Several encyclopedias of the late 19th and early 20th centuries attribute the Karabulaks (Orstkhoys) to the Chechen people[59][60][61][62]

In 1862 after the Caucasus war several Orstkhoy villages (Meredzhi, Yalkharoy, Galai and the villages surrounding them) were put into the Ingushskiy Okrug until 1866 when they were ceded to the Argunskiy Okrug due to them belonging to the same nation as the locals (Chechen) and geographically closer to the central governance of the Okrug.[63]

20th century

The Soviet historian and ethnographer E.I Krupnov in 1971 noted in his book "Medieval Ingushetia" that at present time, the Karabulaks (Orstkhoy) are classified more as Chechens than Ingush in the scientific circles, without denying their proximity to the Ingush.[36] Soviet ethnographers like the famous N.G Volkova who interviewed Vainakh people noted in 1973 that Chechen highlanders identify Orstkhoy as "Nokhchi" (self-name of Chechens) but that Chechens living on the Martan river brought them closer to Ingush people. The Ingush however identified Orstkhoy as a separate nation whose language was closer to Chechen. The Orstkhoy themselves according to Volkova identified closer to "Nokhchi" (self-name of Chechens) and saw themselves as one nation with Chechens. The Orstkhoy also said that no one considers them Ingush but that they were written down as Ingush on their passports.[64]

History

Chronology of major events

- 1807 — "Pacification" of the Orstkhoys by Russian troops led by Major General P. G. Likhachev. Military historian V. A. Potto called this act "the last feat of Likhachev's fifteen years of service in the Caucasus".[70]

- 1822 — Ingush and Karabulaks participate in the Uprising of Chechnya together with Chechens against Russian Empire.[71]

- 1822 — Ingush and Karabulaks participate in the new Uprising of Chechnya together with Chechens against Russian Empire.[72]

- 1825 — Russian troops made a military expedition to the Orstkhoy settlements along the rivers of Assa and Fortanga.[73]

- 1827 — Another recognition of Russian citizenship by the Orstkhoys. Along with some other North Caucasian peoples, the Orstkhoys swore allegiance to Russia thanks to the actions of the commander of the troops on the Caucasian line, in the Black Sea and Astrakhan (as well as the head of the Caucasus Governorate) - General G. A. Emmanuel, who was rewarded for this accession, made not by force of arms, but smart orders, was granted the Order of St. Alexander Nevsky.[74]

- 1858 — the Orstkhoys, together with the Nazranians, the Galashians and the inhabitants of the Tarskaya Valley, took part in one of the episodes of the Great Caucasian War - the Nazran uprising, which ended unsuccessfully.[73]

- 1865 — (after the end of the war) — several thousand Orstkhoys were evicted/resettled in Turkey , in particular 1366 families,[lower-alpha 11] in fact, the main part of them - in the ESBE it was even reported that the Orstkhoys/Karabulaks are a tribe that “completely moved to Turkey”.[76]

Notes

- Self-names of Orstkhoy: Arshte, Arshtkhoy, Ärshtkhoy, Arstkhoy, Oarstkhoy, Orstkhoy, Ershtkhoy.

• Ingush: Орстхой,[1][2] Арштхой (Оарштахой),[3] Оарштхой, Оарстхой[4]

• Chechen: Орстхой - Also sometimes in Russian sources of XVIII-XIX centuries, the Plains Akkins/ Aukhs were called Karabulaks (in pre-reform orthography, ethnonyms were indicated with a capital letter - Karabulaki). Probably, the extension of the name Karabulaks to the plains Akkins was due to the fact that the Orstkhoy/Karabulaks made up a significant part of the settlers who participated in the formation of this ethnic group.

- Also, part of the Nokhchmakhkakhois/Ichkerians called the mountain Akkins and Yalkhoroy Baloy.

- For example Peter Simon Pallas, Julius Klaproth and others.

- Генко 1930, p. 685 referring to the “Statement of the peoples living between the Black and Caspian Seas in the area subject to Russia with the meaning of the population of these tribes, the degree of their obedience to the government and the form of government”, 1833 (RGVIA F. 13 454., Op. 12., D 70), an extract from Statement... was published in the appendix to the Military Statistical Description of the Terek Region by G. N. Kazbek, part I, Tiflis, 1888, p. 4.

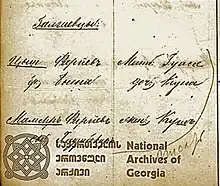

- According to information from the Arabic "Map of Shamil's possessions", stored in the National Archives of Georgia and its Russian translation of the same year with "Explanation to the districts of Dagestan" for the retinue of His Imperial Majesty, entitled "Dagestan's Imam and Warrior Shamil". The map was compiled by a Chechen naib Yusuf Safarov from Aldy on Shamil's orders specifically for sultan Abdul-majid I (1839-1861), and sent to Istanbul with the Ottoman officer Hadji Ismail, who arrived from him to Shamil, but was intercepted on the way back in Georgia. In a special table, twice entitled "Explanation of how many districts in Dagestan are on this map and into how many parts Dagestan is divided", there is a special column "Ingush division (iklim)", under which are named "Mardzhï", "Galgaï", "Inkush", "Kalash", "Karabulaq". Total "5".[21]

- Including the Distant Kists and Nearby Kists.

- Волкова 1973, p. 170; Шнирельман 2006, pp. 209–210 (referring to Волкова 1973, pp. 162, 170–172).

- For example Крупнов 1971, pp. 119, 152, 174; Павлова 2012, pp. 56, 83.

-

• In 1874 the population of Sagopshi consisted entirely of Ingush.[39] In 1890 the population of Sagopshi consisted entirely of Ingush.[40] In 1926 the population of Sagopshi was majority Ingush.[41]

• In 1890 the population of Alkun consisted entirely of Ingush.[42] In 1914 the population of Alkun consisted entirely of Ingush.[43] In 1926 the population of Alkun consisted predominantly of Ingush.[44]

• In 1890 the population of Sarali Opieva consisted entirely of Ingush.[42] In 1914 the population of Sarali Opieva consisted entirely of Ingush.[43]

• In 1890 the population of Dattykh consisted entirely of Ingush.[45] In 1926 the population of Dattykh consisted predominantly of Ingush.[46]

• In 1926 the population of Gandalbos consisted entirely of Ingush.[46]

• In 1926 the population of Bamut consisted predominantly of Ingush.[46] - The Ingush historian N. D. Kodzoev indicated the number of settlers as following: "about 3-5 thousand Ingush (mostly Orstkhoy)".[75][73]

References

- Куркиев 2005, p. 330.

- Барахоева, Кодзоев & Хайров 2016, p. 56.

- Мальсагов 1963, p. 142.

- Кодзоев 2021, p. 184.

- Гюльденштедт 2002, p. 243.

- Anchabadze 2001, p. 29.

- Павлова 2012, pp. 56, 83.

- Гюльденштедт 2002, pp. 238, 241–242.

- Штедер 2010, pp. 210–211.

- Георги 1799, p. 62 (84 as PDF).

- Паллас 1996, p. 248.

- Hassel 1821, pp. 724–725.

- Броневскій 1823, pp. 153, 156, 169

"Кисты сами себя называют попеременно Кисты, Галга, Ингуши, и одно названiе вместо другаго употребляютъ."

"...следовательно можно было бы разделить Кистинскую область на две части: то есть на обитаемую Кистами в теснейшемъ смысле, подъ именемъ коихъ разумеются Ингуши, Карабулаки и прочiе колена, и на область Чеченскую"

"Въ земле Ингушей или Карабулаковъ есть соляной ключъ, изъ подъ горы выходящій, коего разсолъ такъ силенъ, что изъ двухъ меръ разсола выходитъ одна мера соли. Сей ключъ, по сказаніямъ впадаетъ посредствомъ другого ручья въ Фартамъ..."

- Броневскій 1823, p. 166.

- Доклад о границах и территории Ингушетии 2021, p. 88.

- Зубов 1835, p. 169.

- Данилевскій 1846, p. 121.

- Дѣло канцеляріи Кавказскаго комитета по просьбѣ Назрановскаго и части Карабулакскаго обществъ объ оставленіи за ними занимаемыхъ ими земель и о другихъ нуждахъ (РГИА. Ф.1268., Оп.1., д.ЗПб. ЛЛ. 1-8.). p. 5 (as PDF):

"Въ 1810-м году мы Ингушевскій народъ вольный и ни отъ кого независимый поселясь около урочища Назрана (отъ [котораго] приняли названіе Назрановцевъ) по приглашенію Россійскаго Генералъ Майора Дель Поццо чрезъ посредство почетнѣйшихъ Старшинъ нашихъ рѣшились добровольно и единодушно вступить въ подданство Россійскаго Императора..."

- "Обзор политического состояния Кавказа 1840 года". www.vostlit.info.(ЦГВИА Ф. ВУА, Д.6164, Ч.93, лл. 1-23.):

"V. Племя ингуш: 1) Назрановцы, 2) Галаши, 3) Карабулаки, 4) Галгаи, 5) Кистины или Кисты Ближние, 6) Джерахи, 7) Цори, 8) Дальние Кисты"

- Кавказский край // Военно-статистическое обозрение Российской империи 1851, p. 137:

"Къ племени Ингушей, занимающихъ плоскость и котловины Кавказских горъ съ правой стороны Терека до верхних частей Аргуна и до теченія Фартанги, принадлежатъ: 1) Назрановцы с Комбулейскимъ обществомъ, 2) Джераховцы, 3) Карабулаки, 4) Цоринцы, 5) Ближніе Кистинцы с небольшимъ обществомъ Малхинцевъ вновь покорившимся, 6) Галгай, 7) Галашевцы, 8) дальніе Кисты…"

- Доклад о границах и территории Ингушетии 2021, pp. 94–95.

- Иванов, И. (1851). "Чечня" [Chechnya]. Москвитянин (in Russian). No. 19–20. Ставрополь: Михаил Погодин.

"...Ингушских племен Цори, Галгай, Галаш и Карабулак..."

- Kolenati 1858, p. 242.

- Мартиросиан 1928, pp. 11–12.

- Крупнов 1939, p. 83.

- Робакидзе 1968, p. 27.

- Крупнов 1971, pp. 36–38.

- Волконскій 1886, p. 54:

"Ингушевское племя состояло изъ слѣдующихъ обществъ: кистинскаго, джераховскаго, назрановскаго, карабулакскаго (впослѣдствіи назвавшегося галашевскимъ), галгаевскаго, цоринскаго, акинскаго и мереджинскаго; всѣ эти общества вмѣстѣ имѣли свыше тридцати тысячъ душъ."

- Ржевускій 1888, p. 72.

- Чудинов 1889, pp. 82–83

"...а всѣ остальные народы были кистинскаго племени и говорили на кистинскомъ, т. е. ингушевскомъ языкѣ. Изъ нихъ карабулаки, галашевцы и алхонцы принадлежали къ колѣну арштхоевъ и жили по сосѣдству съ чеченцами."

- Утвержденіе русскаго владычества на Кавказѣ 1904, pp. 243–244.

- Милютин 1919, p. 277.

- Робакидзе 1968, p. 28.

- Мартиросиан 1928, p. 11.

- Крупнов 1939, p. 90.

- Крупнов 1971, p. 36.

- Павлова 2012, p. 34.

- Большая советская энциклопедия 1937, p. 31 (PDF).

- Терская область. Список населённых мест по сведениям 1874 года 1878, p. 28 (PDF).

- Списокъ населенныхъ мѣстъ Терской области: По свѣдѣніям къ 1-му января 1883 года 1885, p. 21.

- Северо-Кавказское кравое статистическое управление (1929). Поселенные итоги переписи 1926 года по Северо-Кавказскому краю [Settled results of the 1926 census in the North Caucasus region] (in Russian). Ростов-на-Дону: Отдел переписи. p. 407.

- Статистическиія таблицы населенныхъ мѣстъ Терской области 1890, p. 66.

- Списокъ населенныхъ мѣстъ Терской области: (По даннымъ къ 1-му іюля 1914 года) 1915, p. 346–347.

- Северо-Кавказское кравое статистическое управление (1929). Поселенные итоги переписи 1926 года по Северо-Кавказскому краю [Settled results of the 1926 census in the North Caucasus region] (in Russian). Ростов-на-Дону: Отдел переписи. p. 407.

- Статистическиія таблицы населенныхъ мѣстъ Терской области 1890, p. 58.

- Северо-Кавказское кравое статистическое управление (1929). Поселенные итоги переписи 1926 года по Северо-Кавказскому краю [Settled results of the 1926 census in the North Caucasus region] (in Russian). Ростов-на-Дону: Отдел переписи. p. 405.

- Штелин 1771, p. 47 (PDF).

- Штелин 1771, pp. 71, 74–75 (PDF).

- Георги 1799, p. 62(84 as PDF).

- Elmurzaev, 1993, p. 7.

- Данилевскій 1846, p. 133.

- https://www.vostlit.info/Texts/Dokumenty/Kavkaz/XIX/1840-1860/Ivanov_I/text1.htm

- https://www.vostlit.info/Texts/Dokumenty/Kavkaz/XIX/1840-1860/Stahl_K_F/text1.htm

- "Berzhe A.P., Chechnya and Chechens, Tiflis, 1859. p. 79, 81, 83". Archived from the original on 2019-06-21. Retrieved 2023-02-01.

- Zisserman A. L. — Twenty-five years in the Caucasus. (1842—1867). Volume 2. p. — 432. St. Petersburg. 1879.

- "Bulletin of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society. 1859. Part 27. p. — 109". Archived from the original on 2022-09-30. Retrieved 2023-02-01.

- "Potto V.A., The Caucasian War in separate essays, episodes, legends and biographies, Vol. 2, St. Petersburg, 1887. p. 63, 64". Archived from the original on 2022-07-11. Retrieved 2023-02-01.

- Dubrovin has 1871, 368

- "Человек - Чугуевский полк". Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary: In 86 Volumes (82 Volumes and 4 Additional Volumes). St. Petersburg. 1890–1907.

- Encyclopedia of military and naval sciences Archived 2022-09-29 at the Wayback Machine: in 8 volumes / Ed. G. A. Leera. — St. Petersburg: Type. V. Bezobrazov and Co., 1889. — T. 4: Cabal — Lyakhovo. — p. 51.

- Chechens // Garnet Encyclopedic Dictionary: In 58 volumes. — M., 1910—1948.

- Geographical and Statistical Dictionary of the Russian Empire, T. 5. — St. Petersburg, 1885, p.-698.

- https://viewer.rusneb.ru/ru/000200_000018_RU_NLR_BIBL_A_012304072?page=3&rotate=0&theme=white

- Волкова 1973, pp. 170–172.

- "Statistical tables of populated areas of the Terek region / ed. Tersk. stat. com. ed. Evg. Maksimov. — Vladikavkaz, 1890—1891. — 7 t. p. 60". Archived from the original on 2019-05-22. Retrieved 2023-02-01.

- "Settled results of the 1926 census in the North Caucasus region — Don State Public". Archived from the original on 2021-10-20. Retrieved 2023-02-01.

- https://viewer.rusneb.ru/ru/000200_000018_v19_rc_1224684?page=33&rotate=0&theme=white

- https://viewer.rusneb.ru/ru/000200_000018_v19_rc_1519880?page=64&rotate=0&theme=white

- http://elib.shpl.ru/ru/nodes/46057-spisok-naselennyh-mest-terskoy-oblasti-po-dannym-k-1-mu-iyulya-1914-goda-vladikavkaz-1915#mode/inspect/page/175/zoom/9

- Потто В. А. С древнейших времён до Ермолова // Каваказская война. — Ставрополь: «Кавказский край», 1994. — Т. 1. — p. 623.

- Утвержденіе русскаго владычества на Кавказѣ 1904, p. 304.

- Утвержденіе русскаго владычества на Кавказѣ 1904, p. 339.

- Кодзоев 2002.

- Эммануэль Георгий Арсеньевич // Большая Биографическая Энциклопедия. — СПб.: тип. Главного Упр. Уделов, 1912.

- Базоркин 1965, p. 155.

- "Чеченцы". Archived from the original on 2023-03-11. Retrieved 2023-03-11. Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона: в 86 т. (82 т. и 4 доп.). — СПб., 1890—1907.

Bibliography

- Куркиев, А. С. (2005). Мургустов, М. С.; Ахриева, М. С.; Гагиев, К. А.; Куркиева, С. Х.; Султыгова, З. Н. (eds.). Ингушско-русский словарь: 11142 слова [Ingush-Russian dictionary: 11142 words] (in Russian). Магас: Сердало. pp. 1–545. ISBN 5-94452-054-X.

- Барахоева, Н. М.; Кодзоев, Н. Д.; Хайров, Б. А. (2016). Ингушско-русский словарь терминов [Ingush-Russian dictionary of terms] (in Ingush and Russian) (2nd ed.). Нальчик: ООО «Тетраграф». pp. 1–288.

- Мальсагов, З. К. (1963). Оздоева, Ф. (ed.). Грамматика ингушского языка [Grammar of the Ingush language] (in Ingush and Russian). Vol. 5 (2nd ed.). Грозный: Чечено-Ингушское Книжное Издательство. pp. 1–164.

- Кодзоев, Н. Д. (2021). Хайрова, Р. Р. (ed.). Русско-ингушский словарь [Russian-Ingush dictionary] (in Ingush and Russian). Ростов-на-Дону: Типография «Лаки Пак». pp. 1–656. ISBN 978-5-906785-55-8.

- Гюльденштедт, Иоганн Антон (2002). "VI. Провинция Кистия, или Кистетия" [VI. Province of Kistia, or Kistetia]. In Карпов, Ю. Ю. (ed.). Путешествие по Кавказу в 1770-1773 гг. [Journey through the Caucasus in 1770-1773] (field research) (in Russian). Translated by Шафроновской, Т. К. Санкт-Петербург: Петербургское Востоковедение. pp. 238–243. ISBN 5-85803-213-3.

- Anchabadze, George (2001). Vainakhs (The Chechen and Ingush). Tbilisi: Caucasian House. pp. 1–76.

- Павлова, О. С. (2012). Ингушский этнос на современном этапе: черты социально-психологического портрета [The Ingush ethnos at the present stage: features of the socio-psychological portrait] (in Russian). Москва: Форум. pp. 1–384. ISBN 9785911346652. OCLC 798995782.

- Штедер, Л. Л. (2010). "Дневник Путешествия в 1781 году от пограничной крепости Моздок во внутренние области Кавказа" [Diary of a Journey in 1781 from the border fortress of Mozdok to the interior regions of the Caucasus]. Кавказ: европейские дневники XIII—XVIII веков [Caucasus: European Diaries of the 13th-18th Centuries] (in Russian). Translated by Аталиков, В. Нальчик: Издательство В. и М. Котляровых. pp. 202–221.

- Георги, И. Г. (1799). Описание всех обитающих в Российском государстве народов. Их житейских обрядов, обыкновений, одежд, жилищ, упражнений, забав, вероисповеданий и других достопамятностей [Description of all peoples living in the Russian state. Their everyday rituals, habits, clothes, dwellings, exercises, amusements, religions and other monuments] (in Russian). Vol. 2: о народах татарского племени. Санкт-Петербург: Императорская Академия Наук. pp. 1–246.

- Паллас, П. С. (1996). "Путешествие по южным провинциям российской империи в 1793 и 1794 годах" [Journey through the southern provinces of the Russian Empire in 1793 and 1794]. In Аталиков, В. М. (ed.). Наша старина [Our antiquity] (in Russian). Нальчик.

- Hassel, Georg (1821). Vollständige und neueste Erdbeschreibung des Russischen Reichs in Asia, nebst Dshagatai, mit einer Einleitung zur Statistik des Russischen Asiens, nebst des Dshagatischen Reichs [Complete and most recent geography of the Russian Empire in Asia, along with Dshagatai, with an introduction to the statistics of Russian Asia, along with the Dshagatic Empire] (in German). Vol. 12: Vollständiges Handbuch der neuesten Erdbeschreibung. Weimar: Verlag des geographischen Instituts. pp. 1–896.

- Броневскій, С. М. (1823). "Кисты (глава третья)" [Kists (chapter three)]. Новѣйшія географическія и историческія извѣстія о Кавказѣ (часть вторая) [The latest geographical and historical news about the Caucasus (part two)] (PDF) (in Russian). Москва: Типографія С. Селивановскаго. pp. 151–186.

- Зубов, П. П. (1835). Картина Кавказскаго края, принадлежащаго Россіи и сопредѣльныхъ оному земель въ историческомъ, статистическомъ, этнографическомъ, финансовомъ и торговомъ отношеніяхъ [A picture of the Caucasus region belonging to Russia and adjacent lands in historical, statistical, ethnographic, financial and trade relations] (in Russian). Vol. 3. С. Петербургъ: Типографія Конрада Вингебера. pp. 1–272.

- Данилевскій, Николай (1846). Кавказъ и его горскіе жители въ нынѣшнем ихъ положеніи [The Caucasus and its mountain inhabitants in their current position] (in Russian). Москва: Университетская типографія. pp. 1–197.

- "Кавказский край" [Caucasian territory]. Военно-статистическое обозрение Российской империи: издаваемое по высочайшему повелению при 1-м отделении Департамента Генерального штаба [Military Statistical Review of the Russian Empire: published by the highest command at the 1st branch of the Department of the General Staff] (in Russian). Vol. 16. Part 1. СПб.: Типография Департамента Генерального штаба. 1851. pp. 1–274.

- Генко, А. Н. (1930). "Из культурного прошлого ингушей" [From the cultural past of the Ingush]. Записки коллегии востоковедов при Азиатском музее [Notes of the College of Orientalists at the Asian Museum] (in Russian). Vol. 5. Ленинград: Издательство Академии наук СССР. pp. 681–761.

- Общенациональная Комиссия по рассмотрению вопросов, связанных с определением территории и границ Ингушетии (2021). Всемирный конгресс ингушского народа (ed.). Доклад о границах и территории Ингушетии (общие положения) [Report on the borders and territory of Ingushetia (general provisions)] (archival documents, maps, illustrations) (in Russian). Назрань. pp. 1–175.

- Чудинов, В. (1889). "Окончательное покореніе осетинъ" [The final conquest of the Ossetians]. In Чернявскій, И. С. (ed.). Кавказскій сборникъ [Caucasian Collection] (in Russian). Vol. 13. Тифлисъ: Типографія Окружнаго штаба Кавказскаго военнаго округа. pp. 1–122.

- Kolenati, Friedrich (1858). Die Bereisung Hocharmeniens und Elisabethopols, der Schekinschen Provinzund des Kasbek im Central-Kaukasus [Traveling through High Armenia and Elizabethopol, the Shekin Province and Kazbek in the Central Caucasus] (in German). Dresden: Yerlagsbuchhandlung von Rudolf Kuntze. pp. 1–289.

- Мартиросиан, Г. К. (1928). Нагорная Ингушия [Upland Ingushiya] (in Russian). Владикавказ: Государственная типография Автономной Области Ингушии. pp. 1–153.

- Крупнов, Е. И. (1939). "К истории Ингушии" [To the history of Ingushiya]. Вестник древней истории (in Russian). Москва (2 (7)): 77–90.

- Робакидзе, А. И., ed. (1968). Кавказский этнографический сборник. Очерки этнографии Горной Ингушетии [Caucasian ethnographic collection. Essays on the ethnography of Mountainous Ingushetia] (in Russian). Vol. 2. Тбилиси: Мецниереба. pp. 1–333.

- Крупнов, Е. И. (1971). Средневековая Ингушетия [Medieval Ingushetia] (in Russian). Москва: Наука. pp. 1–211.

- Волконскій, Н. А. (1886). "Война на Восточномъ Кавказѣ съ 1824 по 1834 годы въ связи съ мюридизмомъ" [War in the Eastern Caucasus from 1824 to 1834 in connection with Muridism]. In Чернявскій, И. С. (ed.). Кавказскій сборникъ [Caucasian collection] (in Russian). Vol. 10. Тифлис: Типографія Окружнаго штаба Кавказскаго военнаго округа. pp. 1–224.

- Ржевускій, А. (1888). Терцы. Сборникъ исторических, бытовыхъ и географическо-статистическихъ свѣдѣній о Терскомъ казачьем войскѣ [Tertsy. Collection of historical, everyday, geographical-statistical information about the Terek Cossacks army] (in Russian). Владикавказъ: Типографія Областнаго Правленiя Терской Области. pp. 1–292.

- Милютин, Д. А. (1919). Христіани, Г. Г. (ed.). Воспоминанія. Книга 1, 2, 3 [Memorials. Book 1, 2, 3] (in Russian). Vol. 1. Томскъ: Изданіе военной Академіи. pp. 1–458. ISBN 5998998936.

- Волкова, Н. Г. (1973). Этнонимы и племенные названия Северного Кавказа [Ethnonyms and tribal names of the North Caucasus] (in Russian). Москва: Наука. pp. 1–210.

- Шнирельман, В. А. (2006). Калинин, И. (ed.). Быть Аланами: Интеллектуалы и политика на Северном Кавказе в XX веке [To be Alans: Intellectuals and Politics in the North Caucasus in the 20th Century] (in Russian). Москва: Новое Литературное Обозрение. pp. 1–348. ISBN 5-86793-406-3. ISSN 1813-6583.

- Потто, В. А., ed. (1904). Утвержденіе русскаго владычества на Кавказѣ. Vol. 3: Part 1. Тифлис: Типографія штаба Кавказскаго военного округа. pp. 1–527.

- Шмидт, О. Ю., ed. (1937). Большая советская энциклопедия [Great Soviet Encyclopedia] (in Russian). Vol. 28: Империалистическая война - Интерполяция (1st ed.). Москва: Советская энциклопедия. pp. 1–501.

- Зейдлиц, Н. (1878). Терская область. Список населённых мест по сведениям 1874 года [Terek region. List of populated places according to 1874]. Списки населенных мест Кавказского края (in Russian) (1st ed.). Тифлис: Типография Главного управлении наместника Кавказского. pp. 1–81.

- Терскій Областной Статистическій Комитет (1885). Благовѣщенскій, Н. А. (ed.). Списокъ населенныхъ мѣстъ Терской области: По свѣдѣніям къ 1-му января 1883 года [List of populated areas of the Terek region: According to information on January 1st of 1883] (in Russian). Владикавказъ: Типографія Терскаго Областнаго Правленія. pp. 1–78.

- Терскій Областной Статистическій Комитет (1890). Максимов, Е. (ed.). Сунженскій отдѣл [Sunzhensky Otdel]. Статистическиія таблицы населенныхъ мѣстъ Терской области (in Russian). Vol. 1. Issue 1. Владикавказъ: Типографія Терскаго Областнаго Правленія. pp. 1–85.

- Терскій Областной Статистическій Комитет (1915). Гортинскій, С. П. (ed.). Списокъ населенныхъ мѣстъ Терской области: (По даннымъ къ 1-му іюля 1914 года) [List of populated places in the Terek region: (as of July 1, 1914)] (in Russian). Владикавказъ: Электропечатня Типографія Терскаго Областнаго Правленія. pp. 2, 15–459.

- Штелин, Я. Я. (1771). Географическій мѣсяцословъ на 1772 годъ [Geographical menology for 1772] (in Russian). Санктпетербургъ: Императорская Академія наукъ. pp. 1–96.

- Dubrovin N. F. Chechens (Nakhche) // Book 1 "Caucasus". History of the war and domination of Russians in the Caucasus. - St. Petersburg: in the printing house of the Department of Goods, 1871. - T. I. - 640 p.

- Nadezhdin P.P. Caucasian mountains and highlanders // Nature and people in the Caucasus and beyond the Caucasus. - St. Petersburg: Printing house of V. Demakov, 1869. - p. 109. - 413 p.

- Berzhe A.P. The eviction of the highlanders from the Caucasus // Russian antiquity. - St. Petersburg, 1882. - T. 36. - No. 10−12.

- Yu. M. Elmurzaev. Pages of the history of the Chechen people. - Grozny: Book, 1993. - S. 7 - 8. - 112 p. — ISBN 5-09-002630-0.

- Encyclopedia of military and marine sciences / edited by G.A. Leer. - St. Petersburg: Type. V. Bezobrazov and Comp., 1889. - T. IV. — 659 s

- Encyclopedic Dictionary, Man - Chuguevsky regiment. - St. Petersburg: F. A. Brockhaus (Leipzig), I. A. Efron (St. Petersburg), 1903. - T. XXXVIII.

- Berger A. P. Chechnya and Chechens. - Tiflis: printed from the Highest H.I.V. permission in the printing house of the Main Directorate of the Viceroy of the Caucasus, 1859. - S. I-VII, 1-140. — 140 p. : from ill. and maps.

- Encyclopedic Dictionary / edited by: prof. Yu. S. Gambarov, prof. V. Ya Zheleznov, prof. M. M. Kovalevsky, prof. S. A. Muromtsev, prof. K. A. Timirzyaev. - Moscow: Russian Bibliographic Institute Granat, 1930. - T. 48.

- Tsalikov A. T. The Caucasus and the Volga region. - Moscow: M. Mukhtarov, 1913. - p. 35. - 184 p. - History, Ethnology of individual territories.

- Rittikh A. F. IX // Tribal composition of the contingents of the Russian army and the male population of European Russia. - St. Petersburg: Type. Cartographic institution A. A. Ilyin, 1875. - p. 331. - 352 p.

- Tkachev G. A. Ingush and Chechens in the family of nationalities of the Terek region. - Vladikavkaz: Terek region. board, 1911. - p. 150. - 152 p.

- Кодзоев, Н. Д. (2002). История ингушского народа. Глава 5. Ингушетия В XIX В. § 1. Ингушетия в первой половине XIX в. Основание Назрани [History of the Ingush people. Chapter 5. Ingushetia in the XIX Century § 1. Ingushetia in the first half of the XIX century. Foundation of Nazran] (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2019-07-23.

- Базоркин, М. М. (1965). "Дорога заговора и крови. Посвящается 100-летию выселения вейнахов в Турции" [Road of conspiracy and blood. Dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the eviction of the Vainakhs in Turkey]. История происхождения ингушей [The history of the origin of the Ingush] (in Russian). Орджоникидзе.